UCLA researchers have found that a commonly used chemotherapy drug does not appear to cause cognitive decline following treatment in women with breast cancer.

The study, published online today in JAMA Oncology, refutes concerns raised by research published in 2015 in the same journal. The earlier study, which focused on a small group of women, suggested that a class of drugs called anthracyclines might increase the risk for attention, perception and mood deficits, and other neuropsychological issues, as well as cognitive difficulties, such as memory loss.

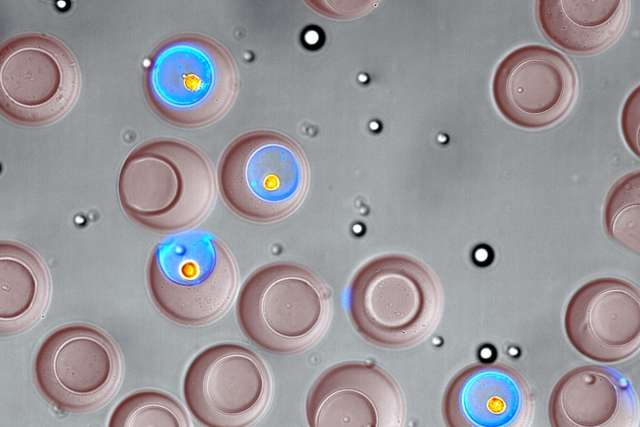

Anthracyclines — well-known examples are doxorubicin and epirubicin — are used to treat many types of breast cancer. But the 2015 research caused widespread uncertainty among physicians and their patients.

In the new paper, UCLA researchers led by Dr. Patricia Ganz and Kathleen Van Dyk analyzed data from a national study involving women with breast cancer. The women, who were tracked for an extended time beginning immediately after their treatment for cancer, received neuropsychological evaluations conducted up to four times, from three months to just under seven years later.

To assess the effects of their treatment, the UCLA team categorized the patients into three groups: those who received anthracycline chemotherapy, those who received chemotherapy with drugs other than anthracyclines and those who received no chemotherapy at all. They then compared the women’s scores on the neuropsychological tests across all four time points.

The scientists found not only that all three groups of women had comparable scores in the areas of memory, processing speed and executive function (such as multitasking and thinking quickly under stress), but also that there were no differences in the women’s cognitive functioning over time, for up to seven years following treatment.

“These results are very exciting because we found no strong evidence linking anthracycline treatment to cognitive decline,” said Ganz, director of cancer prevention and control research at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. “If a physician is recommending anthracycline-based chemotherapy, we do not believe women should be excessively fearful that it is any more likely to cause cognitive difficulties than other types of chemotherapies.”

The scientists plan to continue research focused on understanding the risks and mechanisms for cognitive dysfunction in breast cancer survivors and to investigate promising treatments for women who do experience cognitive decline.

“Experiencing cognitive dysfunction after cancer and its treatment can be extremely disruptive to the lives of breast cancer survivors, and it is critical to better understand what factors, including treatment, might put someone at greater risk for these types of problems,” Van Dyk said. “These results bring us an important step further toward uncovering the influence of treatment on cognitive problems in these women.”

The data analyzed by the UCLA researchers was from a national longitudinal study that examined the effects of endocrine therapy on cognition in breast cancer survivors.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.