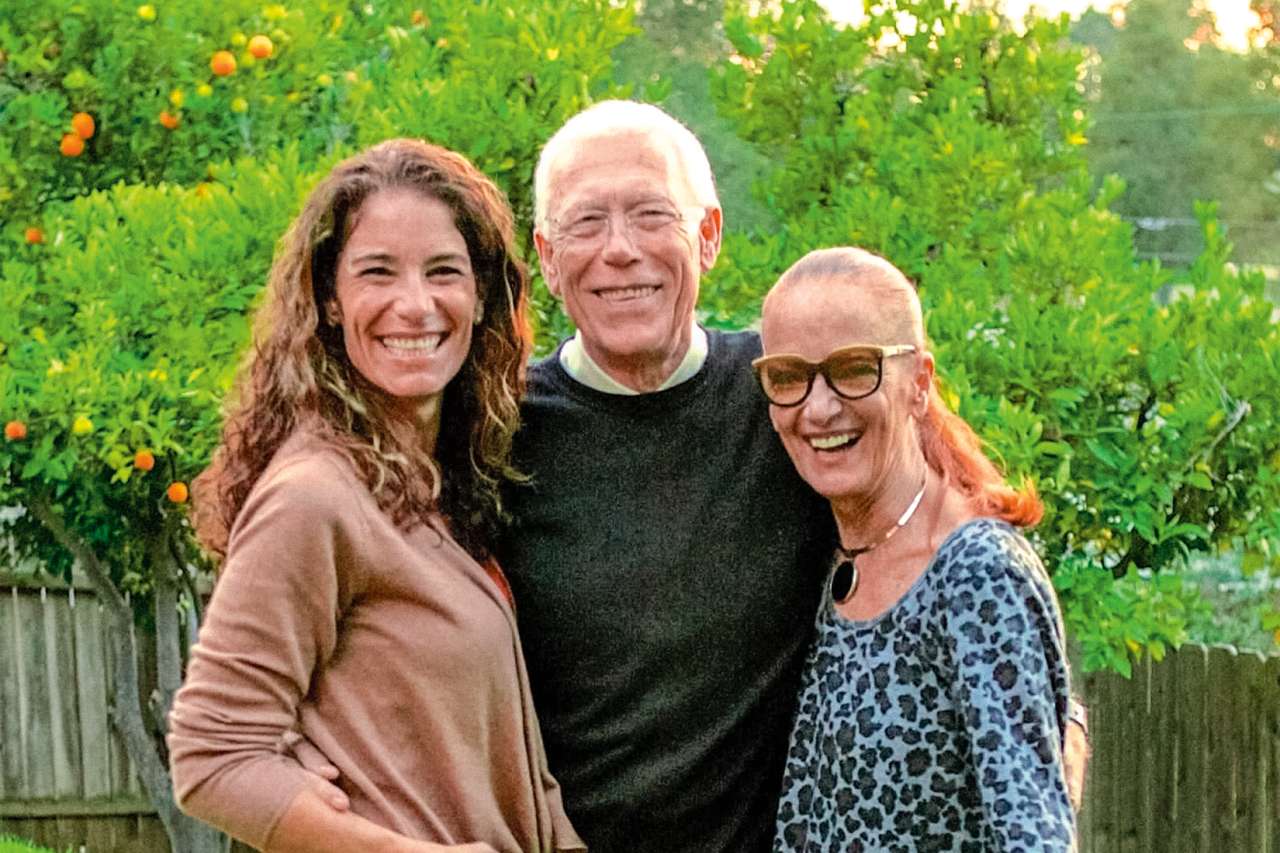

John Chadwick never meant to hit his wife. In fact, he thought he was defending her from a gang of thugs. But when her shouts woke him from a terrifying dream, he discovered that the face he was slugging belonged to Suzanne, his spouse of more than 30 years. “I was mortified when I saw what I was doing,” recalls the retired hairstylist, a soft-spoken British expat whose only previous acts of violence involved the eradication of split ends. “I was already ashamed of what had been happening to me at night. When she was hurt, it was 10 times worse.”

Chadwick was in his late 50s when his unnerving sleep troubles began. The first sign was twitchy legs; then came nightmares in which he and his family were under attack and he was fighting for their lives. Several times a week, Suzanne would be awakened by his flailing arms and bloodcurdling screams. Sometimes, he literally kicked her out of bed. Once, he bit her wrist so hard that the marks lingered for days.

