Each year, about 15,000 children and adolescents in the United States receive the terrifying diagnosis that they have cancer.

The vast majority – about 85% – will survive, thanks to dramatic improvements in treatment over the last several decades. But with that comes another challenge: meeting the need for longer-term follow-up, to address the wide range of issues survivors may face either as a result of their cancer or the specific treatment they received.

That’s where UCLA’s Pediatric and Adolescent Survivorship Clinic comes in.

When Jacqueline Casillas, MD, a pediatric oncologist, founded the clinic 20 years ago, the number of survivors was much smaller, and having a clinic dedicated to meeting their long-term needs was a new concept.

Now, though, there are about 500,000 survivors of pediatric, adolescent and young-adult cancers, according to data from the National Cancer Institute’s Childhood Cancer Registry. The focus has expanded beyond keeping patients from succumbing to their initial cancer to tracking and addressing related issues that may emerge even many years later, from secondary cancers to an increased risk for endocrine disorders or cardiovascular disease.

“We focus on survivors of all sorts of pediatric cancers – anything from neuroblastoma to hepatoblastoma,” said Dr. Casillas, a member of the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. “But we also focus on those that cross into the young adult age group, which includes leukemia, lymphoma, brain tumors, germ cell tumors and sarcomas.”

Patients need to be at least one year past their cancer treatment to receive survivorship care at the clinic, although some are referred there even many years afterward, said Dr. Casillas, who serves as the clinic’s director and is also a professor of pediatrics at in the division of hematology and oncology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

The only other requirement is that their treatment needs to have occurred at some point between childhood and young adulthood. That’s because the issues they face may affect them developmentally and can have ripple effects throughout their lives.

Late effects unique to this population

At the clinic, survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers receive personalized treatment plans to address what are termed “late effects”: a broad category that can include secondary cancers as well as various psychosocial effects such as mental health issues or learning difficulties.

Chemotherapy and radiation can have an effect on the heart and lungs, Dr. Casillas noted, and there are heightened risks for various secondary cancers. Patients diagnosed with cancer during their youth also face increased risks for accelerated aging, such as decreased cardiovascular function or an increase in frailty, much sooner than is typical. “We’re actually seeing that the aging process is sped up,” Dr. Casillas said.

Not only have these late effects become more apparent now that there are far more survivors of childhood cancers, the treatment protocols continue to evolve as well. One example: A new study showed that a blood pressure medication can help protect against heart damage caused by doxorubicin, a widely used chemotherapy drug.

Patients may also have challenges such as learning difficulties as a result of radiation therapy, or may need help navigating school issues such as returning to college or requesting accommodations such as additional time for test-taking.

“We know specifically which late effects you’re at risk for, because it’s very targeted based on your individual cancer treatment,” said Dr. Casillas. “Even if you had the same diagnosis as someone else, you may not have gotten the same treatment. That’s why this clinic is critical, because it provides a specific plan based on your treatment history.”

While treatment for cancer can be considered a traumatic life event, she noted, it can be even more so for a young person who may be grappling with body image issues, such as coping with baldness, or worrying about potential future impact on their fertility.

Keeping patients from getting lost in transition

Undergoing cancer treatment can be overwhelming, but once it ends, patients can feel unmoored.

“Some people have described going through chemo as kind of like a safety net,” Dr. Casillas said, given the all-encompassing nature of frequent treatments such as chemotherapy, blood transfusions and radiation. But afterward, patients may not even know what questions to ask about potential future issues, or may wonder if various symptoms they’re experiencing are related to their cancer treatment.

Survivorship care bridges that gap, Dr. Casillas explained. Even though patients will typically be followed by their oncologist for a period of time and will likely have a primary care provider as well, neither specializes in the wide range of survivorship issues, including the need for additional late effects screenings (or earlier cancer screenings) based on the patient’s cancer treatment history.

Although patients treated at freestanding children’s hospitals may be receiving survivorship care there, it typically ends once they turn 21 and reach the age cutoff.

At UCLA, though, which provides both pediatric and adult care, there’s no such cutoff. “We’re able to provide care across the age continuum from childhood through adulthood,” Dr. Casillas said. “We have the ability to provide care without an end date, and that’s very unique.”

Patients may be referred from other treatment centers or from within UCLA Health, and some patients are even referred from adult oncologists treating survivors of childhood cancers. What matters is the age at which the cancer was diagnosed, not the age of the patient or even the specific prognosis, Dr. Casillas said.

“We may have patients who have a brain tumor who are now being followed by the neuro-oncology team, but they have specific survivorship needs. We are not diagnostic specific in the sense that we are doing these survivorship care plans based on an individual’s treatment, not necessarily on their diagnosis,” she said.

