Semicircular Canal Dehiscence

Find your care

Put your trust in our internationally recognized brain tumor experts. For more information, connect with a cancer care specialist at 310-825-5111.

Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence (SSCD)

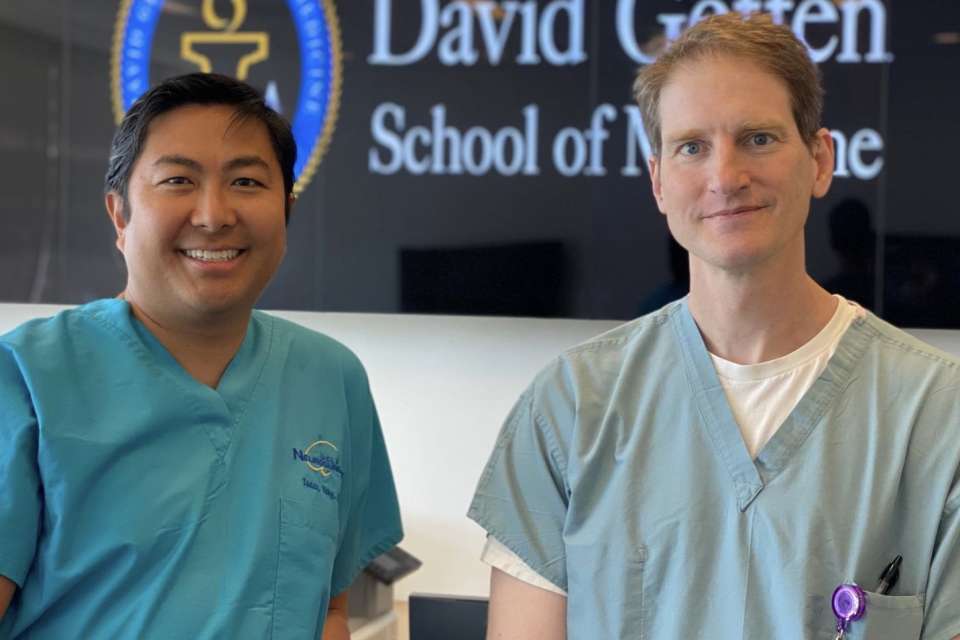

Meet Our Experts

Dr. Isaac Yang, Neurosurgeon, and Dr. Quinton Gopen, otolaryngologist, are the multi-disciplinary team at UCLA that assess and treat patients with Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence (SSCD).

To learn more about research and developments in SSCD, follow Dr. Yang through the social media links below.

Exciting Milestones

April 2023 - Dr. Isaac Yang and Dr. Quinton Gopen Celebrate Their 500th Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence (SSCD) Case

In April 2023, multidisciplinary team Dr. Isaac Yang, Professor of Neurosurgery, and Dr. Quinton Gopen, Associate Professor in the Department of Head and Neck Surgery, completed their 500th Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence (SSCD) case.

September 2024 - Dr. Isaac Yang and Dr. Quinton Gopen Celebrate Their 600th Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence (SSCD) Case

In September 2024, multidisciplinary team Dr. Isaac Yang, Professor of Neurosurgery, and Dr. Quinton Gopen, Associate Professor in the Department of Head and Neck Surgery, completed their 600th Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence (SSCD) case.

What is Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence?

Superior semicircular canal dehiscence (SSCD) is an increasingly recognized neurological condition that is caused by a tiny hole that develops in one of the three canals inside the ear. Healthy individuals have two holes or "mobile windows" in their dense otic capsule bone, but those with SSCD have developed a third hole.The thinning or absence of bone located in the semicircular canal triggers vertigo, hearing loss, disequilibrium, and other vestibular and auditory symptoms. A common clinical symptom of SSCD reported by patients is the abnormal amplification of internal body sounds such as heartbeats and eye movement. Most individuals do not present with any clinical symptoms until they reach middle age, although it has been seen in small children.

Symptoms of Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence

SSCD can present as a bilateral or unilateral syndrome. The thinning or absence of bone in the semicircular canal triggers vertigo, hearing loss, disequilibrium and other balance and auditory symptoms. A common symptom of SSCD is the abnormal amplification of internal body sounds such as heartbeats and eye movements. SSCD is considered a rare disease and the exact cause is unknown. The condition is usually diagnosed in middle age, although it has been seen in small children.

