FINDINGS

UCLA scientists have found that a protein known as NOTCH1 helps ward off inflammation in the walls of blood vessels, preventing atherosclerosis — the narrowing and hardening of arteries that can cause heart attacks and strokes. The new finding, from research conducted on mice, also explains why areas of smooth, fast blood flow are less prone to inflammation: levels of NOTCH1 are higher in these vessels.

BACKGROUND

NOTCH1 was already known to be a key player in the development of blood vessels in embryos, but researchers weren’t sure whether it was also critical to adults’ health. In a 2015 study, Luisa Iruela-Arispe, a UCLA professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology showed that mice on a high-fat diet had reduced levels of NOTCH1.

Researchers also have long known that sections of blood vessels in some areas of the body — where blood flow is slow and disturbed — are more likely to develop inflammation and the fatty plaques associated with atherosclerosis but weren’t sure why.

METHOD

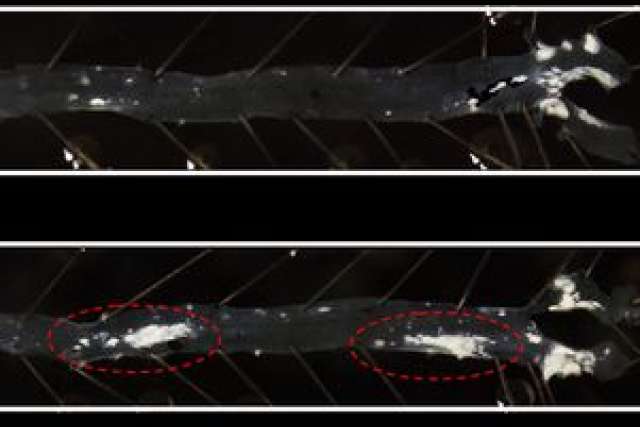

In the new work, Iruela-Arispe and her colleagues mimicked blood flow conditions on a small scale in the lab. Using MRI and high-resolution microscopy, as well as molecular experiments, they observed how NOTCH1 changed under different flow conditions. When the flow was smooth and fast, they found, levels of NOTCH1 were elevated and the protein aligned itself on the end of each cell facing the direction of blood flow.

Using mice that had been genetically modified to lack NOTCH1, the researchers observed that the animals’ blood vessels had gaps between cells and high levels of inflammation. Without NOTCH1, mice with high cholesterol developed atherosclerosis even in areas of smooth, fast blood flow that normally protect against plaques.

IMPACT

High levels of cholesterol are known to predispose people to atherosclerosis and heart disease, but it’s clear that other factors, including genetics, can make a person more or less susceptible to develop the disease. The new link between levels of NOTCH1 in blood vessels, inflammation and atherosclerosis suggests that variations in NOTCH1 between people could affect atherosclerosis risk; those with low levels of NOTCH would be more likely to develop atherosclerosis. More research is needed to determine whether the results seen in mice are the same in humans.

AUTHORS

In addition to Iruela-Arispe, the study’s other authors are Julia Mack, Thiago Mosqueiro, Brian Archer, William Jones, Hannah Sunshine, Guido Faas, Anais Briot, Raquel Aragón, Trent Su, Milagros Romay, Austin McDonald, Cheng-Hsiang Kuo, Carlos Lizama, Timothy Lane, Ann Zovein, Yun Fang, Elizabeth Tarling, Thomas de Aguiar Vallim, Mohamad Navab, Alan Fogelman and Louis Bouchard, all of UCLA.

JOURNAL

The study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications.

FUNDING

The study was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health, including a Ruth L. Kirschstein Institutional National Research Service Award.