Kidney Stones

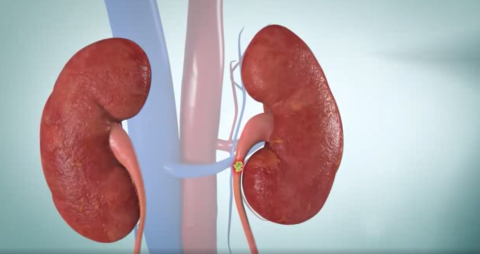

What are kidney stones?

Every year, more than a million patients see healthcare providers for kidney stones (also known as nephrolithiasis). Kidney stones are one of the most common causes for urgent care, emergency room, and primary care visits in the United States. Approximately one in eleven individuals develop kidney stones, with men at a higher risk than women. The rate of people affected by this disease is currently on the rise, attributed to the average diet, lifestyle, and increasing obesity rate of the U.S. population (PubMed).

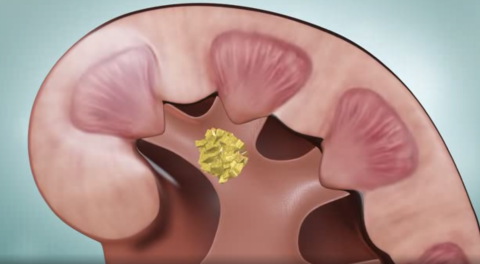

Kidney stones are hard masses created from a build-up of minerals and salts resulting from biochemical abnormalities in the blood and urine. These masses are caused by genetic, dietary, and environmental factors. Although small kidney stones can pass on their own, large kidney stones may cause extreme pain, severe infection, and kidney function decline. Evaluation by a nephrologist (a kidney specialist) can help prevent the recurrence of kidney stones.

What causes kidney stones?

Kidney stones result from an elevated concentration of electrolytes and chemicals in the urine or blood. Processes that increase the concentration of calcium, oxalate, and other chemicals in the urine to a critical point (called supersaturation) highly increase the risk of kidney stone formation. Once a stone forms, chemicals will continue to deposit on the initial stone causing the stone to grow.

Factors that increase the risk of developing kidney stones include:

- Gender: Men are more likely to develop a stone compared to women

- Race: White, non-Hispanic individuals are more likely to develop a stone

- Related Medical Conditions: obesity, urinary tract infection (UTI), gout

- Genetics and Family History

- Age: older individuals are more likely to develop a stone

- Dehydration

- Diets high in protein, sodium, and sugar (fructose)

- Excessive exercise

If you previously had a kidney stone, you are at an approximated 50% increase risk of having another stone within 5 to 7 years.

How do you recognize a kidney stone?

The classic symptom of a kidney stone is pain on the side (flank) of the body that radiates down to the groin. This pain can be severe, cramping, and constant. Some kidney stones are as small as a grain of sand while others are larger. In general, the larger the stone, the more noticeable the symptoms.

Symptoms include:

- Flank pain

- Additional vague pain or stomach discomfort that does not go away

- Persistent need to urinate

- Pain with urination

- Abnormal urination (urinating either more than usual or urinating a smaller amount)

- Urine that smells bad or looks cloudy

- Hematuria (blood in the urine)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fever

Chills

What are the most common types of kidney stones?

Kidney stones are the result of the build-up of electrolytes and chemicals in the urine.

The four main types of stones are:

- Calcium Oxalate: The most common type of kidney stone. Oxalate is a naturally occurring substance in fruits, vegetables, nuts, and chocolate. When bound with calcium, hard clumps of mineral can form. These crystals usually form when there is a high concentration of oxalate or too little urine in the body.

- Uric Acid: These stones can be caused by foods with high concentrations of natural purines, such as meats. High purine intake leads to a higher production of uric acid (also known as monosodium urate) which causes the urine to become acidic. If not enough water is consumed while the urine is highly acidic, the urine can become too concentrated making stones more likely to form.

- Struvite Stones: These stones are less common and are caused by an infection. During a bacterial infection, such as a urinary tract infection (UTI), ammonium levels rise turning urine, which is normally slightly acidic, to become alkaline. These stones are built up of ammonium, magnesium, and phosphate mineral which do not dissolve in alkaline urine. Struvite crystals can grow quickly and become quite large.

