UCLA researchers knew - based on two clinical trials - that a subset of kidney cancer patients responded well to an experimental targeted therapy, but they didn't know why. If they could determine the mechanism behind the response, they would be able to predict which patients would respond and personalize their treatment accordingly.

Extrapolating from the clinical responses, Jonsson Cancer Center scientists uncovered the cascade of molecular events by which the cancer cells in a subset of patients became sensitized to the experimental drug CCI-779. Armed with this information, UCLA researchers are developing a test to identify which patients will benefit from receiving CCI-779.

The research, published this month in Nature Medicine, takes researchers a step closer to personalized medicine - treating cancer patients not with a one-size-fits-all therapy but with a treatment based on the specific molecular signature of their cancer cells.

"We knew there were certain kidney cancer patients who responded to this drug, but we didn't know the mechanism behind the response," said George Thomas, first author of the study, an assistant professor of pathology and a Jonsson Cancer Center researcher. "We had to determine the mechanism of response so we could identify the responders."

Thomas, with Jonsson Cancer Center researchers Dr. Ingo Mellinghoff and Dr. Charles Sawyers, discovered that human kidney cancer cells that had lost the tumor suppressor gene Von Hippel Lindau (VHL) were more sensitive to the growth inhibitory effects of CCI-779. One of the main functions of VHL is to regulate a protein called hypoxia inducible factor (HIF). When patients lost VHL, they had high levels of HIF. Thomas said the cancer cells became dependent on HIF to grow, so high levels of the protein gave the cancer cells a growth advantage.

CCI-779 had previously been tested at UCLA in prostate cancer patients and researchers knew it targeted the mTOR protein. Previous studies also had shown that inhibitors of mTOR also might inhibit HIF.

"We theorized that by inhibiting mTOR, which contributes to HIF levels, we might be able to significantly reduce HIF and remove the growth advantage the cancer cells had," Thomas said. "Because we now know the mechanism that is fueling the growth of the cancer cells, we can identify patients who will respond to this drug."

About 50 to 70 percent of kidney cancer patients have lost VHL, Thomas said. Their tumors, therefore, will have high levels of HIF and likely will respond to the drug. This finding could potentially help about 20,000 kidney cancer patients every year.

Typically, scientists seeking a target for a new cancer therapy start work in cell lines and then advance to laboratory animals to test their theories. Working backward from responses in clinical trials is unusual, Thomas said. Responses observed in clinical studies led researchers back to the laboratory. Their laboratory findings will be tested in further clinical studies, bringing the observation full circle, from the patient to the lab and back to the patient again.

In this case, CCI-779 was being tested at UCLA in a Phase I study on patients with a variety of advanced cancers. Researchers noted that patients with kidney cancer seemed to respond better to the drug than patients with other cancer types. That led to a Phase II study solely in kidney cancer patients. That study showed that a subset of patients had a complete response, while a high percentage experienced partial responses or had their disease stabilize, meaning it was no longer growing.

Thomas predicted that CCI-779 would probably be most effective when given in combination with other therapies because it "in kidney cancer, it stops the tumor cells from growing, it doesn't kill them." It could be paired with conventional chemotherapy or with another targeted therapy, such as an angiogenesis inhibitor, which cuts off the independent blood supply that cancers need to grow and flourish. The CCI-779 would stop the growth of the cancer, and the chemotherapy would be used to kill the cancer cells or the angiogenesis inhibitor could be administered to cut off the blood supply to the tumor, stopping the flow of oxygen and nutrients that the tumor needs to survive.

Standard of care for kidney cancer is almost always removal of part or the entire kidney, so that tissue could be tested for the molecular signature that indicates response to CCI-779. Doctors could then decide on what treatment to use in those likely to respond to the drug.

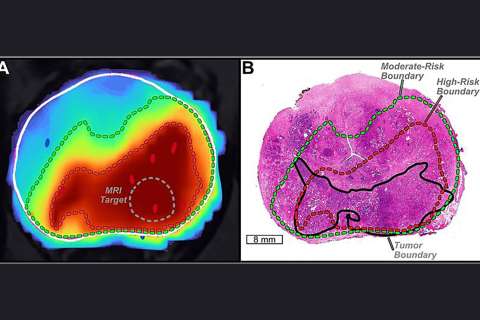

A secondary study finding determined that the drug's efficacy can be monitored quickly using positron emission tomography (PET). Because HIF also regulates glucose transport in cells, UCLA researchers theorized that the kidney cancer cells, with their high levels of HIF, would take in a standard PET imaging probe at high levels. If that proved true, the PET scan would show that the cancer cells had increased levels of the probe. Using laboratory animals, researchers determined that kidney cancer cells were indeed better at taking up the probe, allowing the cancer cells to be monitored by PET scanning. Just 24 hours after treatment with CCI-779, intake of the PET probe levels dropped in the cancer cells, meaning HIF levels were falling and the drug was working.

"If we can use PET scanning to follow response, patients won't need repeated invasive tests," Thomas said. "This would save them from getting an added surgical procedure. And we can see, in a very short time, probably in less than a week, whether the drug is working."

The study was a collaboration of researchers from the Jonsson Cancer Center, the Crump Institute for Molecular Imaging, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the UCLA departments of pathology, urology, medicine and molecular and medical pharmacology.