Is depression statistically measurable? How about anxiety?

For years, the answer would have been no, presenting a challenge for behavioral health specialists in tracking long-term improvement among their patients.

But then came measurement-based care, or MBC.

“Measurement-based care is exactly what it sounds like – it’s basing psychiatric care off of measurements,” says Carl Fleisher, MD, child and adolescent psychiatrist at UCLA Health. “There was a time when people thought you couldn’t measure it because it is emotions or you can’t measure it because it is relationships, but you can measure anything.”

Dr. Fleisher said using questionnaires and grading scales to measure people’s mental state can be helpful when working with a patient. Doing so allows clinicians to track a patient’s mental state over time and allows them to compare to other cases.

“People think, ‘If I fill out this form, it’s not really helping’ or ‘It’s not helping because you can’t measure depression on a piece of paper.’ But that’s not the point,” Dr. Fleisher said. “The point is to be able to measure change.”

Dr. Fleisher said that being able to rate a patient at a beginning point of care and then track the patient’s rating over several months – monitoring its ebb and flow – is beneficial for both clinician and patient.

Measurement tools for psychiatry

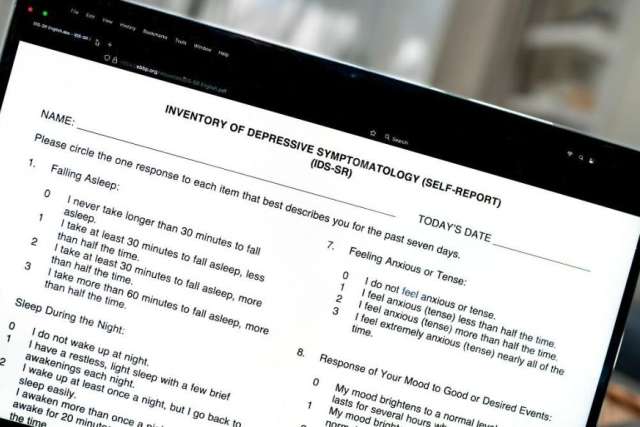

Two popular instruments used to measure psychiatric progress are the Inventory of Depressive Symptomology (IDS) rating scale and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomology (QIDS). Results are measured by tallying the scores assigned to responses to multiple questions.

IDS is a 30-item rating scale used to identify depressive symptoms as defined by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). It has been used by psychiatrists as a behavioral health evaluation tool and has been administered to patients to establish a baseline.

The survey measures nine areas including quality of mood, concentration/decision-making, personal outlook, thoughts of death or suicide, involvement in life, energy level, sleep, appetite/weight change and agitation

The QIDS evaluation tool is a shortened version of the IDS. Instead of 30 questions, it was developed as a 16-item assessment. QIDS and IDS tools can be used interchangeably for patients based on the physician’s determination.

With either technique, clinicians and their patients are able to chart the nummerical results of the survey and determine where a patient is mentally and what help they may need to get better.

“The numbers can get integrated into a chart for sure and then we can look at it with our patient and say, for instance, ‘Today was a 12, and three months ago you were at a 27, so look how much better that is,” Dr. Fleisher said.

“With each grading scale, it’s not something that is made up on the spot. It’s not subjective or unique to that person. It’s like if you’re a 27, that’s moderate. If you’re at a 38 that’s severe and we want to get you to a 12 because that means you’re functioning at a normal level and that means you’re better.”

There are other commonly used clinician rating surveys, but not all of them measure all nine of the areas defined by the APA.

How does measurement-based care work?

There are four components to measurement-based care as it relates to behavioral health:

- A measurement process: The patient fills out the survey form (such as IDS or QIDS) so both the patient and clinician have statistical data for comparison.

- Practitioner review of data: The clinician looks over the answers and tallies the score to determine the patient’s behavioral health status.

- Patient review of data: The clinician reviews the score with the patient.

- Collaborative reevaluation of the treatment plan informed by data: The clinician and patient decide what the data means and work toward possible solutions.

Emanuel Maidenberg, PhD, clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, says MBC helps practitioners better track their patients’ health.

“Measurement-based care improves the validity of change metrics by offering more objective, measurable and/or observable tools that allow making comparisons of treatment effectiveness for an individual patient,” Dr. Maidenberg said. “It also allows a comparison to others who have a similar profile or degree of challenges.”

Benefits of rating and tracking progress

Dr. Fleisher’s belief that tracking behavioral progress improves a patient’s chances of recovery is supported by data.

“I was looking at a study recently from a group in China where two groups of adults with major depression were being treated. It turns out that the group whose progress was getting rated, or tracked, got better at a higher percentage,” Dr. Fleisher said. “In the group that had standard care, about 25% got to recovery. The group whose progress was being tracked, about 75% of the patients recovered.”

Dr. Fleisher said that tracking a patient’s progress raises the participation level of the patient. He said measurement-based care promotes accountability from both the clinician and the patient.

“Measurement-based care first puts accountability on the clinician’s side, meaning that if I do my job then you, as the patient, are going to improve,” he said. “You’re going to feel better.”

Sometimes a patient can forget how they were feeling earlier in treatment, he said. Measurement-based care enables them to more easily see progress.

Barriers to implementation

Dr. Fleisher said the main barrier to broader use of MBC tools for behavioral health is simply shifting from traditional methods of care.

“The biggest roadblock to measurement-based care is the providers, and systems that surround providers,” he said. “It’s hard to get large systems to adapt this kind of stuff.”

UCLA began implementing measurement-based care for behavioral health about four years ago.

Dr. Maidenberg added that despite recent criticism of MBC, he feels that moving forward there will be more acceptance as patients and providers continue to see progress.

He said much of the criticism has to do with an under-appreciation of using metrics to measure personal experiences. But, he said, the technique is important in determining psychological distress in patients.

“Although it is difficult to have certainty about the future level of interest in measurement-based care, if a recent past can be used as a predictor, the future is bright for evidenced-based treatments,” Dr. Maidenberg said.

A particular benefit for young patients

Dr. Fleisher said using measurement-based care has made treatment easier for his child and adolescent patients and their parents.

“It’s been awesome for parents to feel like this is not totally subjective, because it’s terrifying to consider having your child take medicine for anything related to the brain. So, measurement-based care is very assuring to parents,” he said.

“With teenagers, it’s more bricks for me to build a relationship with them,” he said. “They know that I care enough about them when I am handling their care in such a detailed way.”

If you want to book an appointment with a UCLA psychiatrist or learn more about how measurement-based care can help you, visit UCLA Health Psychiatry.