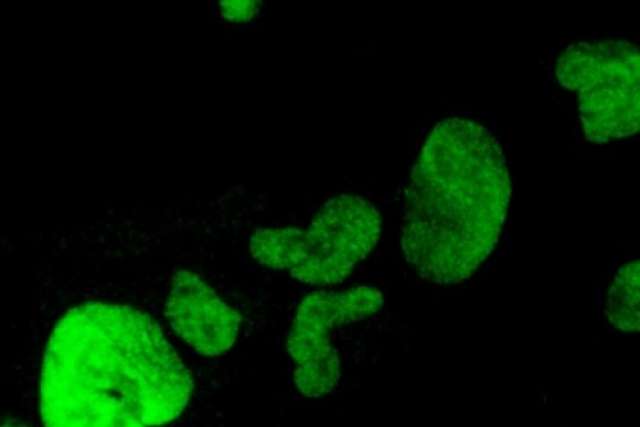

Photo: Germ cell tumors begin in the cells that develop into sperm and eggs. Shown: cells from germ cell tumors

Cancer treatments often come with a trade-off: They beat back the disease, only to leave a host of side effects in its place. Some of those side effects – such as chemotherapy-related infertility – can be permanent and life changing.

Patients with germ cell tumors know this trade-off well. Such tumors, which begin in the cells that develop into sperm and eggs, primarily affect children and young adults, meaning patients who have not yet had children are faced with treatment decisions that could leave them unable to do so.

“The treatments we have are relatively effective in curing germ cell tumors, but they come with a whole host of serious side effects,” says Joanna Gell, a clinical instructor in the division of pediatric hematology and oncology at UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital. “When you’re talking about treating a 15-year-old who wants to live for 70 more years, those side effects can have major impacts on the lives of these patients.”

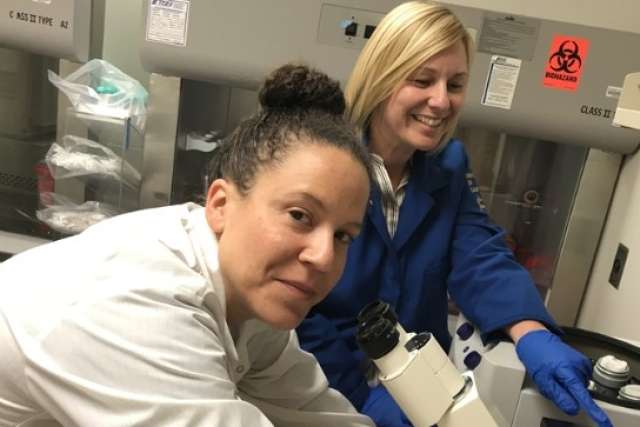

Gell became interested in finding additional treatment options for germ cell tumors after helping care for a teenage girl with a hard-to-treat disease. Through an appointment to a clinical fellowship in the UCLA Eli & Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research’s training program, Gell now works with Amander Clark, a developmental biologist who studies germ cells, to research potential new treatment options.

Germ cell tumors most often develop in the testes and ovaries during embryonic development. However, germ cells that migrate incorrectly during development can lead to tumors in other parts of the body, including the spine, chest and brain.

“What makes this cancer really hard to study is that we think the disease begins in the womb and then remains latent until after birth or in young adults,” says Clark, a professor and chair of molecular cell and developmental biology in the College of Life Sciences at UCLA. “That means we can’t easily isolate or study the very earliest stages of the disease in patients.”

To overcome this hurdle, the pair developed a protocol for coaxing human embryonic stem cells, which can give rise to any cell type in the body, into becoming germ cell tumor cells. These stem cell-derived tumor cells can be examined to provide unprecedented insights into the genetics of the cancer.

The findings from this research, published in Stem Cell Research, could lead to the development of new treatments for germ cell tumors with fewer life-altering side effects.

Clark and Gell are now exploring whether their new protocol could be used to develop personalized therapies for germ cell tumors. They plan to reprogram skin cells from people with germ cell tumors into induced pluripotent stem cells and then coax those cells into becoming embryonic germ cells. This will give researchers the ability to re-create each patient’s tumor cells in the lab.

“By using induced pluripotent stem cells, we’ll now be able to understand the personalized events that occur in these early germ cells that could ultimately contribute to the formation of germ cell tumors,” says Clark. “If we know how the disease starts, we can develop treatments that force it to stop.”