- Cystine Stones: These stones are rare and tend to be caused by genetics. They are commonly produced with patients who are homozygous for the recessive cystine transport gene causing a disorder called cystinuria causing elevated levels of cystine in the urine which make stones more likely to form.

How are kidney stones diagnosed?

Kidney stones are commonly diagnosed in the following ways:

- Medical history and physical examination

- Blood testing (may reveal elevated levels of calcium or uric acid in the urine)

- Imaging tests such as a CT scan, ultrasound, or KUB (kidney-ureter-bladder) x-ray. In some cases, an intravenous pyelogram (IVP), a type of x-ray taken after injecting a dye is required.

After the removal of the stone, your doctor will analyze it to determine the cause of the formation. Not everyone needs to see a doctor about kidney stones, but it is necessary in some cases, such as with young children and patients with only one kidney or recurrent stone formers.

If you had one stone, you are at an approximated 50% increased risk of having another stone within 5 to 7 years.

How are kidney stones treated?

Kidney stones are treated based on several factors including the severity of pain, the location of the stone, and the presence of infection. Most stones less than 5 mm in diameter are easily passed on their own while those that are larger than 10 mm require further treatment. Most patients can be treated at home while others require admission to the hospital. If a stone is too large to pass on its own, is extremely painful, or is obstructing, a surgical procedure or another procedural attempt to dislodge/break up the stone may be indicated. These procedures are performed by urologists who are surgeons of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder.

Most stones do not require an invasive procedure. You can pass a small stone by:

- Drinking as much as 2-3 liters of water a day to flush your kidneys

- Medication for pain and nausea

- Intravenous fluids

- Medical therapy to relax the muscles of the ureter

UCLA's Stone Treatment Center in Westwood, Santa Monica, and Santa Clarita facilities provide several surgical and medical treatment options for large stones that are unable to pass on their own. Their cutting edge operating rooms are equipped with the latest technology and are utilized by UCLA's fellowship trained urologists.

Extensive Therapy and Surgical Options include:

- Non-invasive shock wave lithotripsy (SWL)

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

- Ureteroscopy (URS)

- Pyelolithotomy

How do you prevent kidney stones?

- Drinking at least 2-3 liters of fluid per day

- Diets low in sodium, animal protein, and oxalates

- Diets rich in fruits, vegetables, and citrate

- Maintaining a healthy weight

- Moderating calcium intake

Please consult your healthcare provider before making any dietary changes.

Genetic Causes of Kidney Stones

It is estimated that 40% of patients with kidney stones are caused by inherited genetics. Listed below are a few rare genetic causes of kidney stones.

- Cystinuria: This rare condition affecting the kidneys causes an elevated level of cystine, an amino acid, to be excreted in the urine that make cystine stones more likely to form

- Hypocitraturia: Citrate naturally metabolizes kidney stones, but patients that inherit hypocitraturia have a decreased level of citrate in the urine, therefore, increasing the risk factor of harmful kidney stones developing

- Hypercalciuria: This genetic condition promotes elevated levels of calcium in the urine that increase the risk of developing calcium oxalate stones along with various other medical conditions.

- Enteric Hyperoxaluria: When there is an elevated level of oxalate excreted in the urine as a result of several intestinal diseases. This excess oxalate when combined with calcium can form calcium oxalate stones.

One of the major genetic causes of kidney stones is due to Primary Hyperoxaluria disease.

Primary Hyperoxaluria Disease

Overview of Disease

Primary Hyperoxaluria (PH) is a rare genetic disease of the liver that increases the level of oxalate in the urine. Oxalate is a product of metabolism and is found in certain types of food. This compound is toxic and greatly increases the risk of kidney stone formation.

There are three types of Primary Hyperoxaluria disease: type 1 (PH1), type 2 (PH2), and type 3 (PH3). PH1 is the most prevalent and severe form affecting 70-80% of PH patients which is approximately 4 individuals per million in the United States and Europe. Type 1 is currently treated with combined liver and kidney transplants while type 2 is a milder where kidney failure is not as apparent.

