Colin Powell’s death on Oct. 18 from complications of COVID-19 shocked the nation — not only because the former U.S. secretary of state had been such a stalwart figure in American politics, but because he’d been fully vaccinated against the coronavirus.

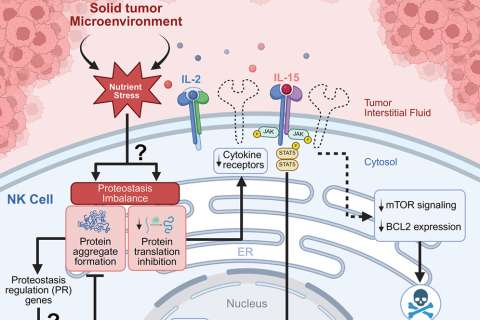

Powell’s vulnerability to the disease was exacerbated by his age and ongoing battle with blood cancer, experts say. The retired four-star general was 84 years old and had been diagnosed with multiple myeloma.

“He had two things that were making it tough for his immune system to respond to the vaccines,” says Paul Adamson, MD, MPH, an infectious disease expert at UCLA Health. “One is older age. For older folks, their immune systems aren’t quite as robust so they are at increased risk for severe infections and it’s a bit harder for their immune systems to mount a response to the vaccines — which is why the CDC and FDA had recommended booster vaccines, really seen as third doses, for older folks. And Colin Powell also had multiple myeloma. That’s a blood cancer that affects your immune cells.”

But it’s a mistake to think Powell’s death means the COVID-19 vaccines are ineffective, experts said.

“Please don’t let the death of an American icon become fodder for anti-vac forces that are putting untold millions in danger,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services spokesman Ian Sams posted on Twitter after Powell’s death. “Vaccines work. They prevent bad outcomes. They (like all vaccines) are not 100%, especially among older people with underlying/complicating health issues.”

Individual immune response to vaccines can vary based on age, illnesses and other factors. But vaccines are still the best way to protect against contagious diseases such as COVID-19, Dr. Adamson says, both individually and collectively.

Vaccines expose the immune system to part of a potential pathogen in a safe way, without an actual infection. This exposure stimulates the production of antibodies and the activation of T-cells, which both work to protect the body from the virus should an actual infection occur.

Vaccines reduce individual infection rates and stem the spread of disease, which offers further protection for the population.

“If we have a lot of virus in the community, if community transmission is high, people are still at risk for getting infected,” Dr. Adamson says. “And, unfortunately, it’s the most vulnerable people in our society that are at highest risk of getting infected and having severe disease, so older folks and people who are immune suppressed. They should get vaccinated on an individual level — that’s the best way to protect themselves — but I also think they would benefit from higher vaccination coverage among others in their communities.”

Dr. Adamson uses a wildfire analogy to illustrate this point: A fireproof suit is much more protective in the face of a few scattered embers than amid a roaring blaze. Similarly, a vaccinated individual experiences greater protection in a community with higher vaccination rates and lower transmission of disease than in one where the virus is spreading unchecked.

“If you have very little virus in the community, then the vaccines will be very protective,” Dr. Adamson says. “But they’re going to appear less protective if there’s a lot of virus in the community. Because when there’s a lot of virus in the community, your chances of getting infected are so much higher. Even then, vaccinated people will still be more protected than those who are unvaccinated.”

Related articles

Study finds people with blood cancer need more protection against COVID-19, even if vaccinated