Breast Anatomy

by Parsa Asachi, MD, Lucy Chow, MD, and Bo Li, MD

Introduction to Breast Anatomy

The breasts are glandular organs that play an important role in providing nutrients for developing infants and can succumb to various pathological diseases such as breast cancer. Understanding the anatomy of the breast is crucial for diagnostic breast imaging and surgical procedures.

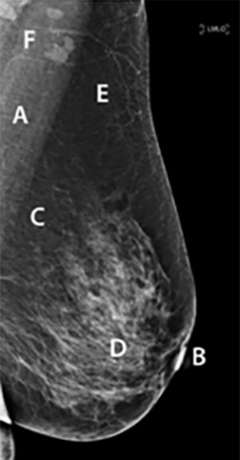

The breasts extend from the second to sixth rib and are anchored to the pectoralis major fascia via the Cooper ligaments1. As the breasts mature and sag due to the stretching of the Cooper ligaments, they can further extend below the sixth rib. Horizontally, the breast extends from the side of the sternum to the midaxillary line, where the tail segment of breast tissue called the axillary tail of Spence resides2. The nipple is commonly located in the center of the breast, superior to the inframammary crease (the inferior fold made by the breast tissue), lateral to the midclavicular line, and at the level of the fourth rib1. The areola is a hyperpigmented, ovular area of skin that concentrically surrounds the nipple3. The nipple and areola together are referred to as the nipple areola complex (NAC), an anatomical classification important in surgical procedures such as mastectomies4. Posterior to the areola is the retro-areolar region, which appears as a triangular-shaped zone in mammograms and can potentially hide breast tumors5. The breast contains the mammary gland, which produces milk that is secreted through outlets in the nipple. The mammary gland is made up of glandular, adipose, and fibrous tissue.

Glandular Structures

Each breast contains around 15-20 lobes surrounding the nipple in a radial pattern1. The lobes are comprised of lobules, which contain the alveolar clusters that produce milk through mammary secretory epithelial cells6. Each alveolar cluster is attached to a small duct, which drain into larger ducts and eventually the main duct for that lobe. This lobular duct then widens into a lactiferous sinus, narrows at the base of the nipple, and terminates at the surface of the nipple7. The terminal duct and lobule pairing is referred to as the Terminal Ductal Lobular Unit (TDLU). Although not visible in imaging, most breast cancers arise from TDLUs2. The glands appear radiopaque on mammograms3.

Stroma

Adipose and dense fibrous tissue are interspersed between the lobes and around the breast1,3. The stroma in which these tissues occupy are divided into three regions: the subcutaneous part between the skin and gland, the intraparenchymal portion lying between the lobes and lobules, and the retromammary portion which is located behind the gland3. Cooper’s ligaments arise from the superficial layer of the subcutaneous superficial fascia and are suspensory ligaments that provide structural support to the parenchyma3. On mammographic imaging, the adipose tissue is radiolucent while the stroma appears radiopaque3.

Arterial supply

The blood supply to the medial aspect of the breasts are the internal mammary arteries, supplied by the internal thoracic arteries traveling along the inner surface of the anterior chest wall bilaterally. The internal thoracic arteries are supplied by the subclavian arteries. The lateral aspect of the breast is supplied by the lateral thoracic and thoracoacromial branches of the axillary artery, lateral mammary branches from the posterior intercostal arteries, and the mammary branch of the anterior intercostal artery. The blood vessels appear as thin, tortuous, linear opacities in mammograms and are more visible in breasts containing more adipose tissue3,8,9.

Venous drainage

The venous drainage of the breast is divided into the superficial and deep veins. The superficial veins form the venous plexus of Haller, which runs deep to the nipple areolar complex and along the anterior surface of the fascia. The deep veins run along with the arterial supply of their respective region. They eventually drain into the internal mammary and axillary veins1,9.

Associated Muscles

As mentioned previously, the breast mainly sits anterior to the pectoralis major fascia and muscle. In mammograms, the pectoralis major muscle can be seen as a slightly radiopaque, linear structure located posterior to the breast tissue3. The sternalis muscle is a bandlike structure that runs longitudinally along the medial border of the sternum, bulging anteriorly as the patient is placed in the decubitus position and relaxes the muscle10. The sternalis muscle can be most clearly seen in the craniocaudal projection in mammograms as an irregular opaque body located medially to the breast10. Laterally, the external oblique muscle runs along the inferolateral edge of the breast while the rectus abdominis establishes the inferior border of the breast. Moreover, the serratus anterior runs along the lateral aspect of the chest wall and breast1.

Nervous supply

The breast is supplied by the anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of the 4th through 6th intercostal nerves, which contain both sensory and autonomic nerve fibers. The lower cervical plexus also supplies some sensory innervation to the breast. The nipple areola complex is innervated by sensory nerves from the lateral cutaneous branch of T41,9.