Although the couple’s relationship was warm and loving, a psychiatrist suggested that Chadwick’s nocturnal behavior revealed unconscious rage. Yet, therapy failed to uncover any issues that might be fueling his Dr. Jekyll-and-Mr. Hyde-like transformations. Chadwick went to see a sleep specialist, who attributed his problems to stress and prescribed relaxation exercises. They didn’t help. After his punch left Suzanne with a black eye, he started spending his nights on the couch in the living room.

The move brought new dangers. In the grip of his nightmares, Chadwick toppled the sofa, hurled the TV out the window and nearly jumped out himself. To protect the household from his dreaming self, he decamped to the garage — where one night, he grabbed a paint scraper to ward off a phantasmic adversary and lacerated his hands.

Realizing that the problem lay less with his sleeping environment than with his ability to interact with it, Chadwick dragged his mattress to a spare bedroom. A talented craftsman, he sewed together nylon webbing and padded cuffs to create restraints for his hands and feet. For extra safety, he made a strap with a quick-release buckle to go across his chest and secure himself to the bed. But the system was impractical for travel. On a business flight to China, he awoke to find his fingers around the throat of his seatmate.

That incident drove Chadwick to seek out other specialists who might be able to address his condition, an odyssey that brought a string of contradictory diagnoses and frustrating treatments. The medications he was prescribed reduced the frequency of his episodes, but they left him groggy during the day and affected his coordination and gait. “He walked as if he was stepping in post holes,” says his adult daughter, Becky.

Concerned about her father’s physical, as well as emotional, health — he told her he feared he was losing his mind — Becky started to investigate online. Chadwick’s symptoms, she thought, pointed to a condition called rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder, or RBD. This perplexing ailment is a type of parasomnia, a sleep disorder characterized by unusual, disruptive behaviors. In RBD, the protective paralysis that normally accompanies REM sleep — the sleep stage during which dreams are most frequent and vivid — fails to occur. At the same time, dream content may become more violent and frightening. Patients act out their sometimes physically tumultuous dreams, risking injury to themselves and their bed partners.

When Becky asked for advice on a sleep-disorders message board, someone suggested she contact a researcher at the University of Minnesota, Carlos H. Schenck, MD, who identified the syndrome in the 1980s.

Dr. Schenck responded to Becky’s email with a tip of his own. “He wrote back, ‘Lucky for you, you’re in Los Angeles,’” she recalls. There’s someone at UCLA her father should see, he told her.

