In a new study of stroke patients, doctors at UCLA Health have identified risk factors that make it more likely a stroke-causing blood clot will break up during removal. When this happens, fragments of the clot can move through the bloodstream and lodge in a smaller artery, causing a new blockage.

“This is a very common problem,” says Jeffrey Saver, a professor of neurology and director of the Comprehensive Stroke and Vascular Neurology Program at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, the senior author of the study which was published on May 20 in the journal Stroke. “We found that about two of every five patients develop these clot fragments, and we’ve now identified important predictors that can help us design better treatments to prevent them in the future,”

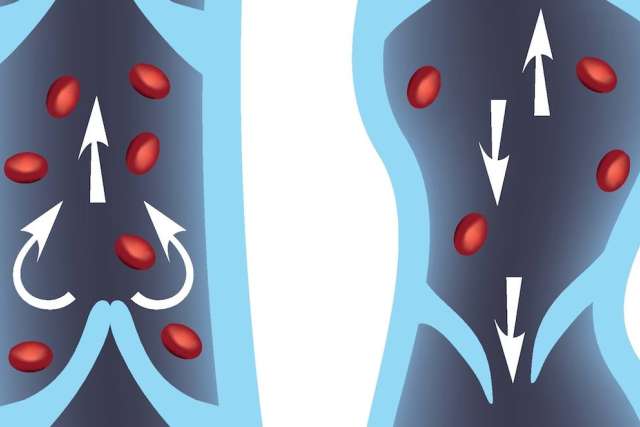

An acute ischemic stroke occurs when a clot stops blood flow through an artery in the brain. Speed is critical when treating these strokes, because more brain cells are damaged with every moment that the blood supply is cut off. While the clot-busting drug tPA can help dissipate some clots, large obstructions need to be pulled out using a mechanical clot-retrieval device.

“This is an approach that was invented here at UCLA, with the first device cleared for use in the United States in 2004 called the Merci coil retriever,” Saver says.

The retriever device is inserted into an artery in the leg, then threaded up to the blocked artery in the brain. Depending on the type of retriever device, the clot is either enmeshed in a wire cage, called a stent, or pulled out by a vacuum aspirator. Because the aspirator pulls the clot by one end, it’s more likely to generate loose fragments. The stent retriever keeps control of the entire clot during its journey through the body, leaving less opportunity for fragments to break free.

“When a patient has risk factors for having a clot that’s likely to fragment, we can use the stent retrievers,” Saver says. “When the patient has features suggesting the clot is not likely to fragment, we can use the faster aspiration device.”

After the clot removal procedure, the patient usually receives medication to prevent additional clotting. But anti-clotting drugs can also lead to dangerous bleeding in a brain that’s already been injured by stroke. There are different classes of anti-clotting drugs, including ones that prevent platelets from forming clots and others that dissolve the protein bonds that hold the clot together. Learning more about the composition of different clot fragments will help researchers design studies to test which drugs work best in which patients.

In the current paper, the researchers identified four key risk factors that increased the chance of a clot fragmenting and a portion lodging in a downstream blood vessel.

First, if blood pressure was low, then there was less force pushing the clot fragments through the vessels, and more chance that a clot fragment could settle in and create a blockage. Second, patients who had been given the clot-dissolving drug tPA ended up with more clot fragments, which makes sense: tPA’s one job is to break up clots.

Third, when the original blockage in the large artery was primarily made up of red blood cells, there was a greater chance of clot fragments taking root than if the original blockage clot was mostly platelets. Red blood cell clots are more likely to break apart and spawn new clot fragments. The fourth risk factor was atrial fibrillation, a type of irregular heartbeat that can increase the risk of clot formation. People with atrial fibrillation are more likely to have red blood cell-rich, fragile clots, which form in the heart.

Saver emphasizes that the risk of clot fragments breaking off and forming a new blockage is not a reason to avoid mechanical clot removal for stroke.

“You’re usually much better off if you have the big artery opened, even if you have a smaller artery blocked afterward as a result of the fragmentation,” Saver says. “Still, we’re constantly trying to understand more about what causes clots to fragment and how to design devices and drugs to avoid that.”

Learn more about UCLA’s Comprehensive Stroke and Vascular Neurology Program.

Caroline Seydel is the author of this article.