I WAS 12 OR 13 YEARS OLD WHEN I PICKED UP THE BOOK DEATH BE NOT PROUD. One of my older brothers brought it home from high school to read for a class, but I don’t think he ever did, and it was left lying around the house.

I was an avid reader, so I’d grab pretty much any book that was within my reach. I had no idea what this one was about — the dust jacket gave little clue, other than to say it was “A Memoir” — but from its first pages, this account by John Gunther of the death of his brave and spirited teenage son, Johnny, from a brain tumor had me in its spell.

Even at that young age, I’d already read some pretty weighty books, primarily African American literature. There were heavy, difficult themes in those books. I didn’t know what to expect from this one. It was heavy, to be sure; “death” is right there in the title. But it also was something else — hopeful. I was rivetted by how relentless Johnny’s parents were in their pursuit of different strategies to battle his disease, and by the determination of his doctors to go down every conceivable road that was available in the late 1940s to try to save him. And I felt a close kinship with Johnny. He was 16 years old — just a few years older than me — when he was diagnosed, and through the course of the book, he endured a roller coaster of ups and downs, experiencing progress and setbacks. Yet, he didn’t ever lose hope, and he remained, to the end, courageously optimistic.

I was particularly struck by his deep gratitude for the people who worked so hard to help him. There is one particular line from the book that stands out, a note scribbled across the top of the last letter that Johnny wrote to his mother, Frances, before he died, at the age of 17: “Scientists will save us all.” There is no bitterness or irony in those words; rather, they are an affirmation of his persistent faith that, even though it would not save him, science one day will save others.

It was inspiring to read. At the same time, members of my family were going through serious health issues of their own, and the intersection of Johnny’s journey and the realization that disease can strike people so close to home motivated me further.

And, so, I decided I would be a scientist. I didn’t really know at that time exactly what it was that a scientist does, but I did know what doctors do, and so I told anyone who would listen that I wanted to be an oncologist, because that was the kind of doctors I read about in the book.

Ultimately, however, it was not so much the idea of becoming a clinician who heals others that captured my imagination; what captivated me was the idea of discovering new ways to heal.

Discovery, then, would be my path.

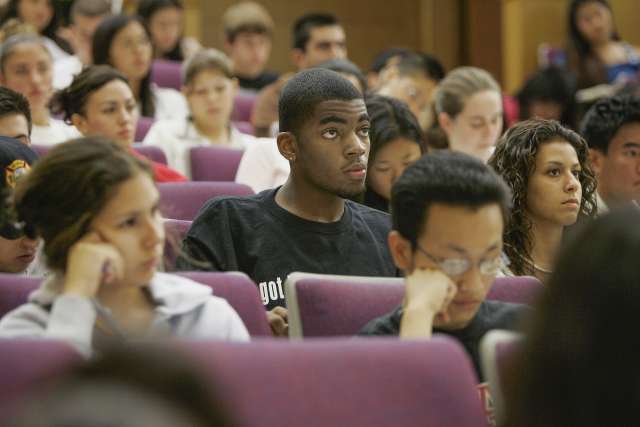

I GREW UP IN COMPTON, CALIFORNIA, a community not known for sending a large percentage of its young people to college, and I attended local schools until high school. I was a good student, and many of my teachers took notice of my interest in math and science, and they became mentors to me. The caring and support shown to me by those strong, Black women helped me to earn admission to a highly competitive magnet high school, and then to UCLA (where I was one of just 96 Black students in my freshman class of some 4,300, but that is a story for another day). I am the middle son among five, and the first person in my family to go to college. It makes me proud that my two younger brothers have followed my example to pursue college degrees.

It has been a rigorous journey, with stops along the way at the National Institutes of Health, UC San Francisco and USC. I have come full circle, back to UCLA, where I conduct research to more fully understand a birth defect called craniosynostosis. It is a condition that causes premature fusion of the sutures — the fibrous joints that connect the bony plates of a baby’s skull — and inhibits proper brain growth. While not life-threatening, it is life-altering, and I hope that our work will not only increase understanding of why the condition occurs but also someday contribute to better treatments.

As I settle into my new lab and begin to pursue my research at UCLA, I think back on the mentors who helped me to get here, and I recognize that now I, too, have a role to play to help other young scientists find their paths. Mentorship, particularly of underrepresented students in the sciences, is incredibly powerful and can be among the most formative experiences anyone can have.

With that as my North Star, my dream is to do my part to uphold Johnny’s expression of faith — “Scientists will save us all” — by not only conducting my own research to, in whatever way I can, defeat illness and death, but also by committing myself to support and guide the next generation of scientists who will make the important discoveries of the future.

That is my dream. It began 20 years ago when I picked up a book.