Thyroid Nodules & Thyroid Cancer

Find your care

We deliver effective, minimally invasive treatments in a caring environment. Call 310-267-7838 to connect with an expert in endocrine surgery.

Related Videos

You may also like:

What Are Thyroid Nodules?

Thyroid nodules are lumps or growths of the thyroid, usually made up of normal thyroid tissue or fluid. Thyroid nodules are frequently discovered on routine physical examination or unintentionally on imaging tests.

By the age 45, up to half of normal people have thyroid nodules that can be seen on an ultrasound. Fortunately, about 95% of thyroid nodules are benign. The focus of the evaluation at the UCLA Endocrine Center is to help you determine if your nodule contains cancer or not.

Thyroid Nodules Symptoms

Most thyroid nodules do not cause any symptoms. Some thyroid nodules show up as a painless lump in the neck that you can feel or see. Thyroid nodules usually move up and down with swallowing.

What Causes Thyroid Nodules? Hello, I'm James Wu, an endocrine surgeon with the UCLA Health Endocrine Center. One common question I receive is about the causes of thyroid nodules.

When thyroid nodules become large (>4 cm or 1.5 in) they may cause symptoms by pressing on the airway or esophagus. These are also called “compressive symptoms.” Compressive symptoms include:

- Discomfort with swallowing

- Discomfort when lying down in certain positions

- A tight feeling when wearing a collared shirt

- Noisy breathing at night

- Food getting stuck in the throat

- Shortness of breath when exercising and difficulty breathing.

Sometimes thyroid nodules can produce excess thyroid hormone. Excess thyroid hormone, also called hyperthyroidism, can cause the following signs and symptoms:

- Heat intolerance (feeling hot when others do not)

- Fatigue

- Anxiety or swings in emotions/mood

- Weakness

- Tremor

- Palpitations or feeling of an irregular heartbeat

- Increased sweating

- Weight loss despite normal or increased appetite

- Thinning hair

How Are Thyroid Nodules Evaluated?

At the UCLA Endocrine Center in Los Angeles, multiple layers of evaluation are designed to help you avoid invasive tests and surgery whenever possible. Consultation, ultrasound, and FNA can all be performed in a single visit.

Initial evaluation of a newly discovered thyroid nodule begins with:

- Assessment by an endocrinologist or endocrine surgeon

- Thyroid function tests (laboratory tests)

- Neck ultrasound performed by your doctor

An ultrasound is a highly accurate tool to visualize your thyroid nodule. There is no associated radiation with ultrasounds and it is non-invasive. Ultrasounds are cost-effective as most patients really don't need any other imaging because the ultrasounds are the best way to look at the thyroid, all present nodules, and the lymph nodes in the neck.

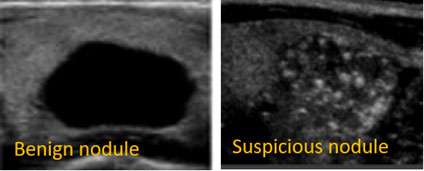

Not all thyroid nodules need a biopsy. For many thyroid nodules we see in our office, we choose not to biopsy because the ultrasound appearance is so reassuring. That is one way to avoid over treatment. For example, nodules that appear completely black on the inside (“anechoic”) are purely cystic, or filled with fluid. The chance of thyroid cancer for a cystic nodule is essentially zero and cystic nodules do not require biopsy. There are guidelines from the American Thyroid Association that will help your doctor determine which nodules to biopsy based on their size and how suspicious they look on the ultrasound.

There are certain factors that make a nodule suspicious for thyroid cancer. For example, nodules that do not have smooth borders or have little bright white spots (micro-calcifications) on the ultrasound would make your doctor suspicious that there is a thyroid cancer present. If the nodule appears suspicious on ultrasound and is larger than 1cm, the next step is to do a thyroid biopsy.

Our cytopathologists evaluate over 1000 samples per year, so we are confident in the accuracy of our biopsies. When biopsy does not give a clear answer, we automatically use molecular profiling to refine the diagnosis.

How Is a Thyroid Biopsy Performed?

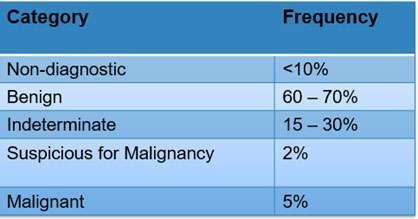

A thyroid biopsy, also called a fine needle aspiration (FNA), uses a small needle to take a little sample of the cells in the thyroid nodule. The possible outcomes from a biopsy are:

Non-diagnostic: Non-diagnostic is a technically failed biopsy. There were not enough cells taken during the biopsy so the cytologist was not able to determine anything. These usually need to be repeated.

Benign: Most thyroid nodule biopsies come back benign, meaning your doctor is highly re-assured that it's not cancerous. Patients can almost always avoid surgery unless the nodule is large and pushing on adjacent structures like the airway.

Indeterminate: Indeterminate means there was enough cells taken during the biopsy, but the cytopathologist was not sure if it is benign or malignant. Indeterminate results occur in about 20% of thyroid biopsies. This is a gray zone and means that the risk of cancer is about 10-30%. These nodules require additional work-up such as a repeat biopsy, molecular marker test, or surgical removal.