Early diagnosis and proper treatment of hyperoxaluria are essential to maintain the long-term health of your kidneys.

Causes of Primary Hyperoxaluria disease

PH is an inherited disease in which the liver does not create enough functional enzymes to prevent elevated levels of oxalate in the blood and urine. Since PH is a condition present from birth, kidney stones may form as early as during childhood or adolescence and may progress to kidney failure by adulthood if not properly treated.

In healthy individuals, glyoxylate in the body is metabolized by an AGT enzyme to produce glycine. Patients with PH1 do not produce enough AGT. Without AGT, glyoxylate converts into oxalate, therefore, increasing the body’s oxalate levels. An increased level of oxalate increases the risk of kidney stone formation that could lead to kidney failure. If oxalate is unable to be excreted from the kidneys through urine, it may deposit in vital organs such as the eyes, bones, skin, and heart. This is a condition called oxalosis.

Symptoms

Initial signs of primary hyperoxaluria disease are the manifestation of kidney stones. Common symptoms of kidneys stones include:

- Flank pain

- Additional vague pain or stomach discomfort that does not go away

- Persistent need to urinate

- Pain with urination

- Abnormal urination (urinating either more than usual or urinating a smaller amount)

- Urine that smells bad or looks cloudy

- Hematuria (blood in the urine)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fever

- Chills

Diagnosis

Primary hyperoxaluria disease can be diagnosed through various methods that include:

- Urine and Blood tests to measure oxalate levels

- Stone analysis to examine the composition of the stone

- X-ray, ultrasound, or computed tomography (CT) scan to locate kidney stones and calcium oxalate deposits

- DNA testing to investigate genetic causes

- Kidney biopsy to locate oxalate deposits in the kidney

- Echocardiogram to locate oxalate deposits in the heart

- Eye examination to locate oxalate deposits in the eyes

- Bone Marrow biopsy to locate oxalate deposits in the bone

- Liver Biopsy to determine enzyme deficiencies in rare cases that genetic testing does not indicate hyperoxaluria disease

Treatment

For patients with PH, currently the only curative treatment is a liver transplant, and if kidney failure is apparent, a dual liver/kidney transplant is required. However, treatments to reduce calcium oxalate formation can be effective in kidney stone management.

- Medications: Doses of vitamin B-12 and prescription phosphate and citrate can be effective in preventing the formation of calcium oxalate stones.

- High fluid intake to flush the kidneys

- Dietary Changes: Your doctor may recommend changes in your diet that may include limiting foods high in oxalate and salt and restricting animal proteins and processed sugars.

- Dialysis may be necessary if there is a significant decline in kidney function

Recently there have been significant advancements in PH1 treatment and a novel treatment is on the horizon. Lumasiran is an investigational, subcutaneously administered (under the skin) RNA interference (RNAi) therapeutic targeting hydroxyacid oxidase 1 (HAO1) gene in development for the treatment of primary hyperoxaluria type 1 (PH1). HAO1 encodes the glycolate oxidase (GO) enzyme. Thus, by silencing HAO1 and depleting the GO enzyme, lumasiran inhibits the production of oxalate – the metabolite that directly contributes to the pathophysiology of PH1. Lumasiran has received both U.S. and EU Orphan Drug Designations, a Breakthrough Therapy Designation, and pediatric rare disease designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Complications of Disease Progression

Although PH1 is a genetically inherited disease and patients may experience symptoms during childhood, many patients are not diagnosed immediately since kidney stones are not common in children. As a result, patients with PH1 may not be diagnosed until they are adults or presented with severe kidney disease. PH1 can progress and result in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in which the kidneys are unable to filter fluids and waste from the body. Oxalate buildup can also be deposited in the eyes, skin, heart, and nervous system which may cause blurred vision, ulcers, heart failure, bone fractures, and other complications.

