Patient Stories

Find your care

Our specialists provide a wide range of treatments, including clinical trial therapies. Call 310-825-9011 to learn more about adult congenital heart disease treatment.

In Your Own Words

This section is all about our patients, and gives a voice to those who have stories or experiences to share. These stories can be anonymous, but publication of individual stories will be at the discretion of the Center's faculty.

Please submit your contribution to Pam Miner, NP at [email protected]

An Excerpt From My Life Story

October 25, 2012

Jacqueline C. Goodyear

I was born in 1964 with Double Outlet Right Ventricle (with hypoplastic left ventricle), Mitral Valve Atresia, Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection, and Pulmonic Stenosis. One of the rarest conditions. So at the ripe old age of five months, I went in for a Blalock-Taussig shunt procedure. Yet, it wasn't a guarantee. The chances of survival were minimal, and the doctor's gave my parents a year at most. They told my mother and father to take me home and enjoy the time they had with me. The years ahead of me were filled with sickness, hospitals, anger, frustration, joy, sorrow, loneliness, abandonment, and so much heartache...no pun intended. My parents divorced when I was eight, and my mother moved us to California shortly after. I loved living near the ocean, but often wondered what it would have been like if we had stayed in Michigan. Yes, my father eventually followed us here to be close to his children. I had three older and one younger sibling, and then when my mother remarried in 1975, the youngest of the clan came along. Out of six children, I was the only one fortunate enough to be born with health issues. Yes at times I did not have the brightest of outlooks on life, but I did my best to stay positive, be active, and believe that god did not hate me, and did this for a reason.

At a time in my life when I should be worrying about getting my driver's license or wondering if someone would ask me to go to the prom...simply living my life as a teenager, I had to go in for my second open-heart surgery. As I reflect on that time now, those things were never what mattered to me anyway. I was more concerned with would I wake up in the morning, would I make it to adulthood, would I ever have children, and would a man ever love me. I went day to day wondering about God and his great plan for me. I searched for a place in this world where I belonged. I was so consumed with the fear of dying...I forgot to live. So when I went in at the age of sixteen for my second open heart surgery I vowed if I made it through, I would start living my life, discover whom I was, and pursue the dreams residing in my soul. Dreams of traveling around the world as I lived my life as a writer, meeting the man I meant to share my life with, and faithfully following the spiritual path of my Native American heritage. Dreams that to some, may seem unrealistic for someone with a heart like mine. My life has never been easy, and even to this day, so many years later, I still battle the teenager inside whom feels she doesn't belong. The never-ending battle of my worth still plays a major role in my life. Yet, with each day, and every breath I take, I honor my spiritual connection to all that is in this moment, I am blessed to realize how lucky I am to have been given this amazing gift of my heart, to live the path I am meant to no matter the circumstances or battles I am forced to face. It took a lot of years to believe with faith, commitment, and the love of the people around you...you've already won the war we know as Congenital Heart Disease.

Hearts to Hearts

October 2, 2012

M.E. Jeffrey

One heart patient to another:

Having a heart condition isn't who we are, but it has played a powerful part in who we have become. I'm going to be honest and admit that I don't feel this way every day. Growing up within the congenital heart groups at UCLA has brought me something like an extended family. These are some of the most supportive professionals around. They feel like a team designed for each patient. We are the reason they are here, and why they invest so much of themselves into being there for us. And one of the most important members of the team is YOU! There is so much happening in this community.

With the Peer Support Program at UCLA, we are able to offer support to fellow patients. We will have a place to get together, and a wonderful way to connect. UCLA adult congenital heart cardiology is not just any other doctor's office in a hospital building, and the Peer support program is only a small piece of that community. There is also the patient to doctors, PA/NP and nurse community. Whether you're in the office for a check-up, a pre-op, a post-op, a "time to figure out what's going on with me" or a "what's going to happen next" session, the folks in the white coats are here for the exact same reason, you and your health.

Communication is very important, but communicating what your heart is doing is often difficult. That's okay! I describe what I feel in ways that make sense to me. I don't know why or what it's doing but I know that however I describe it when they come in we figure it out. If you think you might sound weird or silly, don't worry. Another important thing is to be assertive. My fellow heart patients/friends and I often talk about how we leave feeling that we didn't explain our concerns properly, so our questions weren't completely answered.

