Right before he goes to sleep, Jamil Aboulhosn, MD, shuts off his phone, takes a seat at the dining room table, and immerses himself in drawing or painting.

Except when he’s working late at the hospital, this half hour of creative expression has been his nightly ritual for several years.

“It's almost like meditation,” said Dr. Aboulhosn, “where every other thought melts away, and all I'm doing is thinking about shape and form and letting my mind wander.”

Finding the right shade of blue or depicting the play of light provides more than an escape after 14-hour days as director of the Ahmanson/UCLA Adult Congenital Heart Disease Center.

Art has been instrumental in leading Dr. Aboulhosn to specialize in congenital heart conditions. It’s also been a powerful tool for his interactions with patients, for his training as an interventional cardiologist, and for how he teaches others.

“If you can draw something, you will understand it, even if you're not a natural artist,” he explained. “I find it extremely useful when attempting to understand a concept, to actually draw it out.”

If he’s describing an upcoming procedure for a patient and the words don’t seem to click, he’ll do a quick drawing for them.

“Oftentimes, the patient will ask to have it so they can show it to their family and help explain what we're going to do,” he said.

Early artistry

Art has always come naturally to Dr. Aboulhosn.

One of his earliest memories, as a 5-year-old in Lebanon, was lying under the couch. In his hidden space, the living room filling with guests, he sketched and doodled in his drawing book.

But his memories also included the deafening roar of fighter jets overhead during the country’s civil war. When he was 10 years old, artillery fire destroyed his home, and all his artwork burned to ashes.

The family eventually moved to Los Angeles. Finances were tight. His ambition to become a cartoonist was abandoned in favor of a less unpredictable profession: physician.

Scholarships, loans and side jobs as an artist put Dr. Aboulhosn through college and then the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. He did well – and enjoyed sketching and painting the human body during anatomy class – but medicine still paled in comparison to his dreams of being an artist.

Art and the heart

All that changed when he began his residency at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. Dr. Aboulhosn saw his first case of congenital heart disease, and “a light went off in my head.”

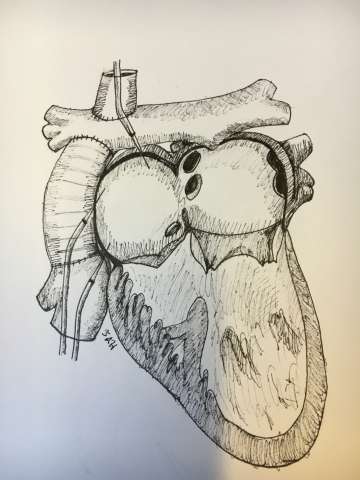

He pored over the patient’s CAT scan, intently studying the routing of a vein, how it connected to the heart. He pictured it in his mind and started to draw.

“Right away I realized congenital cardiology is a field where it's really clicking for me, like a Lego piece that finally found its home,” he said. “I think it was because of the art.”

A structural defect in the heart is the most common condition at birth, affecting about 1% of the human population. They can include a hole in the heart, a narrow aorta, or a heart on the other side of the chest. The structural variations are endless.

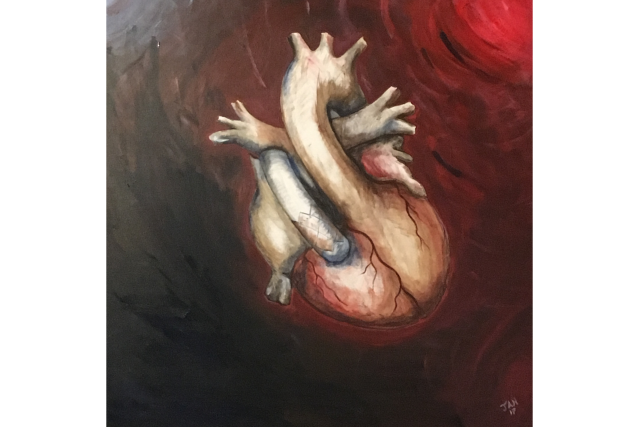

That complexity and the dynamic pumping that sets the heart apart from other organs, makes congenital heart disease “a veritable playground” for art, according to Dr. Aboulhosn.

That’s why art continues to play a role in his work as an interventional cardiologist. He uses minimally invasive techniques to repair heart conditions. And many of his novel procedures began as art.

“What I absolutely love is when somebody sends me a case where it's a real head scratcher,” said Dr. Aboulhosn. “I'll look at the anatomic imaging and then I'll just sit there with a pen or a pencil and I'll just sketch what I think I can do.”

In addition to advanced imaging, these sketches also help guide him in the cardiac catheterization laboratory, where he performs procedures to “navigate through the inside of the beating heart, implant the valve or place a stitch or close a hole, and understand where you are on an x-ray image.”

And Dr. Aboulhosn credits his art for another facet of his work. Besides his canvases of ink, charcoal or acrylics, he assembles dioramas depicting a historical scene, such as a spice trade caravan or military explorers. Painting these miniature figurines for hours on end has not only trained his focus but provided a steadiness and precision of hand.

“I truly feel that this kind of work helps me and my patients immensely.”

Art and connection

It’s not just his patients who benefit from his passion for art.

At Camp del Corazon, a program for children with congenital heart disease, Dr. Aboulhosn creates custom art for children and their families.

They describe their heart conditions and any surgeries they had, and, like a street artist, Dr. Aboulhosn draws a picture for the child.

And back at the hospital, student doctors learning about congenital heart disease under Dr. Aboulhosn soon find themselves with an extra challenge.

“If they're just spouting off words, I ask them, ‘What does that look like? Can you just draw it for me?’ And oftentimes they'll be really uncomfortable at the beginning,” said Dr. Aboulhosn, also a professor of cardiology at the medical school.

“I'm not expecting a masterpiece. I find one of the best ways to teach people complex anatomy is to have them sit down and actually draw it out.”

There is a reward for the physicians in the two-year Adult Congenital Heart Disease fellowship. For the last two decades, Dr. Aboulhosn has presented each graduating fellow with a custom-painted artwork that represents their time in the program.