Older people who undergo cancer surgery are more likely than their younger counterparts to experience injuries and health issues such as falling down, breaking bones, dehydration, bed sores, failure to thrive and delirium. These age-related issues may lead to longer hospital stays, increased health care costs and a greater risk of death, a UCLA study found.

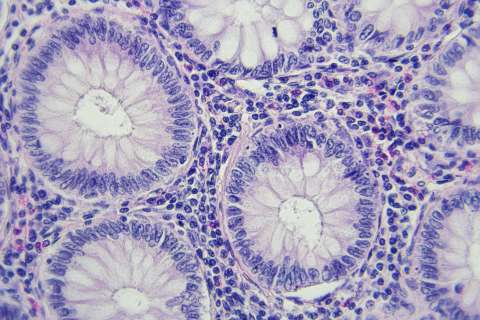

These problems can occur in addition to post-surgery complications, making them much more challenging to handle and more difficult for people to recover from. The study also found that they are especially frequent in people who undergo major abdominal surgery for cancer.

The 18-month study, which appeared today in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, brings to light issues related to frailty and reduced functionality, conditions of the elderly that tend to be overshadowed by more common objects of study, such as survival rates and chemotherapy toxicity. The findings could lead to better care planning and, the researchers hope, better outcomes for patients whose age puts them at higher risk, said Dr. Hung-Jui Tan, the study’s first author and a fellow in urologic oncology at UCLA.

“The findings highlight the importance for older patients to discuss these potential events with their doctors as they prepare for surgery,” Tan said. “Now that the prevalence of such events is known, treatment approaches that keep these age-related health concerns in mind may be better applied in the future to better assist these patients.”

As the American population gets older, this distinctive set of health issues will only become more common and more urgent to address.

“Even now, these events affect approximately one in 10 patients over the age of 54 undergoing cancer surgery in the United States,” Tan said. “With even higher rates observed among the very old, patients 75 and older — the fastest-growing segment of the population — geriatric events during cancer-related surgery are likely to become even more prevalent.”

For the study, researchers used nationwide data on hospital admissions for major cancer surgery in people aged 65 and older; they also studied a younger group of people, aged 55 to 64. Both groups of patients underwent operations between 2009 and 2011. The research team searched for specific age-related events and estimated their prevalence in relation to age, other health problems and the location of the cancer.

Within a total sample of 939,150 patients, the researchers identified at least one age-related event in 9.2 percent of cases, with much higher rates in patients 75 and older and those undergoing surgery for bladder, ovarian, colorectal, pancreatic or stomach cancer. The study also found that those patients experiencing age-related health issues had a greater risk of concurrent complications and of being discharged to rehabilitation facilities rather than their own homes.

Going forward, Tan and his team will work toward a better understanding of the relationship between geriatric events and other outcomes — examining, for example, the causal direction between age-related events and complications from surgery. The researchers will also work to develop proactive ways to address these health concerns for patients who need cancer surgery.

“These events may add to operative morbidity and resource utilization, straining both patients and the cancer care delivery system,” the study says. “Efforts aimed at addressing older age-related health concerns and reducing associated morbidity will be essential as the number of older adults with cancer continues to grow.”

Dr. Mark Litwin, chair of the department of urology, is senior author of the study.

The study was funded by the Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations through the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program, the American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institute on Aging.