Management of Diabetic Kidney Disease

Many kidney diseases have no cure. Therapeutics for kidney disease act to prevent or delay disease progression by managing symptoms and reducing complications. Diabetic Kidney Disease, with the underlying condition of diabetes mellitus, can contribute to worsening kidney function. However, breakthroughs in SGLT2 inhibitor class drugs and MRA-based therapeutics greatly contribute to the management of Diabetic Kidney Disease.

SGLT2 Inhibitors

What are SGLT2 Inhibitors?

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are a class of anti-hyperglycemic medication that is FDA approved. This class of drug was found to be beneficial to patients with type 2 diabetes as an alternative to insulin due to its novel mechanism. With numerous drug classes targeting type 2 diabetes, SGLT2 inhibitors work to manage blood sugar levels while protecting kidney function while also preventing cardiovascular complications.

SGLT 2 Inhibitors are also associated with a low risk of hypoglycemia, may lower body weight, blood pressure, and serum urate level, and also reduce relevant cardiovascular and renal adverse outcomes contributing to an attractive clinical drug profile

Common SGLT2 medications include:

- Canagliflozin (Invokana)

- Dapagliflozin (Farxiga)

- Empagliflozin (Jardiance)

- Ertugliflozin (Steglatro)

How do SGLT2 Inhibitors Work?

Function of SGLT 2 Protein

SGLT 2 proteins are found in the proximal convoluted tubule of the kidneys and are responsible for about 90% of glucose reabsorption, the transporting of glucose back into the bloodstream. These proteins are symporters that function through secondary active transport and reabsorb glucose using a sodium electrochemical gradient, which is dependent on the concentration of sodium. Renal glucose reabsorption is an important physiological process of the kidneys in maintaining blood glucose levels. This process allows the body to preserve energy to contribute to systemic metabolic function while minimizing energy substrate loss in the urine.

Diabetes and its Effect on Kidney Function

Diabetes and hyperglycemia (elevated blood glucose level) contribute to the worsening of kidney function. Patients with diabetes experience an enhanced glucose load to the proximal tubule of the kidney. The kidneys adapt to the increased glucose load by developing hyperplasia (increased cell reproduction leading to tissue growth) of the kidney tubule and hypertrophy (increased size of cells) of the proximal tubule. This adaption allows for an increase in SGLT 2 protein expression, therefore, having greater glucose reabsorption back into the blood. This adaptation is not adequate because it maintains hyperglycemia.

Another effect of this adaptation is the increase of sodium and fluid reabsorption which results in the reduced delivery of ions (sodium, potassium, and chloride) deeper into the kidney. The macula densa is an area deep in the kidney that consists of specialized cells which sense changes in ion concentration and react via the tubuloglomerular feedback loop to regulate the ion and fluid delivery to the distal (end) tubule. As the macula densa senses a decrease in ion concentration due to the increased expression of SGLT 2 proteins, nephron GFR (glomerular filtration rate) increases causing hyperfiltration. This occurs to as the kidneys try to maintain the equilibrium of ion and fluid balance.

Hyperfiltration is an abnormal increase in GFR (glomerular filtration rate) due to the enhanced level of fluid and ion delivery in the kidney system. This, in turn, increases the tubular transport of the kidneys for reabsorption. Tubular transport of the kidneys is an active process that requires oxygen consumption, therefore, hyperfiltration may lead to renal hypoxia and renal interstitial fibrosis. Hyperfiltration is a condition that leads to the progression of DKD (diabetic kidney disease) and CKD (chronic kidney disease).

Mechanism of SGLT 2 Inhibitors

SGLT 2 inhibitors work to decrease the level of blood glucose and therefore increase insulin sensitivity and uptake of glucose in the muscle cells. SGLT 2 inhibitors function to block SGLT 2 proteins, minimizing their glucose reabsorption function. Minimizing glucose reabsorption was shown to increase urinary glucose excretion, decrease gluconeogenesis, and improve insulin release from beta cells of the pancreas. This approach to diabetic management differs from other antidiabetic therapies with its insulin-independent mode of action. By reducing the extent of physical and metabolic burdens of hyperfiltration on the kidney, SGLT 2 inhibitors lessen renal damage in a diabetic environment. This effect contributes to the renoprotective attribute of this class of drug.

