Physicians Update

Winter 2022

Included in this issue:

- UCLA Health advances pioneering protocol to enable transplant recipients to thrive without antirejection drugs

- Multidisciplinary care at the heart of UCLA’s adult heart-transplant program

- UCLA program improves outcomes for patients with rare liver cancer

- Vouchers expand reach of living-kidney donations

- UCLA’s lung-transplant program demonstrates success with highest-risk patients

- UCLA Advanced Lung Disease and Lung Transplantation Symposium

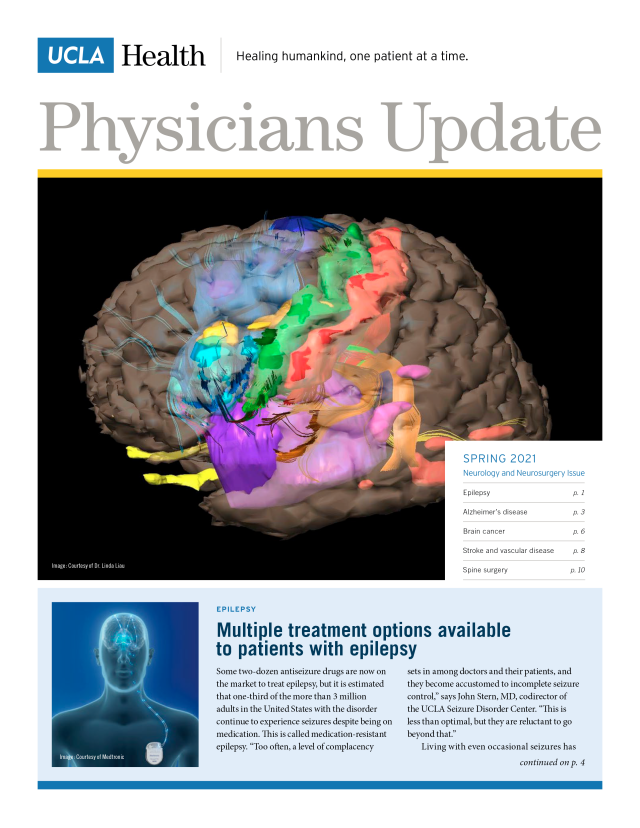

Spring 2021

Included in this issue:

- Multiple treatment options available to patients with epilepsy

- Patients with dementia benefit from treatment in specialized setting

- UCLA Brain Tumor Center takes multidisciplinary approach to attacking glioblastoma

- Comprehensive care following stroke is vital to fullest possible recovery

- Advances in spine surgery open door to relief for a broader spectrum of patients

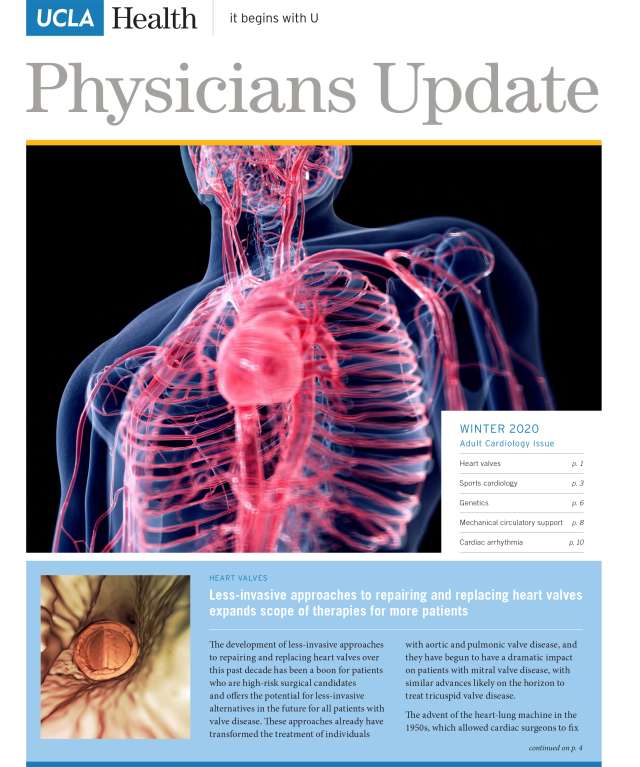

Winter 2020

Included in this issue:

- Less-invasive approaches to repairing and replacing heart valves expands scope of therapies for more patients

- Sports cardiology program tailors care to competitive athletes

- New clinic provides personalized care for patients with inherited or genetic cardiovascular disease

- Mechanical circulatory support has extended life-sustaining options for advanced heart failure patients

- UCLA Cardiac Arrhythmia Center on the forefront of care for patients with most challenging conditions

- UCLA Heart Failure Symposium 2020

Fall 2020

Included in this issue:

- Anesthesiologists have significant role to play in addressing opioid crisis

- Clinical Updates

- Regional anesthesia a boon to patients having joint replacement surgery

- The role of anesthesiologists changes with the times

- New technologies advance pain care for patients with cancer

- Standardized protocols improve outcomes for patients across a broad spectrum of surgical procedures

Fall 2019

Included in this issue:

- Herceptin has saved countless women’s lives and earned UCLA’s Dr. Dennis Slamon the Lasker Award

