Long and exhausting hours during the COVID-19 pandemic brought on a crisis of burnout among health care workers, Jane Fazio, MD, among them.

The pulmonologist and critical care fellow was especially distressed by the disparities she saw at the four hospitals she rotated through. The inequities inspired her to add research to her fellowship experience through a PhD in health policy and management at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

“I thought I could actually do a lot more in research than I could do clinically, because medicine has limits, and they're very real limits,” said Dr. Fazio, a clinical instructor in the department of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. “Research can be really rewarding because it gives you that time to be creative: think of problems you want to solve and ways of solving them.”

Her foray into research was made possible by the Specialty Training and Advanced Research Program (STAR Program) at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

STAR is a unique physician-scientist training program for both MD-PhD graduates and for those wishing to obtain a PhD. STAR hosts 50-60 fellows per year and has had 250 graduates since 1993. During their fellowship, physicians complete both clinical and research training in about five years.

STAR provides intensive research training later in the physician-scientist journey compared with the traditional medical scientist training program which commences years earlier during medical school. As Dr. Fazio puts it, she believes she boarded “the last stop on the research train.”

“Having people who are well versed in diseases also involved in science is really important,” said Linda Demer, MD, PhD, co-founder and executive co-director of the STAR Program, and vice chair of the department of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. “Serendipity is a big part of science, and having the breadth of knowledge that physicians have, and being aware of all the nuances of diseases, can make them more ready to spot the potential applications to human health.”

Dr. Fazio’s clinical work directly informed her research. After treating an alarming number of patients with silicosis, she researched risk factors and screening methods for the occupational lung disease and consulted with public health officials in California to institute safeguards for workers in the stone countertop fabrication industry.

Most recently, regulators in the state passed a set of workplace safety rules.

Cross training

The first year of the STAR Program is similar to any fellowship, with full-time clinical training. Subsequently, research training is added into the mix, at a proportion similar to faculty physician-scientists: 70-80% of their time for research and 20-30% seeing patients.

Fellows choose one of three research tracks in STAR, including basic science, health services/outcomes and postdoctoral. A fourth STAR track is for internal medicine residents.

The program helps physicians not only find a research mentor but strongly encourages them to choose at least one mentor from a different division, department or school.

For example, one cardiology fellow studied PET imaging with a cancer researcher. (He went on to become president of the American Heart Association and director of a cardiovascular institute.) Some trainees head to the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. One fellow interested in the problem of “food deserts” got his PhD in urban planning at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs.

The cross training broadens their experience and offers a competitive advantage for future careers.

“We have them train in science as much as possible with somebody outside their clinical division, and that way they're bringing new knowledge and skills to the division that will be hiring them as a faculty member,” said Dr. Demer, a distinguished professor in the departments of medicine, physiology and bioengineering.

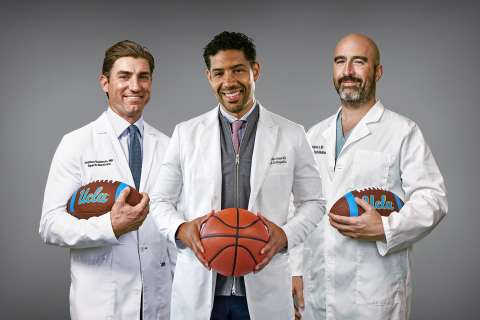

After graduating from STAR a decade ago, Tamer Sallam, MD, PhD, stayed on at UCLA Health and is executive co-director of the STAR Program. The cardiologist earned his doctorate in molecular, cellular and integrative physiology, and now directs the UCLA Health Preventive Cardiology and Cardiometabolic Health Program.

“The hope is that they uncover the mysteries of the diseases they treat, paving the way for groundbreaking discoveries,” said Dr. Sallam, vice chair and an associate professor in the department of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

He trained with Peter Tontonoz, MD, PhD, investigating lipid metabolism, the same lab Giuliana Repetti, MD, recently joined. A cardiology fellow, Dr. Repetti is enrolled in the basic science track.

“I don't always know how to ask the right questions because I'm still receiving training in that,” Dr. Repetti said. “But because I'm a doctor, I do know what questions are relevant and important for human disease.”

It's rewarding to watch talented STAR trainees like Dr. Repetti continue to succeed, according to Dr. Sallam. Fellows are “the architects of tomorrow’s medicine,” he said.

Career development

Doctors well versed in research have been behind some of the biggest advances in medical science. Dr. Alexander Fleming, a physician and microbiologist, discovered penicillin. Dr. Jonas Salk and Dr. Albert Sabin developed polio vaccines. More than a third of the winners of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine are physician-scientists.

Yet, they are “getting down to extinction level,” according to Dr. Demer. Physician-scientists dropped from 4.7% of the biomedical workforce in the 1980s to 1.5% today.

The STAR Program is doing its part to train the next generation of physician-scientists, and it has a noteworthy record of graduates maintaining research careers.

“Critical to the success of awardees is a close partnership with sponsoring departments which plays a key role in providing career support and resources,” said Dr. Sallam.

A study that tracked the first two decades of the program found that more than 80% of graduates were researchers in academia or biotechnology, and 71% had academic appointments – remarkable results still going strong, according to Dr. Demer, who is also co-director of the Office of Physician-Scientist Career Development (OPSCD) at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

The OPSCD plays an important part in STAR fellows’ experience, right from entry into the program, and helps make “the uncertainty of becoming a scientist a little more certain,” said Mitchell Wong, MD, PhD, director of the OPSCD.

A significant factor in a scientific career is funding, especially as grants, such as from the National Institutes of Health, become ever more competitive. With so much riding on grant applications, the OPSCD holds bootcamps in which small groups receive weekly training, mentorship and review of applications.

In addition, peer mentoring groups provide a forum for early career investigators and a faculty moderator to bond over monthly breakfasts and chat about issues such as the demands of research and clinical work, negotiating authorship in a collaboration, and work-life balance.

Additional networking can be found in ASCEND, a new initiative of the OPSCD for Advancing Scientific Careers and Excellence in Physician Development, which comprises panel discussions, informal peer meetings and individualized career advice.

“Becoming a physician-scientist is a big-time commitment and there are a lot of ups and downs and rejection that you have to get through,” said Dr. Wong, a professor in the department of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and a STAR graduate.

“The STAR Program is more than just the training of doing the science, but the training of a scientific career. So we provide mentors and directors who are really thinking about career training.

“One particular advantage of having a larger structure with 50-60 fellows is that a lot of what you learn as a scientist, you learn from your peers. You learn a lot from other individuals who are at your same stage, even if they're not doing research that's directly related to your own. A lot of the skill set in terms of navigating the process and writing papers and networking happens among people at your same level.”