Unless you’ve just given birth, you probably never think about your pelvic floor. Yet this network of muscles is integral to healthy human functioning, including urination, defecation and sex.

“Our pelvic floor works for us all the time in many different ways,” says Emily Whalen, DPT, a pelvic floor physical therapist with UCLA Health and educator with the Simms/Mann-UCLA Center for Integrative Oncology. “So when there are impairments in those muscles, lots of personal issues can end up resulting from that.”

Even though everyone with a pelvis has a pelvic floor, the problems that arise when these muscles aren’t working properly can be difficult to talk about: urinary and fecal incontinence, pelvic pain and pain during sex.

“There’s a lot of emotional heaviness with pelvic floor dysfunction,” Dr. Whalen says. “Whether it’s leakage or pain or any combination, it’s just emotionally really challenging.”

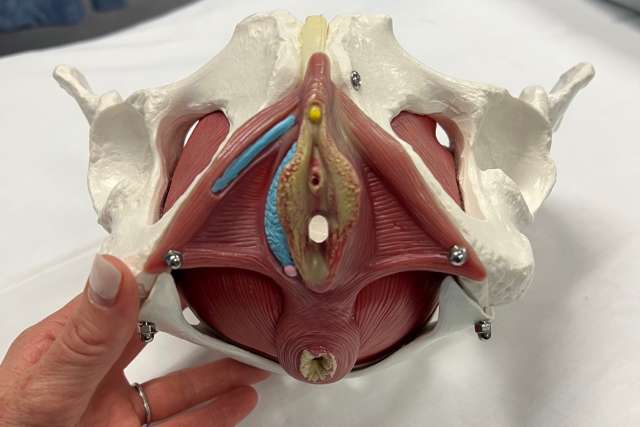

What is the pelvic floor?

The pelvic floor is a group of muscles that stretches from the pubic bone to the tailbone, supporting the pelvic organs including the bladder, urethra, bowel, rectum and anus. The pelvic floor also supports the vagina and uterus in female bodies and the prostate in male bodies.

A healthy pelvic floor can contract, squeeze, lift and relax.

“It has a range of motion just like any other muscle does. It’s just not a very big range of motion,” Dr. Whalen says.

An individual with a healthy pelvic floor can voluntarily contract these muscles, which feels like holding in urine or holding back gas, Dr. Whalen says. Healthy functioning also allows the muscles to completely relax and release to allow for urination or bowel movement.

“That’s the range of motion: it should be able to go from fully contracted to fully relaxed,” she says.

Various health conditions and life experiences can cause these muscles to become strained, weakened or overly tight.

Injuries and problems with the pelvic floor

Vaginal delivery during childbirth can injure the pelvic floor, says Dr. Whalen: “I see it as a strain or sprain to the pelvic floor anatomy.”

This injury can cause pain with intercourse, urine leakage and even difficulty lifting the baby into a car seat.

Just like a sprained ankle or wrist needs rest and possibly physical therapy to support recovery, so does a sprained pelvic floor. But because we don’t see our pelvic floor the way we can see our ankle or wrist, and talking about pelvic issues isn’t easy, “people often suffer in silence,” Dr. Whalen says.

“Really, it’s just anatomy; it’s just an injury that needs to be loved and rehabbed back to normal health,” she says.

Cancer treatments can also cause pelvic floor problems. People treated with a prostatectomy — surgical removal of part or all of the prostate gland — may experience urinary incontinence that can be mitigated by strengthening the pelvic floor, Dr. Whalen says. Because the prostate supports the urethra, its removal means the pelvic floor has to work harder than before to compensate.

Chemotherapy and radiation can also affect pelvic floor function.

“When there’s radiation, there’s scar tissue. And if it’s a vulvar or vaginal cancer and there’s surgery, there’s scar tissue,” Dr. Whalen says. “And it’s just like scar tissue anywhere else — if you’ve had knee-replacement surgery, you have to come to physical therapy to make sure everything moves and continues to be able to provide the function it’s there to do.”

People with a rare condition called vaginismus, in which the muscles of the vagina remain involuntarily contracted, can find relief through pelvic floor physical therapy, as can people who undergo gender-affirming vaginoplasty.

What is pelvic floor physical therapy?

People experiencing incontinence or pelvic pain and people recovering from cancer treatment can be referred to one of several pelvic floor physical therapists at UCLA Health. Pelvic floor physical therapists also work with the Simms/Mann Center to support patient education and recovery.

An appointment with a pelvic floor physical therapist begins with a review of the patient’s medical history and a discussion of their symptoms. For some patients, this conversation can be very emotional, Dr. Whalen says: “It’s not uncommon for a patient to sit down and not even say a word and the tears start flowing.”

Prolonged pain is already an emotional burden, she says, compounded by the intimacy of the physical location of the pelvic floor and the functions it controls.

A physical therapy appointment also includes visual and physical assessment of pelvic floor strength before the therapist guides the patient through breath work and other exercises to engage the pelvic floor muscles. Patients are given a personalized set of exercises to perform at home between appointments.

“Patients don’t get better just by coming to the clinic,” Dr. Whalen says. “They have to do the homework.”

It takes 12 to 16 weeks to strengthen any muscle, she says, and improvements in pelvic floor strength take three to four months of daily exercise.

Keeping the pelvic floor healthy

No gym membership is required to exercise the pelvic floor. This web of muscles can be contracted and relaxed anytime, anywhere, without anyone else knowing. But it can be difficult to identify and connect with the muscles of this area at first.

Exercising the pelvic floor involves squeezing and releasing the muscles used to stop the flow of urine or to prevent passing gas. People often draw on other muscle groups — including the thighs and buttocks — when trying to engage the pelvic floor, Dr. Whalen says. With time and practice, however, people learn to isolate these muscles and contract and relax them at will.

“The pelvic floor is anatomy, just like anywhere else in the body. Even though it’s a private area and so sensitive — literally physically sensitive and also emotionally sensitive — it responds to physical therapy the same way as any other area of the body,” Dr. Whalen says. “So if there is any concern, people should ask their doctor. They should not be nervous or anxious about mentioning it to a provider because it’s just like anywhere else.”