- Three-drug combination helps curb the growth of a deadly type of skin cancer

- CAR T clinical trial aims at extending the lives of people with most common types of lymphoma and leukemia

- Promise of CAR T-cell therapy may extend beyond current uses

- 3D modeling to prepare for cancer surgeries should become new standard

- Shorter course of radiation therapy effective in treating men with prostate cancer

- Center works to identify children with genetic predisposition to cancer

- Adding ribociclib to hormone therapy extends lives of women with most common breast cancer

- BRCA initiative aims to increase access to testing

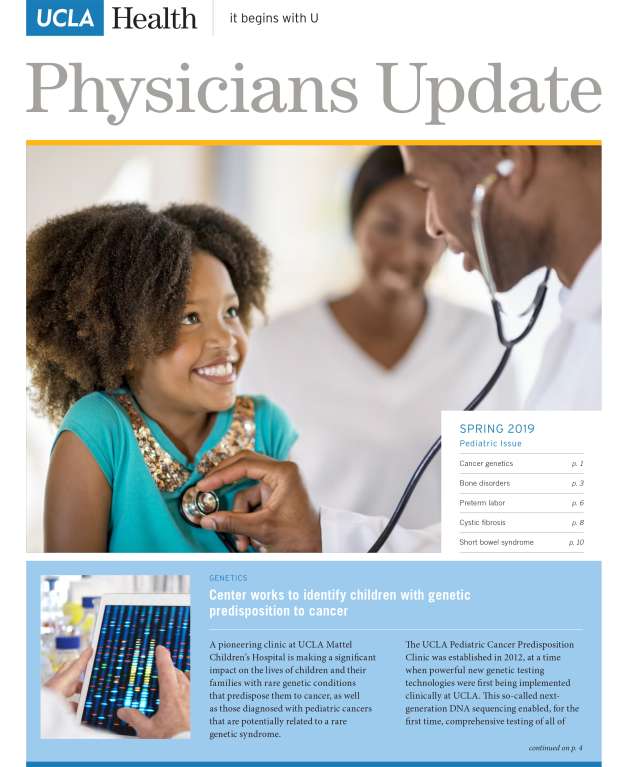

Spring 2019

Included in this issue:

- Center works to identify children with genetic predisposition to cancer

- Specialized center offers evaluation and treatment for perplexing bone disorders

- Drug study aims to reduce risk of preterm labor in women with infection in the womb

- New therapies lead to major advances in treatment of cystic fibrosis

- Children with short bowel syndrome benefit from recent treatment advances

- 4th Annual Pediatric Board Review Course/Board Prep Course

Fall 2018

Included in this issue:

- Advances in facial reanimation are restoring smiles

- Center is a national resource for treating the full range of voice problems, from common to complex

- Researchers explore pharmacological approaches to treat NF2 tumors

- New chair of head and neck surgery looks to the future

- Taking steps toward personalized treatment for patients with head and neck cancers

- Program established to address needs of head and neck cancer survivors

- UCLA center offers management of complex nasal and sinus problems

- Multidisciplinary expertise is best approach to treating balance disorders

Spring 2018

Included in this issue:

- Campaign aims to boost rates of colon cancer screening

- MRI, endoscopy being used to screen patients at elevated risk for pancreatic cancer

- Hands-on, multidisciplinary approach benefits IBD patients

- Addressing diet and nutrition is essential when treating GI disorders

- POEM procedure offers relief for patients with achalasia

- Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases

- UCLA Clinical Updates Spring 2018

Winter 2018

Included in this issue:

- Specialized epilepsy center offers potential remedies to patients with uncontrolled seizures

- New center offers comprehensive care for teens with epilepsy

- Hospital on wheels brings immediate care to stroke patients

- Addressing sleep issues can aid diagnosis of health concerns

- Advances in neurogenetics opens window to rare neurological conditions

- 6th Annual UCLA Review of Clinical Neurology

Winter 2018

Included in this issue:

- Specialized epilepsy center offers potential remedies to patients with uncontrolled seizures

- New center offers comprehensive care for teens with epilepsy

- Hospital on wheels brings immediate care to stroke patients

- Addressing sleep issues can aid diagnosis of health concerns

- Advances in neurogenetics opens window to rare neurological conditions

- 6th Annual UCLA Review of Clinical Neurology

Fall 2017

Included in this issue:

- UCLA Registry Helps Researchers and Physicians to Better Understand Dwarfism

- Synthetic-Cartilage Implant Offers Relief from Great Toe Arthritis

- Tailoring Sarcoma Care to Meet the Needs of the Patient

- New Orthopaedic Surgery Chair Addresses the Challenges Ahead

- Partnership with Lakers Yields Benefits for Everyday Athletes

- 8th Annual UCLA Musculoskeletal Ultrasound Course and Hands-on Workshop

Spring 2017

Included in this issue:

- New Chemo Vector Offers Option for Patients with Difficult to Treat Urologic Cancer

- Immunotherapy Treatment Can Increase Survival for Some Patients with Prostate Cancer

- UCLA Clinic Takes Holistic Approach to Men’s Health

- Comprehensive Approach Needed to Address Recurrent UTIs

- UCLA Radiation Oncology Workshop: Integration of State-of-the-Art Innovations into Clinical Radiation Oncology Practice