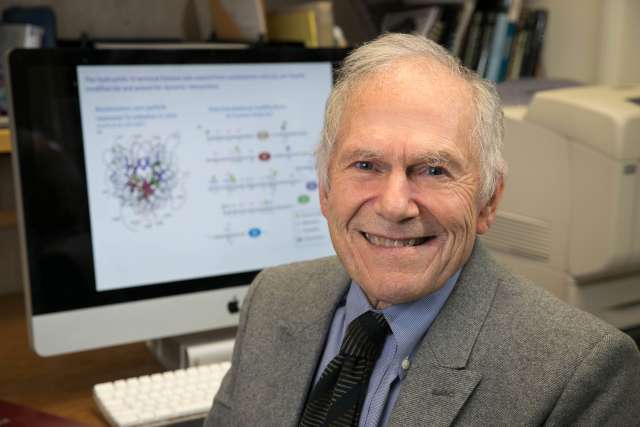

Michael Grunstein, a distinguished professor emeritus of biological chemistry at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and pioneering scientist who helped make genetic cloning possible, has died. He was 77.

Born in Romania and the only surviving child of two Holocaust survivors, Grunstein joined the UCLA faculty in 1975. He served as chair of the department of biological chemistry from 2007–10 and retired in 2016.

Grunstein, an elected member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, succumbed to complications of Parkinson’s disease on Feb. 18. He was surrounded by family in his Southern California home.

He received widespread recognition for his groundbreaking research, including the Massry Prize in 2003, the Rosenstiel Award for Distinguished Work in Basic Medical Research in 2011, the Gruber Genetics Prize in 2016, the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award in 2018 and the Albany Prize in 2022. These awards were shared with the late C. David Allis of Rockefeller University.

Much of Grunstein’s research focused on histones, the protein “spools” around which DNA wraps itself, allowing the genetic material to be tightly coiled and packed within chromosomes in the microscopic confines of a cell’s nucleus. Thanks in part to his groundbreaking work, scientists now understand that histones supply more than just structural support — they also regulate gene expression. Grunstein’s laboratory demonstrated that histones can switch genes off in living cells and that modifying these histones help switch genes on.

Gene expression plays an important role in the development of every aspect of the body, and understanding histones’ role in the process has provided a deeper insight not only into normal development but into the diseases and disorders that can result when the process goes awry.

“Reflecting on Michael’s journey, we can discern the key attributes that lead to scientific breakthroughs,” Dr. Siavash Kurdistani, professor and chair of biological chemistry, said in an email announcing Grunstein’s death. Grunstein served as Kurdistani’s postdoctoral advisor.

“Curiosity led him to find fascination in what many considered mundane — packaging proteins,” Kurdistani said. “Creativity guided him to explore questions overlooked by others. ... Willingness to follow nature and experimental results allowed him to perceive that packaging proteins play important roles in gene regulation. Resolve and luck enabled him to make the best of what was available to him, culminating in seminal contributions to science.”

When Grunstein was 6, his family moved to Montreal, where he earned an undergraduate degree in genetics and chemistry from McGill University. At a faculty member’s suggestion, he traveled abroad for graduate school, earning a doctorate in molecular biology from Scotland’s University of Edinburgh.

Grunstein conducted his postdoctoral training under scientists Larry Kedes and David Hogness at Stanford University, where he invented a new technique called colony hybridization. The approach allowed researchers to isolate a single gene from a mixture pool of thousands or millions of pieces of DNA. His breakthrough provided the missing tool that would make it possible to clone individual genes. Scientists soon adapted the principle behind the technique to clone genes in bacterial viruses, yeast and human cells.

In 1975, UCLA invited Grunstein to set up his own laboratory on campus as a new professor. In an elegant series of experiments over 15 years, he pioneered the genetic analysis of histones in yeast and demonstrated that histones regulate gene activity in living cells. He also demonstrated that the presence or absence of a particular chemical group, known as an acetyl group, at certain spots within histones helps turns genes on and off. His discoveries propelled the field of epigenetics to the forefront of science, driving investigations into the molecular events underlying the development of human diseases, including cancer.

For much of his time at UCLA, Grunstein was a researcher with UCLA’s Molecular Biology Institute and the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Beyond his scientific endeavors, Michael had a passionate interest in gardening,” Kurdistani said. “At its peak, his garden was yielding an impressive three tons of avocados annually, in addition to a bountiful variety of other fruits and vegetables.”

Grunstein is survived by his wife, Judy, daughter Davina, son Jeremy and four grandchildren.

Private services were held on Feb. 21. The department of biological chemistry is planning a memorial this spring.

The family suggests donations to the Parkinson’s Foundation.