In addition to Dr. Casillas, the clinic includes a nurse practitioner who helps patients navigate referrals, an education specialist who helps with learning and school-related issues, and a robust referral network of various specialists, including cardio oncologists.

“We refer within UCLA Health to targeted multidisciplinary providers to help care for our patients when they have specific late effects,” Dr. Casillas said.

Spreading awareness about survivorship care

Although patients don’t start receiving care at the clinic until at least one year after their treatment ends, the goal is to educate them about the need for survivorship care much earlier than that, Dr. Casillas said, to empower them to be “active consumers in their survivorship care.”

That’s currently being done via text-messaging-based outreach to the clinic’s patients, but she hopes to expand the audience by working with pediatric oncology departments to identify patients and sign them up right when they finish treatment.

“We want to bring survivorship care to where the survivor is,” Dr. Casillas said. “There can be a lot of missed opportunities for needed survivorship care screening as they move into adulthood,” she explained. “It might have been the parent driving the care, or they moved out of state and are no longer connected to their cancer center.”

Patients are prompted via text to select their top three goals, then directed to additional recommended steps and resources. They also receive follow-up calls to help them navigate through issues such as insurance roadblocks or delays in getting a referral to a survivorship doctor.

Not only does the text-messaging outreach distill down what can be an overwhelming amount of information into an accessible format, she noted, it also increases the likelihood that patients will seek out survivorship care, which in turn helps improve their long-term outcomes.

"Right now we are focusing on the young adult patients and have not yet done it with parents," Dr. Casillas said, "but that is phase 2 of the research, to start reaching out to parents and younger teens.”

Targeted outreach for Latino survivors

Reaching out to survivors in a way that’s effective also means doing so in a way that’s culturally relevant, Dr. Casillas noted. “We know that having more culturally targeted communications and understanding the unique needs of our diverse populations are critically important.”

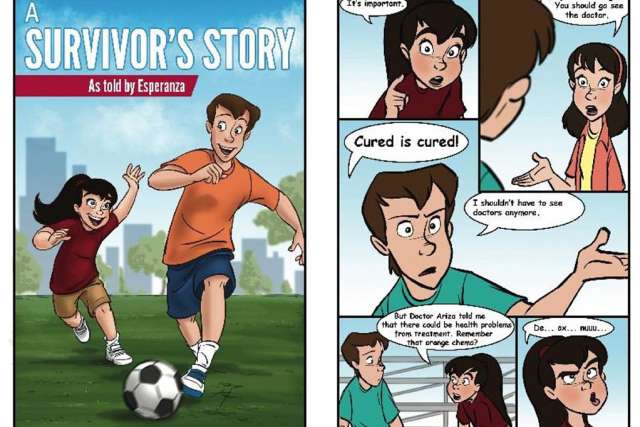

Because more than half of the clinic’s patients are Latino, she recently created a fotonovela (a photo-based booklet with text bubbles for dialogue) in both Spanish and English. The booklet was funded via a grant from the National Cancer Institute and developed with input from local community members, including an advisory group of survivors and their families.

“We know that within our Latino community, the importance of family is so critical,” Dr. Casillas said, “so when we wrote the booklet, we took a family-centered approach.”

The story is told through the lens of a young teenager who’s a cancer survivor and wants to play soccer. “It integrates the family, and it also integrates the discussion with the doctor,” she explained. “Many times, people don’t want to challenge their doctor or ask them for things. We’re trying to educate them that yes, it’s OK to ask your doctor for a survivorship care plan.”

The fotonovela also addresses health insurance, which can be a “big barrier,” for teens and young adults, Dr. Casillas said. “Health insurance literacy isn’t easy for anybody,” she pointed out.

Although fotonovelas have previously been used in other health contexts, such as diabetes educational outreach, they hadn’t yet been used for reaching cancer survivors. But it was a format that made sense for this audience, she noted.

“We knew the key survivorship messages to convey to help change health behaviors. The goal is to help ensure “they’ll get that needed care,” Dr. Casillas explained, “versus ‘I don’t want to deal with it, because I’m too scared.’”

The booklet is available in print and in an electronic format.

“We’ve taken these national educational tools that are very dense and wordy and made them understandable for teens and young adults and their family members,” Dr. Casillas said. They’re still getting the same health messages, she noted, but in a more accessible and relevant format.

Above all, Dr. Casillas said, “we want it to be a hopeful message."

“Because the whole thing with survivorship care and late effects is that if we know that something could be a risk, we can screen for it,” she said. “And if you do develop it, we can pick it up early enough so that it’s not a big health risk.”

Lisa L. Lewis is the author of this article.