What is the significance of SGLT2 Medications of DKD?

In most cases, SGLT 2 Inhibitors are taken as an oral tablet and are used in addition to other diabetes medications. This class of medication is not for all patients with Diabetic Kidney Disease, especially those with severe kidney disease or on dialysis. Patients should consult their doctor before starting any medications or adopting lifestyle changes.

Advantages include:

- Alternative for insulin to manage diabetes

- Typically lowers HbA1c (reflection of blood glucose levels) by 0.5-1% after about 6 months of therapy

- Mild Weight Loss

- Preserves GFR and kidney function in the long term

- Associated diuretic and natriuretic

- Lowers blood pressure

- Preserve cardiovascular health

Disadvantages include:

- May induce very low blood pressure

- Increased urination

- Increased risk for urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Increased risk for yeast infection

- May lead to ketoacidosis

Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists

What are mineralocorticoids receptors?

In order to understand what mineralocorticoid receptors are, it’s important to define what a mineralocorticoid is. Mineralocorticoids are steroid hormones that play a role in the regulation of vital minerals needed for critical bodily processes. Aldosterone is an example of an important mineralocorticoid that is synthesized in the adrenal gland and regulates sodium and potassium transport in the distal convoluted tubules of the kidneys. Specifically, aldosterone regulates the epithelial sodium channels on the apical membrane of the distal convoluted cell. Aldosterone, however, has recently been found to also have extrarenal effects through stimulation of necrosis, fibrosis, and inflammation.

Thus, mineralocorticoid receptors are intracellular receptors that act as a nuclear transcription factor, a protein that binds to DNA to control the rate of transcription of genes. Upon binding of the mineralocorticoid to the receptor, the receptor produces rapid effects through secondary signaling mechanisms. Mineralocorticoids, such as cortisol and aldosterone, bind to the receptor with the same affinity but the aldosterone-MR complex is more stable and active than the cortisol-MR complex. These kinetics have helped scientists determine that increased aldosterone levels contribute greatly to increased MR activity and aldosterone became a target for many therapeutics. Aldosterone is stimulated by hyperkalemia, marked by high potassium serum levels, or hyponatremia, marked by low sodium serum levels. Aldosterone activates the MR and the MR increases the activity of proteins in kidney cells that transport sodium and potassium. The proteins keep sodium in the cell whilst removing potassium from the cell in order to increase sodium levels to homeostasis.

Abnormal increases in MR activity affects fluid, electrolyte, and hemodynamic homeostasis which can lead to:

- Necrosis

- Fibrosis

- Organ damage

- Hypertension

- Diabetes mellitus

- Chronic kidney disease

What are MRA's and how to MRA's treat diabetic kidney disease?

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) are drugs that block aldosterone from binding to the receptor. These therapeutics are a new treatment option for DKD patients with excessive aldosterone that is causing inflammation and a proliferative response due to increased MR activity. The MRA’s work to lower blood pressure and control extracellular volume homeostasis in patients by decreasing aldosterone’s effect on MR activity.

Traditionally, ACE inhibitors have been used to curb excess aldosterone, specifically in patients with cardiovascular problems. ACE inhibitors stop the production of angiotensin-II, an enzyme that produces aldosterone. However, this is not an effective treatment because aldosterone secretion is also stimulated by other sources such as hyperkalemia and atrial natriuretic peptide. Thus, researchers have focused on synthesizing a therapeutic that blocks aldosterone at a receptor level.

Clinical trials have shown that MRA plus ACEI ARB, therapeutics that block angiotensin-II, have been shown to significantly improve UAE and UACR in patients with DKD. A decrease in UAE and UACR is a marker for improved renal function. Additionally, combined therapy shows improved blood pressure control which results in reduced blood pressure to the glomeruli, an effect that correlates with renal improvement.

Current MRA Therapeutics

Spironolactone

Spironolactone was one of the first MRAs to be synthesized and has the molecular formula C24H32O4S. From its structure, we can see that spironolactone has the steroidal structure with three six-membered rings and one five-membered ring, making it a steroidal MRA. Spironolactone binds to the mineralocorticoid receptor in the same spot that aldosterone binds, making it a competitive inhibitor. The MRA binds with high affinity to the receptor but has low selectivity and fast dissociation which has led researchers to synthesize more advanced MRAs.