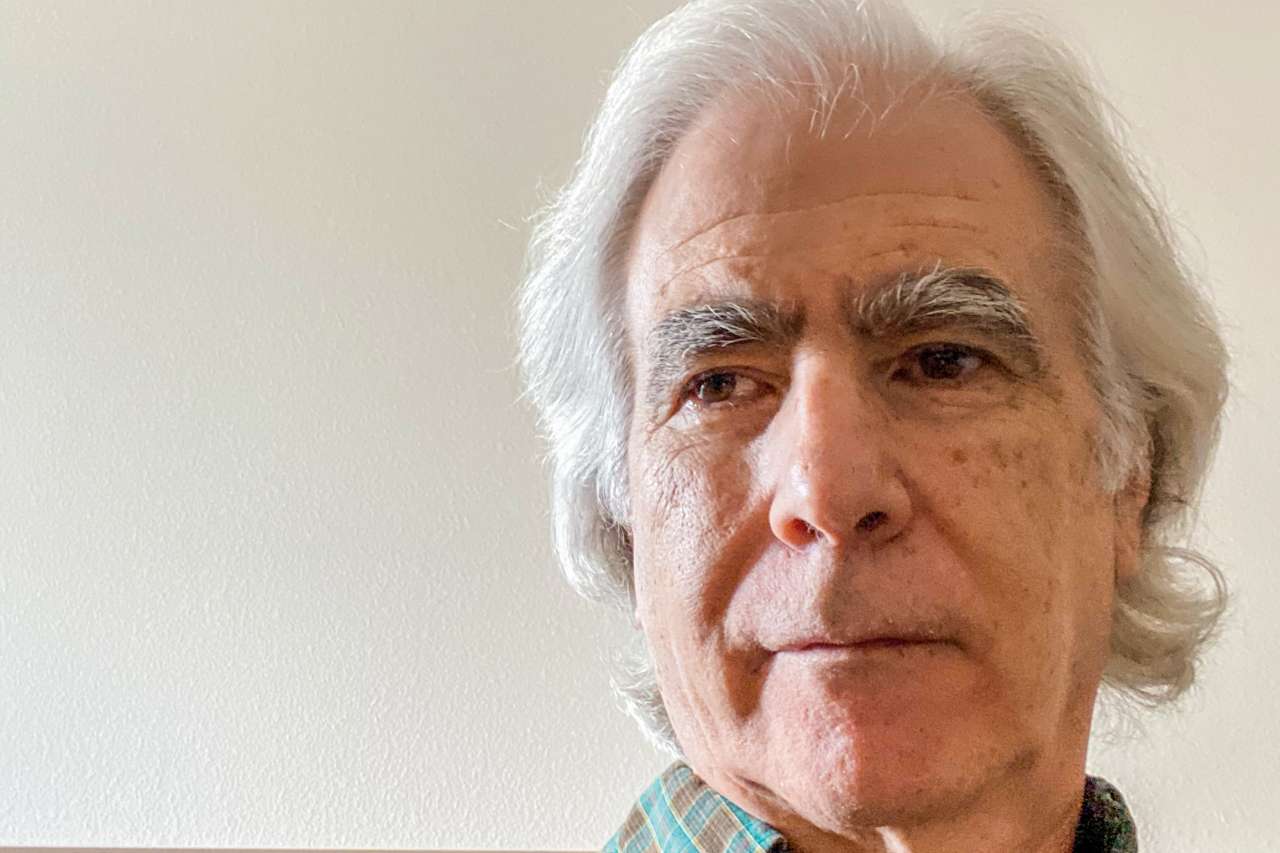

Alon Y. Avidan, MD, MPH, is a leading expert on REM sleep behavior disorder. He is the author of textbooks on sleep and key articles on RBD, and he has lectured extensively on the topic. He’s also one of the principal investigators for the North American Prodromal Synucleopathy (NAPS) Consortium, an alliance of nine academic health institutions coordinating research on RBD and its critical link to an array of neurodegenerative diseases.

“Physicians who encounter patients with RBD who present with dream enactment are sometimes unaware of its existence, and may even be dismissive of its symptoms,” Dr. Avidan, professor of neurology, observes. “They say, ‘Oh, it’s probably just nightmares, or it may be related to something you ate the night before. But this is a condition that upends patients’ lives, and the lives of their loved ones.”

Beside the physical perils — one of Dr. Avidan’s patients, an FBI agent, snatched a pistol from under his pillow during a dream about intruders and fired two bullets into the ceiling of a hotel room — RBD can destroy marriages. “It affects intimacy, because couples often have to sleep apart,” he explains. “It can also undermine trust, especially if a patient’s violent actions lead to a partner being badly hurt, and they suspect that the actions are directed at them.”

The condition affects an estimated 0.5% to 1.25% of the general population, and about 2% of people over age 60. But its importance in terms of public health belies those numbers — and not only because of all those suffering bed partners. “What’s unique about this sleep disorder,” explains Ravi S. Aysola, MD, chief of sleep medicine in UCLA Health’s Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine and director of the UCLA Sleep Center, “is that it can be predictive of more pervasive disorders that may develop in the future.”

Over the past decade, a raft of studies has shown that RBD can be a harbinger (in descending order of frequency) of Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies or a devastating disorder known as multiple systems atrophy. For patients diagnosed with isolated RBD (that is, with no known underlying cause), the risk of developing one of these illnesses is between 50% and 80% within a decade.

All these ailments have one thing in common: They are associated with Lewy bodies — clumps of misfolded alpha synuclein, a normally beneficial protein, that clog nerve cells. No one knows why such so-called alpha synucleopathies happen, how to prevent them or how to cure them. And that’s why the connection between RBD and synucleopathies intrigues researchers.

“REM sleep behavior disorder has the potential to give us valuable insights into Parkinson’s and related illnesses,” Dr. Aysola says. If biomarkers pointing to such disorders can be identified in RBD patients long before daytime symptoms occur, they could increase scientists’ understanding of the earliest stages of the neurodegenerative process. Eventually, they could also provide opportunities to administer neuroprotective treatment before the damage becomes irreversible. “By learning more about RBD,” he adds, “we can gain new insights about these future neurologic diseases.”

These perplexities and possibilities inform the studies that Dr. Avidan and other researchers focused on RBD are conducting in the United States and elsewhere. But to grasp both the challenges and promise posed by this disorder, it helps to know a bit about its history — and about the sleep stage it affects.

