UCLA Health is among a small number of U.S. medical centers that will offer recently approved gene therapy treatment for sickle cell disease, a huge breakthrough that may be accessed by very few due to the high expense.

Gary J. Schiller, MD, a hematologist/oncologist and professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, said the new treatments are promising, particularly for younger adults who could experience benefits for longer. But the treatments cost millions of dollars and the potential risk of side effects in the future is unknown.

“These are very interesting,” said Dr. Schiller, a member of the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. “They will definitely not be for everyone. I don’t know how big an impact the two forms will be for the sickle cell community.”

On Dec. 8, 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved two sickle cell disease gene therapies for people 12 and older, describing them as “milestone treatments” for the red blood cell disorder. Roughly 100,000 Americans are living with sickle cell disease.

Casgevy is the first treatment to use CRISPR, the gene-editing technology. The therapy boosts levels of fetal hemoglobin, which the body stops producing in the months after a baby is born. Fetal hemoglobin doesn’t become misshapen or “sickle.” The second, known as Lyfgenia, genetically modifies a person’s red blood cells so they function normally.

For now, Dr. Schiller, director of the Hematological Malignancy/Stem Cell Transplant Program, said UCLA Health will offer Lyfgenia made by Bluebird Bio.

“We will be among the first sites that will be onboarded by the company in the first quarter,” he said.

So far, Casgevy has announced only nine sites that will offer the therapy.

Dr. Schiller said it’s not known yet if insurance will cover the treatments, which cost $2.5 million to $3 million. He noted that prices may also come down over time.

Sickle cell disease is the most common genetic disease in the country and predominantly affects African Americans and a smaller number of Latinos. The inherited red blood cell disorders, which include sickle cell anemia, are the result of abnormal hemoglobin, a protein that delivers oxygen throughout the body.

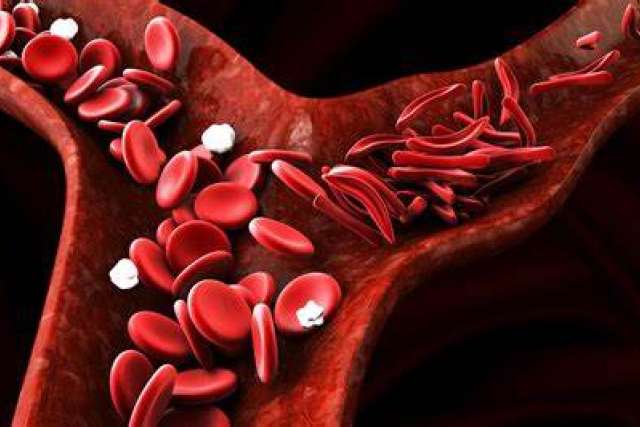

In people with sickle cell disease, red blood cells become hard and sticky, forming the shape of a sickle. The sickle cells die early, resulting in a constant shortage of red blood cells.

“Sickle cell is a devastating disease,” Dr. Schiller said. “When the red cell deforms into a sickle it can form little micro-clots all over the body, obstructing blood flow. That’s painful and that’s dangerous.”

People with sickle cell disease may experience infections, stroke, severe pain and vision loss, resulting in chronic illness, debilitation and premature death.

Existing treatments

Currently, the only curative treatment for sickle cell disease is a bone marrow transplant to replace the blood-forming stem cells that make faulty hemoglobin.

Data shows that most people don’t have a sibling donor who is a match. As a workaround, Dr. Schiller said, “half-match” transplants use a sibling who isn’t a full match. The transplants cost $250,000 to $500,000 and are typically covered by insurance for people with severe disease.

“The only way you can get away with a half-match transplant is by disabling in some way the immune system of the sickle cell patient,” Dr. Schiller said.

That involves giving high-dose chemotherapy before and after the transplant, which carries the risk of organ damage. In rare cases, recipients have developed complications from the donor cells attacking the body of the recipient.