Some one told me that they'd been feeling crummy, dizzy, and drained of energy. The doctor adjusted their meds, but they truly felt the medication was the cause and didn't say anything because the doctor seemed rushed and their concern wasn't addressed until after a few visits later. If they had spoken up, they wouldn't have had this issue. Like you, I have felt this way as well. I looked at what I needed to do, because I didn't want to feel crummy any more. I also didn't want to go back and feel silly because I couldn't explain why I was feeling crummy. Being assertive for myself is how a visit to the doctor got questions answered. It took awhile to get comfortable again, but I kept openly communicating, and now I'm happy with the process. Trust the way you feel, and if the way you feel is confusing, let them know that too. Together, you and your team can figure it out, and if you need a moment to collect your thoughts say so because it gives them a moment to go over all you've told them.

I am not saying that coming here will always be sunshine and rainbows, that would just not be true, but I am saying that this is a place where healing can happen on every level and the tiny ones, a smile or a laugh, crying or saying you're frustrated will do a lot of good because these are the things that build the bonds of our team. From pediatrics to adults the UCLA heart center is part of my life as well as yours. We're blessed to be part of this team.

Stay tuned for more information about the Peer Support Opportunities.

Write down 3-4 things that you want and need to talk to them about below (no need to get descriptive be general, for example, weird heartbeats, still feeling tired after waking up, feeling sad, etc.) This will help you if you get overwhelmed or remember something you forgot.

From Patient to Physician: A Personal Journey

By Leigh C. Reardon, MD (RES ’11)

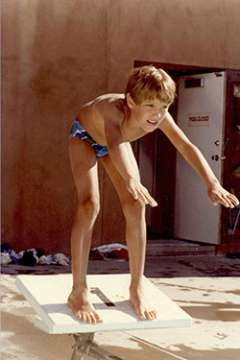

There sometimes comes a moment when you realize that what you’ve always believed to be your greatest weakness is in fact the source of your greatest strength. For me, that awakening began to flicker when I first considered entering medicine as my college years were coming to a close. I had been studying literature and economics, and I figured I would probably end up going to law school or into academia. I was working summers as a lifeguard, and to boost my pay, I decided to become an emergency medical technician (EMT). On the first day of class, the woman sitting next to me noticed the scar peeking out from the top of my shirt, and she began to cry. “You had open-heart surgery,” she said, as she leaned into me. She was right on target; when I was 5 years old, a surgeon cut into my chest to enlarge the narrow pulmonary valve that controlled the flow of blood from my heart to my lungs..

'Hybrid' surgery saves UCLA patient from softball-sized aneurysm

Patricia Crawford had literally been tinged blue all her life because her heart couldn't pump enough oxygenated blood through her body. And that was the least of her worries.

A huge aneurysm the size of a softball in her pulmonary artery was a ticking time bomb. Her heart and liver were failing, too - all adding to the reasons why it was too risky for the 49-year-old to receive the heart-lung transplant she desperately needed to survive. She had been told that she was out of options.

UCLA Congenital Heart Team Heals Hearts of Mother & Newborn

An expecting mother with heart disease is warned the pregnancy is too dangerous, but a team of UCLA specialists guide her through pregnancy, birth and risky open heart surgery on her newborn baby Keyota Cole was born with a bad heart.

The 33-year-old from of Bakersfield, Calif., suffers from a congenital heart disease called Ebstein's malformation of the tricuspid valve, and from abnormal pulmonary veins. She has undergone multiple surgeries over her lifetime, including one to repair a hole in her heart, a valve replacement and the implantation of a pacemaker. Read more

Melody Valve | Transcatheter Replacement

Many children born with congenital heart disease require open-heart surgeries to replace their pulmonary valves with prosthetic valves and conduits. As these children grow, and the valves become dysfunctional, they require as many as five or more open-heart surgeries over the course of their lifetimes to replace poorly functioning valves. A promising new catheter-based approach to replacing these valves may help patients reduce the number of required surgeries, and minimize side effects, by moving the procedure from the operating room to the cardiac-catheterization lab.