Photo: U.S. Army Specialist E-4 Manuel Umana with his daughter, Emma. (Photo courtesy of Jacqueline Ochoa)

When Manuel Umana left Southern California for basic training at U.S. Army Installation Fort Jackson in South Carolina, he was excited — albeit nervous — about becoming a new father. He dreamed of the day he could return home to hold his baby girl, breathing in her sweet scent.

Imagine his angst several months later when he learned his infant daughter, Emma, whom he had yet to meet, would need surgery to correct a congenital heart defect.

“It was a little bit of a roller coaster on my end,” recalls Umana, Specialist E-4, now a calibrator in the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg Army Base in Fayetteville, N.C. “One, we don’t know the first thing about having a child and then, two, finding out your child has some kind of a heart condition — that threw me for a loop.”

Emma Umana, now 21 months old, was born with ventricular septal defect (VSD), a condition in which a hole in the wall (septum) separates the two lower chambers (ventricles) of the heart. The defect occurs during pregnancy if the wall between the two chambers does not fully develop, leaving a hole.

If the hole is large, as Emma’s was, the infant might experience shortness of breath, fast or heavy breathing, sweating, fatigue while feeding, or fail to gain weight or thrive.

A majority of VSDs are detected at birth; however, Emma’s was detected at 4 months, during her first pediatrician visit after the family switched from another hospital system to UCLA Health.

“I was very surprised,” says Jacqueline Ochoa, Emma’s mom. “And I was scared because it happened so quickly. We saw her pediatrician and then we get hit with ‘She has a heart murmur’ and ‘We can get her in the cardiac unit later today.’”

Ochoa was instructed to take Emma to Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, where an echocardiogram confirmed Emma had a 10-millimeter apical muscular VSD.

Alone, with Emma’s dad by then stationed at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., Ochoa felt lost.

“I was a mess. I was scared, crying,” she says. “I didn’t know what to do.”

Rare procedure

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 1 in every 240 babies in the U.S. each year is born with a ventricular septal defect. Many VSDs are small and close on their own, over time. However, the size of Emma’s made surgical closure necessary.

To further complicate matters, Emma’s VSD was different in shape and location than most, says Gregory Perens, MD, professor in the Division of Pediatric Cardiology at UCLA Health.

“Hers was a very unique VSD that had an odd shape and some extra muscle around it on the left side of her heart that tunneled in a snake-like shape through the wall and came out on the right side,” Dr. Perens says. “That made the defect difficult to understand on the two-dimensional pictures from the ultrasound.”

Given the characteristics of her VSD, Emma’s care team chose to use a “hybrid” surgical and interventional catheter technique in which the chest is opened and a catheter is placed directly into the heart to deploy a special closure device into the VSD hole.

“I would say the procedure is relatively rare,” Dr. Perens says. “Even at UCLA Health, where our surgeons and catheter doctors are always looking at options, it’s only been done three or four times on babies under a year of age.”

Modeling innovation

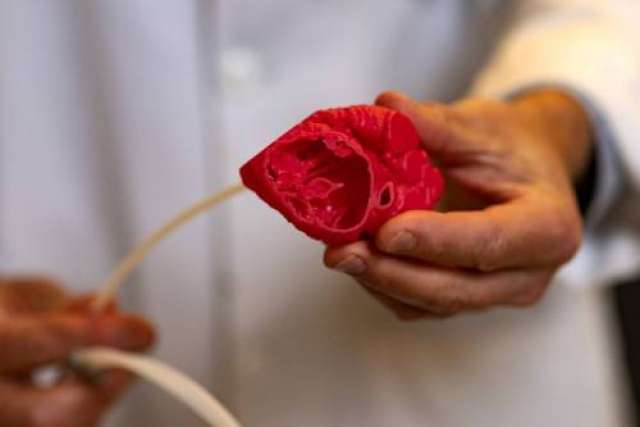

Ahead of the surgery, a 3D model of Emma’s heart was produced from a CT scan using a 3D printer to lay down polymer in a representative form of her heart. This model enhanced the understanding and visualization of the patient’s anatomy and allowed for a risk-free environment to rehearse the procedure, Dr. Perens says.

The finished model was given to the catheter doctor, Daniel Levi, MD, an interventional pediatric cardiologist at UCLA Health, and the surgeon, Glen Van Arsdell, MD, chief of congenital cardiac surgery at UCLA Health, to mimic what would happen during Emma’s surgery.

“With this model, you can determine where the catheter will go and what size device will go in there,” Dr. Perens says. “You can simulate what putting that device in the heart will be like and make sure it looks good. And we thought it looked good.”

Ashley Prosper, MD, a radiologist specializing in thoracic and diagnostic cardiovascular imaging at UCLA Health, notes the use of 3D printers in health care settings has expanded in recent years as they have become more readily available.

She lauds the benefits of using 3D models for pediatric heart surgeries.

“It’s one thing to see something on a 2D or even a 3D computer rendering, but it’s another to be able to actually hold it. You can see the surface rendering and then you can flip it around and see what the inside looks like,” says Dr. Prosper, who, along with Takegawa Yoshida, MD, a research associate in the Department of Radiology, collaborates with Dr. Perens on producing the 3D prints.

An in-house grant from UCLA Children’s Heart Center and encouragement from Dr. Van Arsdell have helped further the use of 3D models, Dr. Perens notes.

“He’s probably the biggest proponent for using 3D models for teaching and planning. A lot of this inspiration comes from him.”

First meeting

Emma’s surgery was scheduled for Dec. 17, 2020. Umana was counting on being by his daughter’s side, but the military had other ideas — his holiday leave wouldn’t begin until Dec. 20. When they learned this, Dr. Perens and his assistant jumped into action and sent an emergency Red Cross alert to his base to bring him home five days sooner.

“That’s why I was able to fly down and be present for the surgery,” Umana explains. “It was a weird situation: You meet your child for the first time and then two days later she’s in OR. It was definitely stressful.”

Due to COVID-19 protocols, neither parent was allowed to be at the hospital during Emma’s surgery. Instead, they waited at home where they received text updates.

“We were in a system where they would text us throughout the whole procedure,” Ochoa says. “I think the prep time was maybe two or three hours and the actual surgery was under an hour.”

Emma is thriving

Emma went home three days after surgery. Now, 15 months post-surgery, she is continuing to thrive, Dr. Perens says.

“She’s so resilient,” Ochoa says. “The first day at the hospital was a little tough; I could tell she was in pain. But the next day she was watching Elmo on her iPad, kicking up her little feet. By the time she went home she was back to herself.”

Both Umana and Ochoa say throughout the process, the nurses and doctors at UCLA Health were outstanding.

“Dr. Perens communicated so well with us,” says Umana, who is in North Carolina awaiting possible deployment to Poland. “I’m sure he has a billion things to do every day, but he responds every single time, even to this day, so that just makes us feel a lot more secure. We could tell that he cares about what he does, and we really appreciate that. There are no words to describe the caliber of physician he is.”

Umana advises parents facing similar surgery at UCLA Health to trust the staff and the process. “We were really afraid, and it’s OK to be concerned, it’s OK to be worried. But you’re definitely in good hands.”

Learn more about the UCLA Congenital Heart 3D Printing Program.

Jennifer Karmarkar is the author of this article.