Even under normal circumstances, REM sleep is a strange beast. During this stage of slumber, which occurs at approximately 90-minute intervals throughout the night, the eyes jerk back and forth and up and down, as if the sleeper were watching an exciting movie, while the brain produces EEG patterns resembling those of waking. Although the phenomenon was first reported in 1953, by University of Chicago researchers Eugene Aserinsky, PhD, and Nathaniel Kleitman, PhD, it wasn’t until the end of the decade that another of its key oddities emerged. Experimenting with cats, French neuroscientist Michel Jouvet, MD, PhD, found their muscles went completely slack — a condition called atonia — while the animals were REMing.

In 1965, Dr. Jouvet made another momentous discovery: When he destroyed the tiny structure in the brainstem that triggered muscle atonia, cats acted out their dreams. They chased imaginary mice, defended themselves against imaginary attackers and fled from imaginary pursuers, all the while remaining unaware of the real world around them. This led the scientist to theorize that atonia during REM sleep served a simple purpose: to keep dreaming animals from such potentially disastrous shenanigans.

Nearly two decades later, a man in his 60s came to see Dr. Schenck, a psychiatrist and sleep researcher, at his sleep center in Minneapolis. For several years, the patient had experienced what he called “violent moving nightmares,” during which his punches and kicks sometimes injured his wife. He signed up for a night in the sleep lab after slamming into a dresser — and gashing his forehead — during a dream in which he was playing football. Tests showed that, like one of Dr. Jouvet’s neurosurgically altered cats, he was exhibiting REM sleep without muscle atonia.

By 1986, Dr. Schenck had identified four more patents with a similar syndrome. With the center’s director, neurologist Mark Mahowald, MD, he published a report on these cases in the journal Sleep. The following year, the pair coined a name for this new parasomnia: rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder — RBD. “After that,” Dr. Schenck recalls, “these types of patients started coming to us from all over.”

Early on, he and his team found that clonazepam (a benzodiazepine sedative), which had been used successfully to treat a more-common disorder, periodic limb movements during sleep, could control symptoms in most RBD patients. They also noticed that these patients shared several characteristics. The majority were men, and almost all were middle-aged or older. Rarely did their dreams involve initiating aggression; instead, the sleepers were responding to attacks — typically by unfamiliar people, animals or insects.

Other commonalities became clear only later. “Half of our patients had a neurological disorder that triggered their RBD, like a stroke, multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Schenck says. “But the other half were neurologically clean.” After 10 years, however, a pattern began to emerge: More than one-third of those “clean” patients had developed Parkinson’s-like disorders.

Dr. Avidan’s interest in sleep medicine emerged around that time, while he was a resident in neurology. During fellowship training, he became interested in parasomnias — the panoply of disruptive disorders that includes sleepwalking, sleep sex, sleep eating, night terrors, bedwetting and RBD. The latter particularly captured his imagination. “Interpreting sleep studies and watching videos of patients with parasomnias and RBD reminded me of scenes from The Exorcist,” Dr. Avidan says. “In another era, they would have been seen as demonically possessed.”

Dr. Avidan joined UCLA’s faculty in 2006, after heading the sleep disorders clinic at the University of Michigan (during which time he met and began collaborating with Dr. Schenck). He went on to publish extensively on the subject of RBD, including guidelines on how to distinguish it from other conditions that can produce violent or complex behaviors during sleep, such as night terrors, which occur during non-REM sleep and are typically not connected to dreaming; seizure disorders, in which body movements are stereotypical and patients are not easily awakened; post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), in which people relive a horrific scene they experienced in the past; or somnambulism, in which sleepers might make jam-and-cat food sandwiches or urinate in a wastebasket, but remember nothing upon waking. He also contributed to the development of new protocols for identifying RBD through polysomnography — nightlong monitoring of brainwaves, muscle impulses, eye movements and respiration.

As every physician knows, finding the correct diagnosis is key to choosing the right therapy for any patient. But with RBD, that choice is not always straightforward. Although clonazepam has a long track record, the hormone melatonin has shown to be at least as effective for many patients, with less tendency to cause daytime drowsiness. For other individuals, however, neither approach controls symptoms, or their side effects are intolerable.

When Chadwick arrived at UCLA in May 2008, with wife Suzanne and daughter Becky, Dr. Avidan took a detailed clinical history and performed a physical exam, neurological workup and sleep study. After confirming a diagnosis of RBD, he changed the patient’s medication, placing him on melatonin while reducing his original dose of clonazepam. Chadwick’s grogginess and gait problems cleared up swiftly, while his dream-enactment behaviors diminished in frequency and severity. Eventually, he felt secure enough to give up his bed restraints — and today, at 80 years old, he has only four or five mild episodes a month. Remarkably, he has also remained free of Parkinson’s or other synucleopathies, though he is battling several unrelated health problems.