Suspicious for Malignancy or Malignant: Results categorized in these two categories are a strong indicator that there is thyroid cancer present and usually require surgical removal.

Patients usually wait one week for the cytopathologist to examine the cellular characteristic of the biopsy sample. If your doctor is reassured that it's benign based on the biopsy result, further work-up is stopped and serial ultrasound surveillance is recommended usually once a year.

What Is Molecular Profiling?

At UCLA, thyroid nodules with indeterminate biopsies are sent out for an additional molecular marker test. An “indeterminate” biopsy result is the gray zone where the risk of thyroid cancer is intermediate (10–30%) but cannot be ignored.

Sometimes the biopsy result is reported as “indeterminate.” This means the cells are not normal, but there are not definite signs of cancer. When biopsies are indeterminate, the risk of thyroid cancer is 15–30%. Learn about molecular profiling.

Thyroid Nodules Diagnosis

In the past, to avoid missing a cancer, we recommended thyroid lobectomy (removal of half of the thyroid) to establish a definitive diagnosis. Now, we use molecular profiling. This refers to commercial DNA or RNA tests made specifically for indeterminate thyroid nodules. If the genetic profile appears benign, patients can avoid surgery and we simply watch the nodule over time with neck ultrasound.

Thyroid Molecular Markers Allow Patients to Avoid Surgery

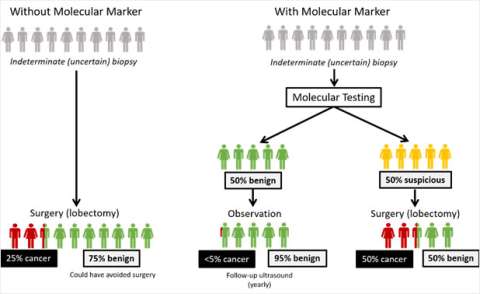

We want to help patients find that perfect balance between under-treatment and over-treatment. The people-gram shows how molecular testing can help patients avoid unnecessary surgery.

Left Path: Before the use of molecular markers, everyone with an indeterminate biopsy went to surgery. Of those who went to surgery, thyroid cancer was found in only 25% of those cases (red). 75% of the surgical patients turned out not to have needed surgery at all because their nodules were benign (green).

Right Path: Today, if you have an indeterminate biopsy, you also undergo molecular testing. 50% of patients (green) were categorized as benign from the molecular test and safely avoided surgery. Of the surgical patients who received a suspicious molecular test result (yellow), cancer was found in 50% of those patients (red).

It is very rare that patients end up having thyroid cancer because of a false negative test. Still, it is UCLA’s standard of care to have a safety net and follow every patient after molecular testing, regardless of their result. Those patients will get ultrasounds every 12 months to ensure that nodules do not grow or change in appearance.

What Are the Possible Causes of a Thyroid Nodule?

Thyroid Adenoma

Thyroid adenomas come in different forms and have different names, but they are benign growths of normal thyroid tissue. These do not require treatment if they are not causing compressive symptoms. If they are not causing symptoms, most of these are watched with neck ultrasound.

Toxic Adenoma

Toxic adenomas are thyroid adenomas that secrete excess thyroid hormone.

Thyroid Cysts

Thyroid cysts are fluid-filled nodules within the thyroid. Pure thyroid cysts are usually benign (non-cancerous).

Goiter

Any enlargement of the thyroid gland is referred to as a “goiter.” Goiter can be caused by Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis (an autoimmune disease) and iodine deficiency. These do not require treatment unless the goiter is causing compressive or hyperthyroid symptoms.

Multinodular Goiter

A multinodular goiter is an enlarged thyroid gland containing multiple nodules. Most often, these nodules are benign. As above, these only require treatment if you are experiencing compressive or hyperthyroid symptoms, or if one or more of the nodules is suspicious for thyroid cancer.

At UCLA Health, we are proud to offer radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for the treatment of a number of thyroid conditions.

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) at UCLA

The UCLA Thyroid RFA Program is a collaboration between UCLA interventional radiology, endocrinology, and endocrine surgery to provide this state-of-the-art treatment to our patients.

Our endocrine surgeons, Dr. James Wu and Dr. Masha Livhits, and our interventional radiologists, Dr. David Lu, Dr. Michael Douek and Dr. Gary Tse have extensive experience in thermal ablation procedures. UCLA performs more than 500 thermal ablation procedures annually in different organs throughout the body.

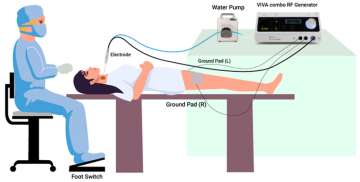

What is RFA?

RFA is a minimally invasive treatment option performed by interventional radiology that is an alternative to surgery in some patients with thyroid nodules. During this procedure a small needle electrode is inserted into the thyroid nodule using ultrasound guidance. Heat generated at the needle tip destroys the target tissue. Learn more about Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) at UCLA.

Find your care

We deliver effective, minimally invasive treatments in a caring environment.

Call 310-267-7838 to connect with an expert in endocrine surgery.