The surgeries to remove renal tumors can be difficult, particularly if the cancer is on the posterior side of the kidney and if patients have had previous abdominal surgery, because scar tissue from previous operations usually makes it hard for surgeons to distinguish the normal parts of the body from one another.

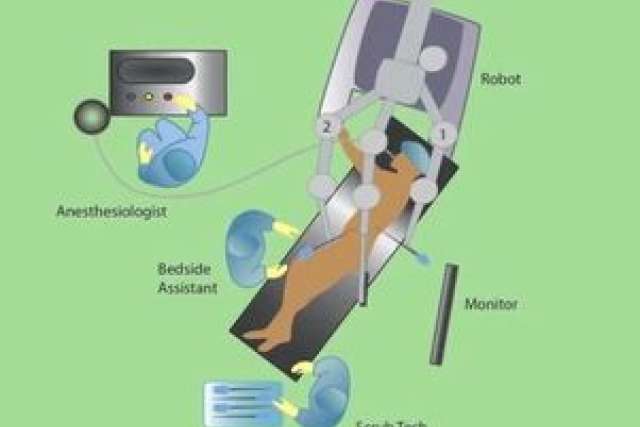

Now, a study led by Dr. Jim Hu and researchers at UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center has shown that a newer surgical technique called robot-assisted retroperitoneoscopic partial nephrectomy is more effective than other current techniques to remove kidney tumors when the masses are located on the back of the kidney or when a patient has had previous abdominal surgery. RARPN is a minimally invasive laparoscopic procedure in which surgeons use precise robotic arms and magnified, high-definition 3-D cameras.

The study, published online in European Urology, was the largest multicenter study to date on this technique. The five-year project reviewed surgeries for 227 patients whose average age was 60, with most between ages 52 and 66.

Currently, most surgical centers use a technique called thermal ablation, in which a heat-producing probe is used to eliminate small renal masses that are otherwise difficult for surgeons to reach. However, patients who undergo thermal ablation are eight times more likely to need CT scans after surgery so doctors can track whether the tumors return — and each additional CT scan exposes the patient to additional harmful radiation.

The study also found significant variation among surgeons using the robot-assisted technique in the amount of time the renal artery, which provides the main blood supply to the kidney, was blocked off during surgery. Depending on the surgeon, this time — known as the warm ischemia time — varied by as much as five minutes, even though all of the surgeons in the study were fellowship-trained, high-volume surgeons. More experienced surgeons were more likely to have shorter warm ischemia times, however. This finding is significant because when blood flow to the kidney is blocked for a longer time during surgery, patients are more likely to suffer complications such as acute kidney failure and long-term chronic kidney disease.

The researchers also found the frequency of surgical complications varied greatly from one surgeon to another, with some recording complication rates that were three times higher than those with the fewest incidents. However, major complications were relatively uncommon: Only three patients in the study required blood transfusions. And cancer recurred in less than 1 percent of the patients in the study.

"These differences in warm ischemia times may be attributable to slight variations in surgical technique," said Hu, who is also director of minimally invasive surgery and holds the Henry Singleton Chair in Robotic and Minimally Invasive Surgery at UCLA. "But we showed center-specific variations in the RARPN approach and we present a video on surgical technique to highlight our approach."

In addition to UCLA, participating centers were the University of Michigan and Swedish Medical Center in Seattle.