Spironolactone, being one of the oldest MRAs, has been tested in multiple clinical trials and has been shown to decrease albuminuria. For example, sixteen studies testing the effects of spironolactone on type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients show a 39% decrease in albuminuria over the course of 2-8 months. Additionally, experiments have shown that spironolactone inhibits the production of urinary MCP-1 and reduces oxidative stress for type 2 diabetic patients.

Eplerenone

Eplerenone is a derivative of spironolactone with a molecular formula C24H30O6 and has a very similar structure to spironolactone. Eplerenone, like spironolactone, has the steroidal structure and thus is classified as a steroid MRA. Differing from its predecessor, eplerenone has a lower affinity to the receptor but has a higher selectivity. This particular MRA binds to the MR and stabilizes the receptors inert conformation in order to inactivate the receptor.

Studies show that eplerenone significantly reduces blood pressure with a dose-dependent effect but was less effective than spironolactone. In one clinical trial, patients with diabetic kidney disease were given a dosage of 200 mg of eplerenone, 40 mg of enalapril, or a combination therapy of 200 mg eplerenone and 10 mg enalapril daily. Results indicated that there was a significant reduction of UACR independent of the reduction of blood pressure in patients with the combined therapy.

Finerenone

Finerenone is a third generation MRA that is non-steroidal. When looking at its structure, one can notice that it lacks the basic building block steroid and is very different from the previous two MRAs. Finenone, rather than binding to the substrate domain of the MR, induces a conformational change in the receptor. Additionally, finerenone is highly selective, highly potent, and more polar than the steroidal MRAs. This contributes to its effectiveness as its less likely to cause adverse events.

A Phase III clinical study on patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus indicated that treatment of finerenone resulted in lowered risk of kidney failure, decrease of eGFR by greater than 40% of baseline, and decrease in secondary outcome events such as death by cardiovascular disease. Moreover, a clinical study with 823 patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus used different doses of finerenone and results showed a dose-dependent reduction in albuminuria and that adverse events were similar to the placebo group.

Significance of MRA's for treating DKD

Although MRAs are a breakthrough therapeutic for the proliferative diabetic kidney disease, they can have adverse events that can limit its clinical use. Steroidal MRAs, specifically, can cause hyperkalemia and combined therapy of steroidal MRAs and ACE inhibitors have shown to increase hyperkalemia in some patients. This adverse event can be combated by undergoing heavy screening of patients to ensure that patients with history of hyperkalemia are not given MRA treatment and by monitoring other patients closely. In addition, spironolactone is nonselective and acts as an antagonist of androgen receptors and an agonist of progesterone receptors. This can cause side effects such as gynecomastia and menstrual irregularities. Moreover, steroidal MRAs are lipophilic and thus can cross the blood brain barrier. This can be dangerous due to the fact that most of the mineralocorticoid receptors in our body are concentrated in the hippocampus of the brain.

Although current data on new MRA’s like finerenone are limited in comparison to the older steroid MRAs, non-steroidal MRAs provide a solution to many of the adverse events stated above. Finerenone, specifically, has been shown to significantly decrease the progression of kidney disease by 18% over a median of 2.6 years compared to current care. Additionally, finerenone has higher potency and less hyperkalemic effects than the steroidal MRAs. Finerenone, being more polar and less lipophilic, has a greater tissue-specificity. Clinical studies have shown that f 5 or 10 mg of finerenone daily has the same benefits as 20 - 25 mg of spironolactone with lower incidences of adverse events.

Next Steps for Broad Clinical Use of MRA's

- Need to find an MRA that has a tissue and function-specific mode of action

- Need to further research effects of MRA's on DKD patients specifically

- Focus more attention on non-steroidal MRA's and conduct more clinical trails with Finerenone to collect more data

Disclaimer: The information on this website is for informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as a substitute for consultation, diagnosis, or medical treatment from a qualified healthcare provider. Readers should consult with their physician or healthcare provider before making any changes. The UCLA Health System cannot guarantee the accuracy of such information.

