Laurie Adami has plans to scale a portion of Mt. Everest later this year. But she’d likely tell you that endeavor pales in comparison to the mountains she’s had to climb during her 13-year journey with follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Adami, 61, was one of five UCLA Health patients chosen to participate in the ZUMA-5 CAR T-cell Phase 2, multicenter study of the use of axicabtagene ciloleucel in subjects with relapsed/refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (iNHL).

The immunotherapy, trademarked Yescarta, received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on March 5.

“This is a game-changer,” says Sven de Vos, MD, PhD, director of the UCLA Lymphoma Program and principal investigator for the ZUMA-5 CAR T-cell trial at UCLA Health. “This approval is excellent news because the CAR T-cell outcomes in follicular lymphoma are the best results of any disease treated with CAR T-cells so far. This is something we’ve been waiting for.”

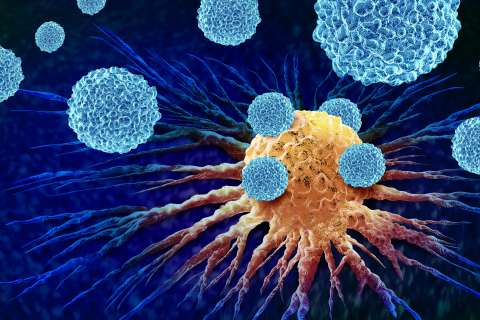

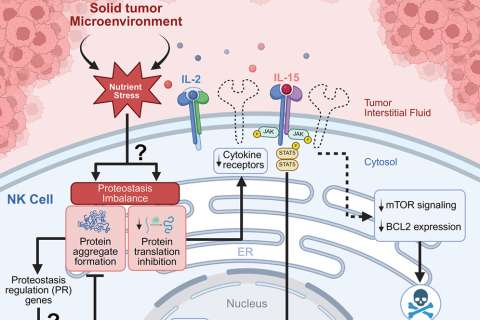

CAR T-cell therapy differs from other iNHL treatments such as chemotherapy or small molecules in that it’s a single-dose infusion that uses the body’s own T-cells, which are genetically modified to add a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) to the surface. When the modified T-cells are reintroduced into the patient’s body, the receptor has the ability to target the T-cell to the lymphoma cells, to latch on to and destroy them.

The ZUMA-5 CAR T-cell therapy is intended for patients who have relapsed at least twice after standard treatments. Adami had relapsed six times when she began the trial in 2018.

Data from the ZUMA-5 study, which included 160 patients at 19 health care centers, show an overall response rate of 95%. Overall response rate is the proportion of patients whose cancer is destroyed or significantly reduced by the therapy.

“These are results seen in lymphomas that had already been treated many times with chemotherapy and other agents,” says Dr. de Vos, chair of the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center Data and Safety Monitoring Board. “To have such a high response rate that late in the course of treatments is astounding.”

The complete response rate is 81% for follicular lymphoma and 75% for marginal zone lymphoma, the two lymphomas tested in the study. Complete response refers to the absence of all detectable cancer after treatment is complete. The median duration of response reported at the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting in June 2020 was 20.8 months.

“Many years of follow-up are needed to know how many patients remain in remission, and to find out if patients have potentially been cured.” Dr. de Vos says.

For Adami, the CAR T-cell therapy came just in time.

A large mass in her abdomen

Adami’s cancer journey began with her diagnosis in April 2006, but her symptoms started more than a year earlier with chronic sinus conditions, dry eye and overwhelming fatigue. Her frustration mounted as her doctors dismissed her symptoms: She was working too hard; she had allergies; the enlarged lymph node in her neck was from a sinus infection; another lump in her abdomen could be a hernia.

The symptoms persisted. “Finally, I was at the end of my rope,” Adami says, “and I decided I had to find a new doctor.” She was referred to an internist near her home, who ordered a PET scan that showed a mass the size of a grapefruit in her abdomen, as well as cancer in her tear duct gland, which was causing her dry eye.

For Adami, who had a son in kindergarten at the time, the diagnosis was a blow. “I felt an overwhelming sense of fear and depression, and disappointment that my body had so let me down,” she recalls.

About 75,000 people in the U.S. are diagnosed each year with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, according to the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS), with follicular the second most common form. This slow-growing cancer affects white blood cells called lymphocytes, which help the body fight infections. The infected cells can travel throughout the body to the organs, bone marrow and lymph nodes, eventually forming tumors.

