The study, which focuses on diabetic rodents, appears this month in PLoS One and is the first to show a role in glucose metabolism for humanin, a small protein (peptide). The researchers also demonstrated that humanin resembles the peptide leptin by acting on the brain to influence glucose metabolism.

Humanin is found in mitochondria - structures that populate the cytoplasm of cells and provide them with energy. The peptide was first detected in brain nerve cells in 2001, and subsequent studies suggest that it protects nerve cells from death associated with Alzheimer's and other brain disease.

"This new role of humanin in glucose metabolism, in addition to its role in Alzheimer's disease, is very intriguing since scientists have long proposed a link between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer's disease," says Nir Barzilai, M.D., a co-senior author of the study, the Ingeborg and Ira Leon Rennert Professor of Aging Research, and director of the Institute for Aging Research at Einstein."Humanin could turn out to be a therapeutic option for two common debilitating diseases that affect millions of people. Additionally, humanin may help treat other age-related diseases."

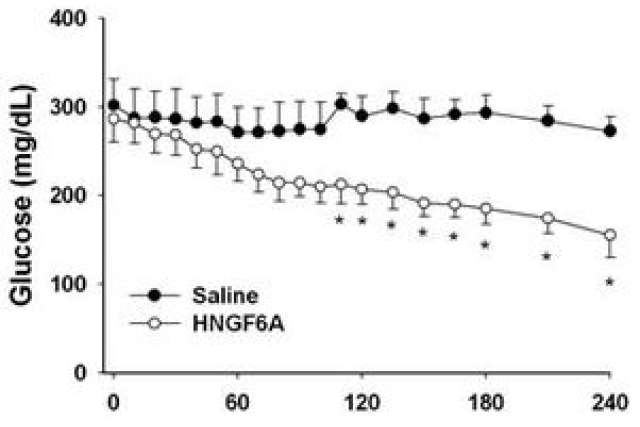

In the study, Dr. Barzilai and his colleagues infused humanin into the brains of diabetic rats to determine the peptide's effect on glucose metabolism. The infused humanin significantly improved overall insulin sensitivity, both in the liver and in skeletal muscle. Furthermore, a single treatment with a highly-potent form of humanin significantly lowered blood-sugar levels in diabetic rats.

"The improvement in insulin sensitivity caused by centrally administered humanin may be one of the main mechanisms through which humanin regulates cell survival," says Dr. Barzilai. "This may provide another potential mechanism by which humanin protects against Alzheimer's disease."

Humanin's possible link to two age-related diseases — Alzheimer disease and Type 2 diabetes — prompted the researchers to investigate whether age-associated changes in humanin levels occur in rodents and in humans. They found that humanin levels in two brain structures (the hypothalamus and the cortex) and in skeletal muscle decreased with age in rodents, and that circulating blood levels of the peptide decreased with age in people.

"From these results, we conclude that the decline in humanin with age could help explain why Alzheimer's disease and type 2 diabetes are more common in older people," says Dr. Barzilai.

Furthermore, "the remarkable activity of this novel peptide proposes a new role for an emerging class of endogenous molecules derived from the mitochondria that have previously been overlooked and can potentially represent a different paradigm for drug development for a variety of diseases," says Dr. Pinchas Cohen, co-senior author, professor and chief of endocrinology at the UCLA Mattel Children's Hospital, and co-director of the UCSD/UCLA Diabetes/Endocrinology Research Center at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

The researchers are currently studying the pharmacokinetics and safety profile of humanin and its analogues.

The paper, "Humanin: A Novel Regulator of Peripheral Insulin Action," is published in the July 22, 2009 issue of PLoS One, a journal of the Public Library of Science.

The lead author is Radhika H. Muzumdar, M.D., M.B., assistant professor of pediatrics and of medicine at Einstein. The co-senior authors are Drs. Barzilai and Cohen, with Dr. Barzilai serving as corresponding author. Co-authors include Gil Atzmon, Tamuri Budagov, Linguang Cui, Francine Einstein, Sigal Fishman, and Derek Huffman, Einstein; Aruna Poduval, Children's Hospital Montefiore; Christoph Buettner, Mount Sinai School of Medicine; and Laura Cobb and David Hwang, UCLA.

Funding and Financial Disclosure: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. No pharmaceutical or commercial support contributed to this manuscript. There are no conflicts of interests for any of the investigators.

Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University is one of the nation's premier centers for research, medical education and clinical investigation. It is the home to some 2,000 faculty members, 750 M.D. students, 350 Ph.D. students (including 125 in combined M.D./Ph.D. programs) and 380 postdoctoral investigators. Last year, Einstein received more than $130 million in support from the NIH. This includes the funding of major research centers at Einstein in diabetes, cancer, liver disease, and AIDS. Other areas where the College of Medicine is concentrating its efforts include developmental brain research, neuroscience, cardiac disease, and initiatives to reduce and eliminate ethnic and racial health disparities. Through its extensive affiliation network involving five hospital centers in the Bronx, Manhattan and Long Island - which includes Montefiore Medical Center, The University Hospital and Academic Medical Center for Einstein - the College runs one of the largest post-graduate medical training program in the United States, offering approximately 150 residency programs to more than 2,500 physicians in training.

UCLA Mattel Children's Hospital is one of the highest-rated children's hospitals in California, is a vital component of Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, ranked by U.S. News & World Report as the No. 3 hospital in nation and best in the Western United States. Mattel Children's Hospital offers a full spectrum of primary and specialized medical care for infants, children and adolescents. The hospital's mission is to provide state-of-the-art treatment for children in a compassionate atmosphere and to improve the understanding and treatment of pediatric diseases.