AS ANYONE WHO FOLLOWS SPORTS KNOWS, a good coach constantly watches what the other team is doing and makes adjustments. The other team, if well coached, also will adjust accordingly. Blindly following a failed strategy doesn’t win games.

Baseball players don’t complain, “Hey, you collapsed the outfield and now you’re sending them deep — which is it?” Basketball players don’t whine, “You told us to crowd the basket; now you’re telling us to shoot from outside — this is confusing.” In volleyball, players don’t grumble, “For the first set we ran the middle of the court and now you want us to set outside — do you even know what you are doing?”

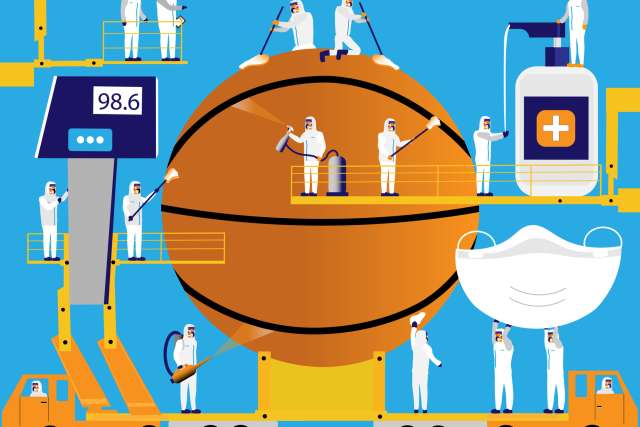

So why are we carping about our public health leaders, especially the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and its director, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, when they are trying to make real-time adjustments, often with incomplete data, to counter the relentlessly changing tactics of an ever-evolving deadly disease?

The CDC undoubtedly made some messaging and decision mistakes — most notably, ending mask requirements too soon — which didn’t help. The agency is also still recovering from the severe loss of credibility it suffered in the last administration. But maybe a deeper problem is that we haven’t really understood the game we are playing or the opponent we face.

A virus doesn’t think up new ways of attacking humans. It doesn’t have a brain. Some doubt that it is even a living thing. It’s an opportunistic collection of parasitic protein molecules and genetic material that invades the cells of living organisms and co-opts that host’s genetic material to replicate. Inside a person, a virus can generate billions of new copies of itself, exact clones and close matches of the original. With so many replications, mutation inevitably occurs, creating new modified versions of the virus. Many of these variants will not be effective at infecting new hosts; they are biochemical screw-ups and will simply die out.

Except, every once in a while a new strain improves, in virus terms, its survivability. The Delta variant of Sars-CoV-2 is such a strain. It has learned to adapt to fluctuations in temperature, humidity and other environmental insults, not unlike a skilled sports team fine-tuning its offense and defense. It is more easily transmitted — scientist believe it is 50% more contagious than the UK strain of COVID that was infecting people in the winter of 2020 — and it now accounts for almost all new cases in the U.S. And it can be more lethal.

Some of these characteristics were already known from laboratory studies and clinical reporting when the CDC loosened its guidelines on mask-wearing. This move occurred last spring, a few months after the roll-out of mass inoculation in the U.S. — when Israel, then Germany and Spain, had just strengthened their mask requirements in the face of Delta.

It was frequently said at the time that the CDC and the administration had to give people something in return for getting vaccinated. If they are still going to have to wear a mask indoors with friends or in the grocery store, many argued, what is their motivation to get vaccinated? Evidently, radically lowering a person’s risk of serious, painful infection or death was not sufficient incentive. Since, at the end of the day, what is going to get us out of the pandemic is widespread (probably over 80%) global vaccination, the CDC may have felt that enticing people to get vaccinated by reducing the mask requirements was worth the risk of more people going around mask-free.

But the problem now is that having loosened mask requirements, it becomes psychologically more difficult for people to re-adopt them, especially while keeping businesses open. Also, specifically absolving the vaccinated of the need to wear masks left many of the unvaccinated feeling a sense of shame when masked in public, if they were even honorable enough to follow the guidelines. From the beginning, some people bristled at the eminently sensible practice of wearing an appropriate mask during a respiratory disease epidemic — and wearing that mask properly, with a good fit covering both nose and mouth. And it has been cynically politicized by those who see an advantage in claiming that wearing masks is somehow launching us on a slippery slope toward the extinction of our basic freedoms.

So, do we need mask mandates for the unvaccinated in most circumstances and for the vaccinated in some? Of course. Mandates are the fairest way to protect everybody, most importantly children under 12 years of age and others who simply cannot currently get vaccinated. When a 4-year-old girl died of COVID-19 this August in a Los Angeles emergency room, it was not her fault. It was a massive failure of those around her, particularly the larger non-compliant society in which, all too briefly, she lived.

During the current college football season, fans crowd stadiums to cheer the skilled competitors and the brilliant moves and countermoves of dueling coaches. Sadly, many of these same fans ignore the carefully considered moves and countermoves recommended by their public health coaches, sabotaging our team’s best chances for success against the virus.

Like a volleyball match, competing against America’s COVID19 pandemic is a five-set game, and we are still in the third set. In the first sets, we did some things well and some things poorly, but in its most recent move, our opponent changed strategies, with devastating effect, gaining a powerful advantage against us. We need to adjust now, as we will again in the future, as we continue to successfully compete against newly emerging COVID clones. Ultimately, our path out of the pandemic is to get many, many millions more Americans vaccinated. Until then, masks are a critical tool.

Let’s understand the opponent we are facing and the game we are playing and recognize that there are different strategies to achieve victory. If Americans get vaccinated and mask up, we may not win on the field, but we will win the competition against an opportunistic and dangerous disease opponent.