With treatment, many patients stay disease-free for years, although the cancer often returns, as in Adami’s case, and can turn into a more aggressive type of lymphoma requiring intensive treatment.

Adami started chemotherapy shortly after her diagnosis, thus beginning a recurring cycle of treatment, short-term success and relapse. Subsequent treatments included an HDAC inhibitor, a year of rituxan and bendamustine chemotherapy followed by radioimmunotherapy – a total of 18 cycles of chemotherapy overall.

It wasn’t until her fourth treatment failed, in 2011, that she found Dr. de Vos and the UCLA Lymphoma Program, which is part of the UCLA Division of Hematology and Oncology.

“I was so depressed after my fourth relapse,” Adami recalls. “My son was in fifth grade and I just couldn’t bear the thought of him not having a mom.”

In search of a clinical trial

One afternoon, Adami and a friend began researching clinical trials for iNHL. They emailed eight researchers as far away as Israel and Spain as well as one conducting a trial at UCLA — Dr. de Vos. Within an hour, Dr. de Vos called Adami and told her he had one spot remaining in a phase 1 clinical trial for a P13 kinase inhibitor, but she had to come to his office the next day for a bone marrow biopsy.

That was in 2011, and Adami was in that trial for almost six years. She remained stable until the end of 2016 when her cancer started to grow again. This time, Dr. de Vos put her on a monoclonal antibody called Gazyva. It was Adami’s sixth treatment, and it kept her stable for 10 months before the cancer returned.

“It was incredibly discouraging,” Adami recalls. “Every time I would get the news I would go into this dark place, because each time I would get a new therapy I would have so much optimism. I would say, ‘This is gonna be it.’ My motivating factor was my son, so it was not a choice — I had to stay alive.”

“None of these regimens had put her lymphoma in a lasting complete remission,” Dr. de Vos says. “The lymphoma always came back or was just kept under control for a while.”

Whether it was good fortune or just good timing, the ZUMA-5 CAR T-cell trial launched about the time Adami had run out of options.

“My disease was growing rapidly and I was holding on to hope that this trial would come out soon enough for me to get it,” she says. “The thing that struck me was this treatment was so different — it was going to use my own immune system, and that made so much more sense.”

Dr. de Vos says it’s not surprising that CAR T-cell therapy works well in follicular lymphoma, because follicular lymphoma is one of the few cancers where the immune system already can control the disease to some extent.

“Follicular lymphomas are sensitive and responsive to the control and attack by the immune system and CAR T-cells are one of the strongest ways we can activate the immune system,” he says. “This combination explains why CAR T-cell works so well in follicular lymphomas.”

Nothing short of a miracle

In June 2018, Adami had the four-hour outpatient procedure at UCLA to harvest her T cells so they could be genetically altered in the lab. One month later, she was admitted to Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center to receive her modified CAR T cells.

“It looked like a robot from ‘Star Wars,’” Adami says of the vapor-spewing metal canister that contained dry ice and her modified T cells. “It took about 15 minutes and then you sit back and wait to see what happens. You just wait for the body to do its thing.”

What happened was nothing short of a miracle, Adami says. A scan a month later showed her cancer had completely disappeared. “I had been through so much after 13 years. I was exhausted, and I just didn’t believe it. I was convinced someone was making up this report.”

Today, more than 2½ years later, Adami remains cancer-free. She calls herself “an honorary Bruin” for life and says she’s forever grateful to Dr. de Vos for working with her through many treatments and options. “He had such a command and such a good understanding, and always such a caring attitude,” she says. “He has a special place in my heart.”

Adami’s family is celebrating her good health as well. “It’s a great feeling, a weight off my shoulders,” says Adami’s son, Gus Robertson, now 20. “There’s always the thought in the back of my head it could come back, but the way she’s going right now it’s looking good. She’s feeling good, she’s exercising a lot, she looks good, and that definitely eases my worries.”

In October, Adami and a group of lymphoma research supporters plan to trek to the Mt. Everest base camp, an elevation of 18,000 feet. They and several teammates hope to raise $250,000 for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, which has contributed $40 million to fund CAR T-cell research.

“Planning to climb to Mt. Everest base camp is really a testament to Laurie’s stamina and determination,” Dr. de Vos says. “She is the most actively training participant for the Everest event. It’s really remarkable to see the way she recovered.”

Find out more about UCLA Health’s cancer Community Cancer Care services.

Jennifer Karmarkar is the author of this article.