Abraham Urias may be a relatively new registered nurse, but he isn’t new to health care. For Urias, who served in the U.S. Army from 2007 to 2014 as a combat medic, his military experience strongly shaped his approach to working with patients in the acute adult psychiatric inpatient unit at the Stewart and Lynda Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital at UCLA Health.

Urias began his military career in Fort Bliss, Texas, then served in Iraq, where he specialized in stabilizing severely wounded patients to prepare them for transport to more comprehensive care facilities. From there, he was transferred to a U.S. Army base in Germany, where he trained pilots to be combat lifesaver certified before their intelligence-gathering missions in Afghanistan.

“It’s basically first aid for a combat environment,” he explained. “They would fly me to different bases to provide a week-long training course to prepare the soldiers on how to care for themselves and their peers, to stabilize them and get them transported to a higher echelon of care.”

By the time Urias arrived at UCLA as an undergraduate transfer student in 2018, he’d already spent considerable time not only as a caregiver, but as a teacher and mentor. But there was an additional aspect that stayed with him: the stigma he observed within the military about substance use and mental health issues among soldiers.

While earning his bachelor’s degree in nursing, Urias rotated through various medical units, including a stint in the psychiatric unit at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance. The camaraderie he saw there reminded him of the tight bonds he’d had in the military. It was this “strong sense of cohesion in helping this population” that cemented Urias’ decision to specialize in psychiatric nursing.

Urias subsequently chose Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital for his three-month immersion (the internship portion of his undergraduate nursing program). Upon graduation, he was hired there in 2022.

Compassion and patience

In addition to more traditional nursing skills such as wound care and medication management, Urias has found that patience and good communication skills are key attributes in a psychiatric care setting.

This includes learning to interpret patients’ more subtle cues, what he calls the “tells,” in lieu of more traditional ways of communicating. This can be small shifts in body language or facial expression indicating that they’re starting to become frustrated, he explained, and learning to recognize these can be key to heading off more extreme reactions.

It’s an example of what Patrick Loney, chief nursing officer at Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital, characterizes as “using communication as a primary therapeutic tool,” which he sees as a key attribute in mental health nursing.

“We practice relationship-based care here at UCLA,” he said. This requires being a thoughtful, good listener, he said – one who’s slow to react to provocation and can be a calming, de-escalating influence.

A ‘disease model’ mindset

When working with psychiatric patients who may be acting out or behaving aggressively, “you have to remember that it’s the disease,” and not intentional behaviors, Urias said. “These behaviors are a symptom of the disease; this isn’t representative of who they are as a person.”

In the same way “you’re not angry at someone for being diagnosed with cancer, you can’t be angry at a person who comes in with a mental illness.”

Sometimes, Urias’ role is to serve as a buffer between his patients and their family members, who may struggle with seeing their loved ones’ mental health issues through this lens. But expecting patients to be able to “snap out of it” isn’t a fruitful approach, he said, nor is expecting them “to respond the way we want them to respond.”

Instead, Urias focuses on bonding with patients and helping them make incremental improvements.

Being a psychiatric nurse requires “being able to operate in shades of gray,” Loney said. “It’s not black and white. And it might be different from patient to patient. We believe that all humans can reach their potential with help, but that’s a little different for everybody.

“These are chronic issues to deal with over time,” he said. “We focus on what healing looks like in the context of a chronic disease state. Unlike, say, a broken bone or an infection, the path to healing might be a little different.”

Helping patients re-establish structure

Urias’ goal in working with patients is to help them be better equipped to pursue their own recovery when they leave Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital than they were when they arrived.

Oftentimes, this is helping them re-establish a sense of structure in their lives – a process Urias likens to basic training in the military, where “you learn to get up in the morning, get dressed, make your bed, report for your meals.”

“When somebody has chronic depression,” he said, “one of the biggest challenges could just be waking up and brushing your teeth, or waking up and taking a shower.”

