Cure rates are high for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common childhood cancer. But for the 10% to 15% of these patients who relapse or continue to experience progressive disease after treatment, and for children with relapsed, treatment-refractory lymphoma, the best opportunity for cure has been a bone marrow transplant (BMT).

However, the procedure comes with significant morbidity and mortality. Moreover, BMT has a low success rate if performed while the patient has active disease.

“You really have to obtain a remission first,” says Theodore Moore, MD, chief of pediatric hematology/oncology at UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital and director of the UCLA Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Program. “And in the past, when that wasn’t possible, there wasn’t a great deal that we could offer.”

That calculus has shifted dramatically with the advent of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, a form of immunotherapy that Dr. Moore calls a “game-changer” for the treatment of relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia and relapsed/refractory lymphoma.

“For many patients, this treatment is able to obtain remission so that they can move forward with the bone marrow transplant,” says Dr. Moore, a member of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. “And for some, the CAR T cells have been enough to produce a sustained remission without the need for a transplant.”

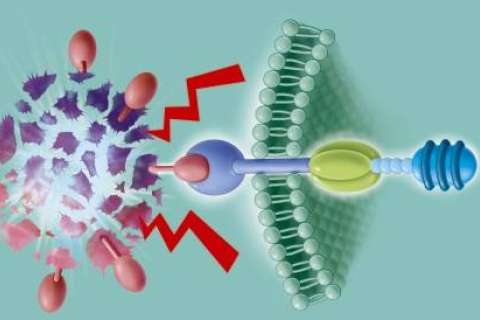

Immunotherapies hold great promise for their ability to program the patient’s immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells, making the therapy more specific and less toxic than traditional radiation and chemotherapy, which go after cells indiscriminately. These approaches include molecules — most notably checkpoint inhibitors, which have been approved to treat a host of cancers — that help the body’s immune system unmask and attack cancers.

CAR T-cell therapy falls under the category of cellular therapies — harnessing the cells within the body. The first hint that cellular therapy could be useful against cancer came in the early years of bone marrow transplants, Dr. Moore notes.

“With bone marrow transplants, you’re trying to find a perfect match,” he says. “But we learned that although an identical twin offered the best donor match, the rate of relapse actually went down when you had a nonidentical sibling, and it was even less than that with an unrelated donor. The more different the immune-system cells were when they went into a new body, the more likely they were to recognize differences and have an effect, leading researchers to ask whether we could take a person’s own cells and engineer them to go after the cancer.”

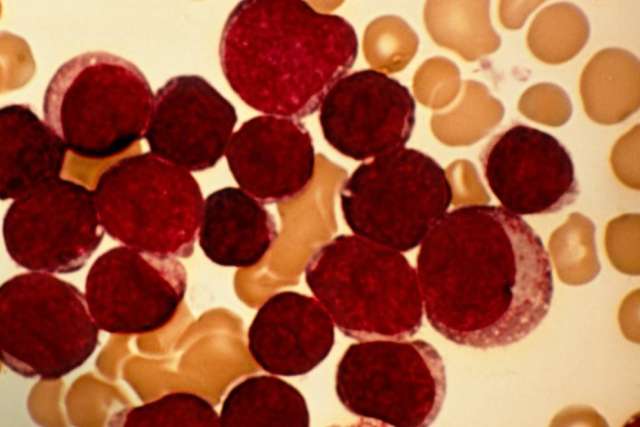

In CAR T-cell therapy, T cells — the central components of the immune system — are collected from the patient’s blood, then engineered in the laboratory so they can recognize and attack certain blood cancers. The modified cells are then returned to the patient’s body. If the treatment is successful, the newly modified T cells help the patient’s immune system kill off cancer cells, sending the disease into remission. In 2018, UCLA Health became one of the first health systems in the nation to offer commercial CAR T-cell therapy in clinical trials.

In 2020, UCLA Health was among the first to offer U.S. Food & Drug Administratio-approved CAR T-cell therapy to treat relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma.

Prognostic factors that help determine whether patients should go on to a transplant after CAR T-cell therapy include an analysis of how well the CAR T cells are functioning in the body, as well as the previous resistance of the patient’s disease, Dr. Moore explains.

While CAR T-cell therapy approved for pediatric patients with relapsed leukemia and relapsed/refractory lymphoma, Dr. Moore and his colleagues are currently participating in a Children’s Oncology Group protocol asking if patients identified as high risk for

relapse should be treated with engineered CAR T cells prior to any relapse, lessening the need for additional chemotherapy and potentially preventing the need for a bone marrow transplant in these patients.

Learn more about CAR T-cell therapy at UCLA Health.

Dan Gordon is the author of this article.