Not all therapeutic puzzles can be solved so neatly, however. That was the case for Dan Reder, an IT manager who broke a finger during an RBD episode in 2016 and found his way to UCLA. Reder also suffered from severe insomnia, complicating his therapeutic needs.

After counseling the 65-year-old on how to create a safe sleeping space (no unprotected windows, no sharp-edged furniture, nothing that can be used as a weapon), Dr. Avidan started him on high-dose melatonin, which improved both his insomnia and his RBD symptoms, but left him too sleepy to function the next day. When a lower dose failed to control Reder’s dream enactments, Dr. Avidan added clonazepam to the regimen, but the combination again impaired the patient’s daytime alertness. A switch to temazepam — a shorter-acting benzodiazepine — solved that problem, but Reder continued to have RBD episodes once or twice a week, particularly when stress levels were high.

To lessen their impact, Reder suggested an approach he’d learned about on his own: a device that triggered a voice alert when a sensor indicated that a sleeper’s movements had become excessive. Over the following months, Dr. Avidan implemented a regimen that incorporated a Posey bed alarm — which played a recording of Reder’s wife, Claudia, calmly urging, “Wake up, Danny, you are just having a dream” — with an ongoing course of melatonin and temazepam.

Reder’s RBD episodes have grown far less intense. So has his daytime fatigue. Best of all, he and Claudia are still able to share a bed, albeit with a barricade of pillows between them. “The scariest thing about this disorder is the loss of control,” he says. “I’m grateful to be able to regain it.”

The challenges of controlling RBD extend to its possible long-term implications. For that reason, some physicians are uncomfortable informing newly diagnosed patients that the disorder can be a harbinger of future neurodegenerative conditions. If nothing can be done to prevent or cure those neurologic disorders, the thinking goes, why mention them at all?

Dr. Avidan disagrees with that reasoning. In March, he coauthored a paper with Dr. Schenck and other colleagues in the journal Seminars in Neurology, titled “Ethical Aspects of Prodromal Synucleineopathy Prognostic Counseling.” The team examined the pros and cons of disclosing the association of RBD with Parkinson’s-like diseases in a wide range of scenarios. The decision, they concluded, should be made on a case-by-case basis only after asking patients what they already know and whether they’re interested in finding out more.

As a rule, however, the authors favored transparency and a shared decision-making approach — partly because surveys show that’s what most patients want, and partly because many will go ahead and research their diagnosis on the internet. “Not only might learning this information on one’s own be alarming,” they wrote, “but it might also undermine trust in the physician if this had not been previously broached as a topic for discussion.”

Adds Dr. Aysola, director of the UCLA Sleep Center: “They’re going to be more vulnerable to misinformation they find online if they don’t get the real facts from us first.”

Dr. Avidan makes a point of asking patients if they have investigated RBD on their own, and then, “If RBD predicted a neurologic condition, would you like me to review that with you? Some people say, ‘I’d rather not know. I’m already in my late 80s, and I’d rather live without the anxiety.’ But most patients do want to know, so that they can be more proactive — whether that means enrolling in a clinical trial to delay or slow down progression to incorporating lifestyle changes that might slow the course of the disease or taking an adventurous vacation now instead of 10 years from now.”

As site principal investigator for the NAPS Consortium, Dr. Avidan and colleagues at UCLA Health are conducting research to prepare for future neuroprotective clinical trials for alpha synucleopathies. The data they gather will be used to develop biomarkers to identify people at risk for synucleopathies in the presymptomatic stage, a crucial step for learning how to combat these scourges.

Other efforts to identify such markers are already underway — including a study led by Dr. Avidan and Gal Bitan, PhD, professor-in-residence of neurology. The team has devised a blood test based on brain-derived exosomes (neurofilaments and proteins that enter the bloodstream from the central nervous system), which can detect elevated alpha-synuclein levels in people with RBD. They’re currently investigating how these assays could be used to gauge a patient’s likelihood of progressing to Parkinson’s or other synucleopathies.

“The hope is that if we can catch these at-risk patients early enough, we can protect them from developing future neurodegenerative conditions,” Dr. Avidan says. “RBD is the canary in a coal mine that could help us stop neurodegeneration in its tracks.”

Kenneth Miller is a science writer whose work has appeared in Time, Discover, Mother Jones and Prevention, among other publications. His new book, Mapping the Darkness: The Visionary Scientists Who Unlocked the Mysteries of Sleep (Hachette Books, 2023), was published in October.