Helping them bring structure to the morning, so they can take care of themselves, brings him immense satisfaction.

“On the first day, they may be disorganized and unkempt, but when they leave, they’re prepared to participate in a recovery center or group home,” he said. “Because there won’t be someone there to prompt them to do these things – they have to be able to take care of themselves.”

Connecting with patients and their families

The patient population at Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital, which has 74 in-patient beds, is a mix of children (age 4 and older), adolescents, adults and older adults (age 55 and older). Some patients or their caregivers are primarily Spanish-speaking or speak Russian, Farsi or other languages. Nurses such as Urias, who are multilingual, are able to bridge this gap.

Urias, who’s fluent in Spanish, uses it frequently on the job, especially for patients whose primary caregiver or point of contact is a Spanish speaker. He also speaks what he characterizes as “survival level” German and Korean, which he picked up while serving in the military. But even that level of proficiency is enough to make a difference, he said.

“Just the fact that I can introduce myself and say, ‘I’m the one taking care of your child or your family member today’ has disarmed so many people,” he said. “The psychiatric facility can be a scary place – we’re a locked ward. But the fact that I’m able to come in and say, ‘Hi, how are you doing’ in the language that’s familiar to them is comforting.”

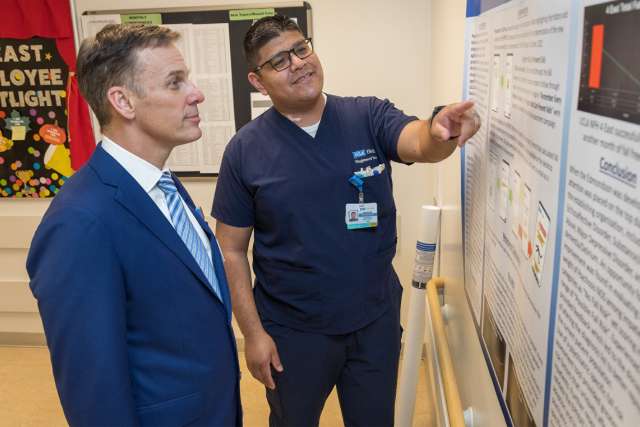

Reducing patient falls

In addition to focusing on incremental improvements with individual patients, Urias has also been working on new safety procedures to help prevent falls in the overall patient population at Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital.

Patient falls are generally thought of as an issue for older patients but are also a significant risk for younger patients in a psychiatric hospital context, he explained. “With our population, we’re dealing with 18- to 44-year-olds who are still having these incidents where they’re falling.”

Because the traditional fall-risk-assessment tool used in hospitals wasn’t adequate for assessing their risk, Urias researched other options that could provide a more accurate assessment for psychiatric patients. This includes noting whether they’re taking psychotropic medications and also flagging the potential increased risk due to multiple medications, such as cardiac medications, which are often prescribed to help reduce anxiety.

Patients’ sleep and eating changes can also increase their fall risk, Urias noted. “With a lot of our patients who are experiencing mania, they don’t feel the need to sleep,” he said. “And they have a decreased appetite. And they’re being hit with multiple medications to try to get them to sleep but still don’t yet have that drive for sleep, so they’re sedated, drowsy and still trying to walk.”

While that type of scenario wouldn’t be flagged by a traditional risk-assessment tool, Urias identified an assessment alternative that was used on a three-month trial basis in the two adult psychiatric units in late 2022. During that time, there were zero patient falls.

Based on these extremely promising early results, a large-scale pilot is being planned, which will allow a formal evaluation to determine if it can be rolled out on a permanent basis.

Urias’ initiative in identifying a specialized fall-risk-assessment tool illustrates Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital’s emphasis on empowering nurses to identify issues and propose solutions, Loney said.

“Because of the time they spend with patients,” he added, “frontline nurses have a unique vantage point and can see opportunities for improvements in a way that few others can.”