Additional symptoms include:

- Pressure sensitivity

- Sound sensitivity

- Fatigue

- Headache/migraines

- Tinnitus – high pitched ringing in the ears

The symptoms of SSCD can get worse when a patient experiences extended episodes of coughing, sneezing or blowing of the nose. Sometimes hearing one’s own voice can also aggravate SSCD.

Testing

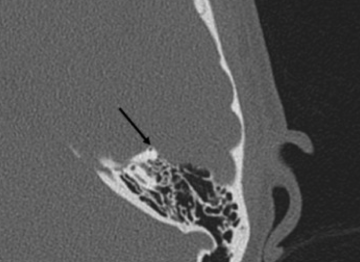

Diagnosis of SSCD is confirmed using a combination of physical examination, physiological testing such as Cervical and Ocular Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential (VEMP) testing; in conjunction with temporal bone high resolution computed tomography (CT) imaging to visualize the defect.

High-resolution computed tomography (CT) scans of the temporal bone is crucial for physicians to diagnose, confirm, and locate SSCD. Sometimes CT scans can overestimate the SSCD when the size is below 3 mm. Thus, it is important to conduct other clinical and neurophysiological tests to compliment the radiological findings.

Vestibular-Evoked Myogenic Potential (VEMP) responses are used by physicians to confirm a suspected presence of SSCD. Patients with SSCD typically have a lower threshold for VEMP response elicitation and larger VEMP amplitudes. VEMP is also important is determining if it is SSCD that is causing conductive hearing loss instead of a true ossicular disease. Patients with a true ossicular disease have test results that are either absent or of elevated thresholds.

Treatments

For patients with mild to no symptoms, it is best to take a conservative approach and simply avoid symptom triggers. Patients with primarily pressure-induced symptoms can have a tympanostomy tube placed, but this is not effective for all patients. Surgical repair of SSCD includes skull-base middle-fossa craniotomy for canal-repair resurfacing, plugging or capping the bony dehiscence. There are always risks associated with surgery, but most patients report a high level of improvement after surgical treatment.

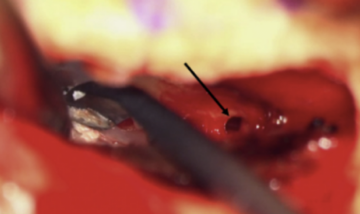

The transmastoid approach and the middle fossa craniotomy are the two main methods of surgical management where the surgeon resurfaces, plugs, or caps the bony dehiscence. Using the middle fossa craniotomy allows the surgeon to directly visualize the bony dehiscence and has been reported to effectively alleviate vestibular issues. Although the dehiscence cannot be visualized through the transmastoid approach, it offers a slightly lower risk of cerebrospinal fluid leak and intracranial complications. Dehiscences can be resurfaced only through the middle fossa craniotomy while plugging can use either approach. However, using the transmastoid approach to plug increases the risk of harming vestibular and cochlear structures, which results in a higher risk of hearing loss. Middle fossa craniotomy resurfacing also has a slightly higher risk of seizure than the transmastoid approach because the temporal lobe needs to be retracted. There are always risks associated with surgery, but most patients report a high level of improvement after surgical treatment.

Research

Dr. Isaac Yang's lab focuses on improving surgical technique and patient outcomes along with exploring the etiological factors which drive the development and progression of SSCD. Working in close collaboration with Dr. Quinton Gopen, the lab's previous work has assessed the efficacy of middle cranial fossa surgical approach, the association between metabolic markers and SSCD symptoms, and differences in outcome between bilateral and unilateral SSCD patients.

Recent Publications

2022

2021

- Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence Revision Surgery Outcomes: A Single Institution's Experience

- Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence Outcomes in a Consecutive Series of 229 Surgical Repairs With Middle Cranial Fossa Craniotomy

2018

Patient Stories

Richard's Story

Out of the blue, Richard Barron, 49, woke up deaf in one ear.

The University of Maine women’s basketball coach was ultra-sensitive to noise--the sound of someone loading the dishwasher was excruciating.

Even stranger, Richard began hearing his bones creak and his eyelids move. Read more >

Karrie's Story

Imagine if every noise your body made echoed loudly in your brain. For nine months, Karrie Aitken, 46, couldn’t tolerate any sound, including her own voice. Each word vibrated in her head like she was trapped inside a barrel. Munching on chips was deafening. But hearing her heartbeat was the worst. Read more >