Vulnerable adults who test positive for coronavirus may be eligible for new treatments at UCLA Health that could reduce illness severity.

Two monoclonal antibody treatments recently granted emergency use authorization by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration were made available to select patients beginning Dec. 10.

“This is incredibly significant to our county, to California, to our patients and to the community that we have the ability to offer this therapy,” says Quanna Batiste-Brown, DNP, RN, chief nursing officer of ambulatory care for UCLA Health. “It provides hope for patients who are symptomatic COVID patients, who are positive, but they’re not sick enough to be hospitalized.”

“These are the first medications we have for outpatient use,” adds Annabelle De St. Maurice, MD, MPH, UCLA Health’s co-chief infection prevention officer. “That’s the big difference from other medications we’ve used to treat COVID-19.”

The new treatments, which are administered by IV infusion, show promise at reducing hospitalization rates among particularly vulnerable adults, such as those older than 65 and people with severe obesity or other chronic health conditions, says Tara Vijayan, MD, MPH, medical director of antimicrobial stewardship at UCLA Health. Though studies on these new therapies are ongoing, she says, early data show potential benefit in preventing hospitalization and emergency department visits in those who receive them.

That’s particularly important as coronavirus cases have surged in Southern California and medical centers fill with COVID-19 patients.

“Our biggest challenge right now is hospital capacity,” says Dr. De St. Maurice. “So if we can prevent people from getting hospitalized and having severe disease, then that helps both the patient and also the population at large, because we can devote resources to sicker COVID patients.”

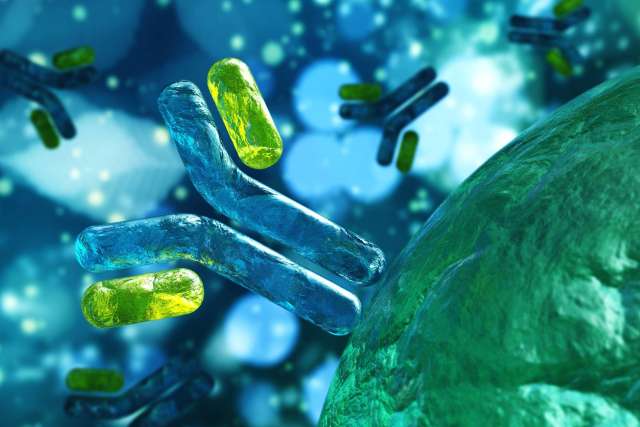

Monoclonal antibodies are lab-developed antibodies that mimic those naturally produced by the immune system in response to infection. The two new therapies, from drug companies Eli Lilly and Regeneron, work by preventing the coronavirus from attaching to cell receptors, such as in lungs, which in turn prevents the virus from replicating and infecting healthy cells.

“These monoclonals are the first available novel therapeutic agents developed specifically for SARS-CoV-2,” the virus that causes COVID-19, says Kara Chew, MD, MS, an infectious disease specialist at UCLA Health. Dr. Chew is one of the lead investigators on a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)-sponsored study, ACTIV-2, to identify safe and effective therapies for COVID-19, including the Eli Lilly monoclonal antibody treatment and a new combination monoclonal antibody therapy developed by Brii Biosciences.

Operation Warp Speed and the Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) program are federal efforts to accelerate the development of therapies and vaccines for COVID-19. They are a partnership between such agencies as the Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health and other federal departments and private firms.

The Eli Lilly and Regeneron monoclonal antibody therapies haven’t received full FDA approval, but emergency use authorization allows for their limited use in populations at high risk for serious illness from COVID-19 who do not meet criteria for hospitalization. “There’s enough data to suggest potential benefits and that the potential benefits could outweigh any unknown safety issues in select high-risk groups,” Dr. Chew says.

People potentially eligible for monoclonal antibody therapy include those 65 and older; those 55 and older with high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease or chronic lung disease; those with severe obesity; and those taking immunosuppressive drugs or who have immunocompromising conditions.

But the window to receive the treatment is short, says Dr. Vijayan. “While not proven, we believe patients are best served by monoclonal antibody therapy within five days of receiving a positive COVID-19 test or exhibiting symptoms.”

The medication is administered through an intravenous infusion and requires a three-hour clinic visit, she says. The infusion takes one hour and patients are monitored for at least an hour afterward.

Side effects may include diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, Dr. Batiste-Brown says, and medications are available for patients who experience those symptoms.

People who fit the population criteria who have recently tested positive for coronavirus should contact their primary care physician to learn more about monoclonal antibody treatment and to see if they might be a candidate. While doses are limited, protocols are in place to ensure equitable distribution for UCLA Health patients of all socioeconomic backgrounds, Dr. Vijayan says.

It’s important to note, however, that the treatment is not a cure for COVID-19.

“It may shorten duration of symptoms, but it does not automatically cure the patient, which is why it’s not a standard of care for all patients who are COVID positive,” says Dr. Batiste-Brown, adding that the new therapy is “a step in the right direction.”

“I think this medication gives us hope,” she says. “It gives us something to treat patients with, something we did not have before.”