Contributors:

- Medical Director of the UCLA Kidney Stone Program | Ray Reza Goshtaseb, MD, FASN

- Member of the Bruin Beans Health Club | Josh Ooka, UCLA Undergrad

References:

- Dojki FK, Bakris G. Nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid antagonists in diabetic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017 Sep;26(5):368-374. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000340. PMID: 28771453.

- Edvardsson, Vidar O, et al. “Hereditary Causes of Kidney Stones and Chronic Kidney Disease.” Pediatric Nephrology (Berlin, Germany), U.S. National Library of Medicine, 20 Jan. 2013, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23334384/.

- Frimodt-Møller, Mariea; Persson, Frederika; Rossing, Petera,b Mitigating risk of aldosterone in diabetic kidney disease, Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension: January 2020 - Volume 29 - Issue 1 - p 145-151 doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000557

- “Hyperoxaluria and Oxalosis.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 16 Mar. 2019, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hyperoxaluria/symptoms-causes/syc-20352254.

- “Kidney Stones.” National Kidney Foundation, 2 Oct. 2020, www.kidney.org/atoz/content/kidneystones.

- Kolkhof, Petera; Nowack, Christinab; Eitner, Franka Nonsteroidal antagonists of the mineralocorticoid receptor, Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension: September 2015 - Volume 24 - Issue 5 - p 417-424 doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000147

- Kumbhani, D. J. (2021, August 28). Finerenone in reducing kidney failure and disease progression in diabetic kidney disease. American College of Cardiology. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- Nespoux, Josselin, and Volker Vallon. “SGLT2 Inhibition and Kidney Protection.” Clinical Science, vol. 132, no. 12,

2018, pp. 1329–1339. - New Drug, positive results. how will it benefit people with diabetic kidney disease? National Kidney Foundation. (2020, November 23). Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- Perkovic, V. (n.d.). Treatment of Diabetic Kidney Disease. UpToDate. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- Samy I. McFarlane, James R. Sowers, Aldosterone Function in Diabetes Mellitus: Effects on Cardiovascular and Renal Disease, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 88, Issue 2, 1 February 2003, Pages 516–523.

- Scales, Charles D, et al. “Prevalence of Kidney Stones in the United States.” European Urology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 31 Mar. 2012, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22498635/.

- Sica D. A. (2015). Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists for Treatment of Hypertension and Heart Failure. Methodist DeBakey cardiovascular journal, 11(4), 235–239.

- Sun, L. J., Sun, Y. N., Shan, J. P., & Jiang, G. R. (2017). Effects of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists on the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Journal of diabetes investigation, 8(4), 609–618.

- “Understanding Primary Hyperoxaluria-Symptoms and Causes: Alnylam®.” Alnylam, www.alnylam.com/patients/primary-hyperoxaluria/.

- U.S Food and Drug Administration. “Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors.” U.S. Food and Drug

Administration, FDA, 20 Aug. 2018, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/sodium-glucose-cotransporte

r-2-sglt2-inhibitors. - Vallon, Volker. “The Proximal Tubule in the Pathophysiology of the Diabetic Kidney.” American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, vol. 300, no. 5, 2011.

- VodošekHojs,N.;Bevc,S.; Ekart, R.; Piko, N.; Petreski, T.; Hojs, R. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 561.

For additional information, please contact our UCLA CORE Kidney Stone Program experts

Ray Reza Goshtaseb MD, FASN

Medical Director | Kidney Stone Center

Clinical Instructor

UCLA CORE Kidney Program

Division of Nephrology | Department of Medicine

DGSOM and UCLA Health

1245 16th Street Ste. #307 Santa Monica, CA 900404

Ph: 310-481-4228

Matthew D. Dunn, MD

Associate Clinical Professor of Urology

Division Chief of Endourology and Stone Disease

1260 15th Stre. #1200 Santa Monica, CA 90404

Ph: 310-794-7700

Kymora B. Scotland MD, PhD

Assistant Professor

Department of Urology

UCLA