The new gene therapies differ by using a person’s own blood stem cells, eliminating the need for a donor and the potential complications that can arise from a less than perfect match.

By using one’s own bone marrow stem cells, Dr. Schiller said, lower-dose chemotherapy could be used with fewer potential side effects.

“Gene therapy is a very different way of providing for healthy hemoglobin that will not sickle,” he said. “It avoids many of the risks of allogeneic transplant from a donor. There’s no need for matching. There’s no need for the intensive degree of chemotherapy that’s given. And there’s no risk that the immune system will attack the patient’s skin, gut or liver.”

Dr. Schiller said chemotherapy is still needed with the gene modification therapies because the old bone marrow cells need to be destroyed so the transplanted cells can become dominant.

Additionally, he said the FDA will follow patients who receive the new gene therapies to ensure the treatment is safe and that genetic manipulation of the blood cells doesn’t cause leukemia or other types of cancer over time.

“Gene therapy is not a totally new technology but it’s certainly newer and more investigational than half-match donor transplants,” Dr. Schiller said.

How gene therapies work

Casgevy uses the CRISPR gene-editing technology to increase the production of fetal hemoglobin that facilitates oxygen delivery and prevents sickling. After babies are born, the body deactivates the gene responsible for producing fetal hemoglobin. It remains, however, and can be turned back on through gene editing.

Lyfgenia does not edit genes like Casgevy. It works by adding a gene to the person’s blood stem cells so that the body can produce normal hemoglobin. The synthetic gene is delivered to the cells by a harmless virus that then goes away.

“Stem cells taken from the bone marrow or the blood are taken to a laboratory and they are genetically altered to either no longer express sickle hemoglobin or to express fetal hemoglobin, which we normally turn off by the age of 6 months to 2 years,” Dr. Schiller said. “Fetal hemoglobin interrupts sickling.”

For both treatments, people undergo chemotherapy prior to the transplant infusion to kill bone marrow cells so they can be replaced with the genetically modified cells.

“You want to give an advantage to the genetically altered cells so they become the dominant source of blood cell production,” Dr. Schiller said. “They’re the ones that will produce normal hemoglobin.”

The processed cells are infused in the person during a stem cell transplant. If a person has children after undergoing a transplant, the genetically modified cells are not passed on, Dr. Schiller said.

Other sickle cell efforts

Although Dr. Schiller said sickle cell disease is difficult to treat, treatments are improving. He noted three recently approved drugs decrease sickling, although they must be taken for life.

More attention is also being devoted to improving life expectancy and quality of life for people living with sickle cell disease.

In the fall of 2022, Dr. Schiller launched UCLA Health’s sickle cell disease comprehensive center of excellence to offer primary and specialty care throughout the region.

“In Los Angeles County, the life expectancy for adult sickle cell patients is the lowest among all the counties in the U.S.,” he said. “We have not had sufficient outreach to the adult community.”

Nearly 100 patients are now coming to UCLA Health for primary and highly specialized care, as well as an infusion center open daily. Intravenous fluids to prevent dehydration can stop the sickling process and prevent severe pain that can lead to emergency department visits.

Dr. Schiller said he expects the number of patients to grow to 200 in 2024.

“The community has been quite enthusiastic,” he said.

Dr. Schiller said UCLA Health will continue offering gene therapy clinical trials for sickle cell disease so people have a no-cost alternative to the newly approved commercial treatments.

“For individual patients, we’ve seen some very impressive results,” Dr. Schiller said. “Time will tell if those results will be sustained.”

Dr. Schiller said gene therapy could be the best option for someone in their 20s or 30s who is in otherwise good health.

“I think that’s the right patient,” he said. “If you have somebody older, like me, I’d rather be on pills and IVs. I’d probably try the novel medications that have been recently approved.”

In all, he said, doctors and scientists are working hard to improve care since the discovery roughly 70 years ago of the sickle cell mutation.

“There’s a lot of excitement and novel things coming,” Dr. Schiller said. “It’s been a long time coming.”