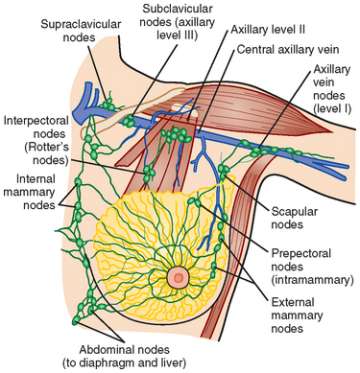

Lymphatic drainage

The three lymph nodes groups that lymph from breast tissue drain into are the axillary nodes, parasternal/internal mammary nodes, and supraclavicular nodes. Most of the lymph flows into the axillary nodes, which serves the lateral quadrants of the breast and are divided into three levels, depending on the location11. Level I axillary lymph nodes contain three groups of lymph nodes and are located inferolateral to the pectoralis minor muscle. Level II axillary nodes, on the other hand, contain only one group and are located directly posterior to the pectoralis minor. Lastly, level III axillary lymph nodes have one group and are located superomedial to the pectoralis minor. Axillary lymph nodes are best denoted on MRI imaging, but can sometimes be seen on medio-lateral-oblique (MLO) mammograms. In instances where abnormalities are found in axillary lymph nodes, knowing which levels are affected is important for planning the subsequent treatment plan12,13. The superficial lymphatic vessels include the areolar and subareolar (Sappey’s) plexus, which drain lymph from the nipple, areola, and some glandular tissue eventually into the axillary nodes9. Lymphatic vessels draining lymph from the lateral and medial quadrants of the breast eventually lead to the internal mammary lymph nodes after passing through intercostal spaces and the pectoralis major muscle11. The internal mammary nodes are located immediately medial to the breast tissue and are not typically seen on mammograms. The intramammary lymph nodes are located in the upper outer quadrant of the breast tissue and are typically seen in craniocaudal (CC) mammograms14.

Sources:

- Rivard AB, Galarza-Paez L, Peterson DC. “Anatomy, Thorax, Breast.” In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519575/

- Overview of the Breast - Breast Pathology | Johns Hopkins Pathology. Johns Hopkins Medicine, Pathology. Published 2021. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://pathology.jhu.edu/breast/overview

- De Benedetto D, Abdulcadir D, Giannotti E, Nori J, Vanzi E, Capaccioli L. “Radiological anatomy of the breast.” Ital J Anat Embryol. 2016;Vol 121:20-36 Pages, 1010 kB. doi:10.13128/IJAE-18341

- Zucca-Matthes G, Urban C, Vallejo A. “Anatomy of the nipple and breast ducts.“ Gland Surg. 2016;5(1):32-36. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2015.05.10

- “Mammography: Guide to Interpreting, Reporting and Auditing Mammographic Images.” Radiology. 2006;240(2):334-334. doi:10.1148/radiol.2402062569

- Tobon H, Salazar H. “Ultrastructure of the human mammary gland. II. Postpartum lactogenesis.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1975;40(5):834-844. doi:10.1210/jcem-40-5-834

- Vorherr H. The Breast: Morphology, Physiology, and Lactation. Elsevier; 2012. https://books.google.com/books?id=wYxirvD2X2IC&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- Shahoud JS, Kerndt CC, Burns B. “Anatomy, Thorax, Internal Mammary (Internal Thoracic) Arteries.” In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537337/

- Kammath V. The Breasts - Structure - Vasculature - TeachMeAnatomy. Published September 22, 2021. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://teachmeanatomy.info/thorax/organs/breasts/

- Bradley FM, Hoover HC, Hulka CA, et al. “The sternalis muscle: an unusual normal finding seen on mammography.” Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166(1):33-36. doi:10.2214/ajr.166.1.8571900

- Pacifici S. Lymphatic drainage of the breast | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org. Radiopaedia. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/lymphatic-drainage-of-the-breast?lang=us

- Cao MM, Hoyt AC, Bassett LW. “Mammographic Signs of Systemic Disease.” RadioGraphics. 2011;31(4):1085-1100. doi:10.1148/rg.314105205

- Ecanow JS, Abe H, Newstead GM, Ecanow DB, Jeske JM. “Axillary Staging of Breast Cancer: What the Radiologist Should Know.” RadioGraphics. 2013;33(6):1589-1612. doi:10.1148/rg.336125060

- Bitencourt AG, Ferreira EV, Bastos DC, et al. “Intramammary lymph nodes: normal and abnormal multimodality imaging features.” Br J Radiol. 2019;92(1103):20190517. doi:10.1259/bjr.20190517