Achalasia

Find Your Care

We work as a team to provide outstanding esophageal care. Call 833-373-7674 to connect with a specialist at the UCLA Robert G. Kardashian Center for Esophageal Health.

What is achalasia?

Achalasia is a disease of the nerve and muscle function of the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter (LES). It is also sometimes called cardiospasm, referring to tightness of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ, aka "cardia"). The normal motility function of the esophagus is to transfer the bolus of food from the throat in a coordinated fashion through the esophagus in the chest toward the abdomen. The LES then relaxes to allow the food to enter the stomach. In achalasia and other motility disorders of the esophagus, this highly coordinated neuromuscular activity is disrupted and results in characteristic symptoms.

Achalasia (meaning "no relaxation") is defined by 1) failure of normal peristalsis (muscular contraction or motility) of the esophagus and 2) failure of the LES to relax. The diagnosis is made after exclusion of another cause, such as a mechanical obstruction (for example, a tumor of the GEJ). There are other motility disorders of the esophagus such as diffuse esophageal spasm, spastic LES, nutcracker esophagus, jackhammer esophagus, etc. that are distinct from achalasia but may have similar symptoms and may occasionally be treated in a similar way. Your doctor can help guide you if these other disorders of the esophagus are relevant to you.

What causes achalasia?

The exact causes of achalasia and other motility disorders of the esophagus are not known for certain. It is thought that the disease may be the result of the body's own immune system mistakenly attacking the nerves that regulate muscle function of the esophagus and LES. This autoimmune response may be a result of an inappropriate reaction to an infection, such as a virus, but theories have not yet been substantiated. Typically, by the time the symptoms of achalasia have manifested, the initial insult is no longer present or is undetectable.

What are the symptoms of achalasia?

The main symptom of achalasia is dysphagia, meaning difficulty in swallowing. This may manifest as a food sticking sensation or feeling of a delay of food passage in the throat, chest, or upper abdomen. This may start with, or be more severe with, certain foods or pills, but typically progresses to include most or all oral intake including liquids and solids. This happens as a result of the inability of what is swallowed to pass normally through the esophagus and GEJ to enter the stomach. Often undigested food or fluid may sit and become stagnant in the esophagus. Occasionally, this may "ferment" and cause symptoms reminiscent of heartburn. There may be associated regurgitation or non-projectile vomiting of undigested food that has sat in the esophagus and is unable to empty into the stomach. Occasionally this may be severe enough for the regurgitated food to enter the lungs and cause aspiration pneumonia. Because of the decrease in nutrients reaching the intestines, weight loss may eventually become a major feature. In some patients, there is chest pain as a result of the abnormal peristalsis or spasm of the esophagus. In different patients and at different times, these various symptoms may be present occasionally, daily, or with every meal (or not at all). Typically, however, the disease is progressive over a period of time and symptoms worsen. These symptoms can be quantified by a standardized system called the Eckardt score; a score of zero indicates no symptoms and a score of 8-12 indicates severe symptoms.

How is achalasia diagnosed?

The cardinal symptoms of achalasia (dysphagia, regurgitation, weight loss, chest pain) are not specific to achalasia. Specific testing is needed to differentiate achalasia from other disorders including acid reflux (gastroesophageal reflux, GERD), tumors or cancers, benign strictures, inflammatory or allergic conditions, infections, and other diseases. Tests to confirm the diagnosis of achalasia include upper endoscopy (aka EGD and sometimes including endoscopic ultrasound - EUS), x-rays (including esophagram and/or CT scans), and high-resolution manometry. In general, although other tests can suggest the presence of achalasia, manometry is needed to confirm the diagnosis with accuracy.

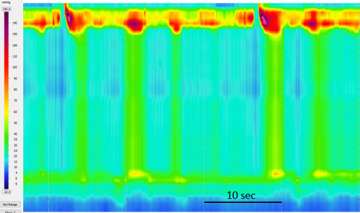

What is high-resolution manometry?

Manometry means "measurement of pressure." This is performed by passing a thin catheter through the nose into the esophagus and stomach and recording pressure changes during swallowing. Since the normal neuromuscular function of the esophagus and LES is disrupted in a characteristic way, the pattern of abnormalities in the pressure readings can help diagnose achalasia or other motility disorders of the esophagus. High-resolution manometry uses a more sophisticated catheter that has more sensitivity for diagnosing achalasia and differentiating it from other disorders. Significantly, high-resolution manometry can be used to subtype achalasia. Determining the exact nature of the motility disturbance and/or subtyping achalasia has important implications for treatment and prognosis.

What do the subtypes of achalasia mean?

There are three currently identified subtypes of achalasia and they are important because they can help predict the response to treatment and may help select what kind of treatment is most appropriate. All three are characterized by failure of the LES to relax and abnormal peristalsis of the esophageal body; they differ in the way the peristalsis of the esophagus is abnormal. They each have specific patterns that can be diagnosed with high-resolution manometry. Your doctor can give you details about your subtype of achalasia. One type is not necessarily "worse" or "better" than the others. Type III achalasia is special because it involves spasm of the esophageal body. Patients with type III achalasia may have chest pain as a significant symptom and need special attention to the esophagus when a treatment modality is selected.

What are the treatment options for achalasia?

There is no known cure for achalasia. All of the treatment options are palliative, meaning they strive to reduce or eliminate the major symptoms of achalasia and to improve quality of life. These treatment options aim to relax or disrupt the muscle of the esophagus and allow food to enter the stomach more easily.

- Medications (such as calcium channel blockers or nitrates) have been used to treat the symptoms of achalasia; they are often have intolerable side effects and may not be definitive or durably effective and are thus rarely used.

- Botulinum toxin (BoTox) injected into the muscle of the esophagus and GEJ with endoscopic guidance works by paralyzing the muscle and allowing relaxation. Although it is easy to perform and can be initially effective in relieving symptoms, the effects are temporary (typically on the order of weeks to months) and repeated injections lose efficacy. Furthermore, repeated injections can cause inflammation and scarring that can make more definitive treatments difficult or risky. As such, botulinum toxin should only be used for selected cases.

- Dilation can be used to stretch and disrupt the muscle of the GEJ and can improve swallowing. There are two types of dilation. Small caliber dilation (typically less than or equal to 20 mm in diameter and performed with either balloons or with specially designed dilation tubes) is commonly used to treat narrowing or scarring (aka strictures) throughout the GI tract. These modalities of dilation are not effective or only temporarily effective (days or weeks at most) for achalasia because the muscle is not disrupted completely. On the other hand, larger caliber dilation specifically designed for achalasia is performed with specially designed rigid, non-compliant balloons typically of diameters 30 mm and greater. This so-called "pneumatic dilation" effectively ruptures the spastic muscle of the LES and allows for improvement in swallowing. Although pneumatic dilation is an effective means of treatment and may be appropriate for many patients, it has some disadvantages. Typically several sessions are required to achieve adequate symptom relief and there may be a need for ongoing episodic "maintenance" dilation if symptoms recur. There is also an up to 4% risk of esophageal perforation that may require emergency surgery. Despite these disadvantages, it is a quick and relatively easy to perform outpatient procedure when performed by an expert endoscopist and may be appropriate for some patients.

- It is thought that the most effective and durable treatment for achalasia is cutting the muscle; this is called myotomy. This can be accomplished surgically (referred to as Heller myotomy) or endoscopically (referred to as Per-oral endoscopic myotomy or POEM). POEM is offered only at a few specialized centers around the country and we are excited to be able to offer this promising option to our patients.

- In end-stage or severe cases, the above treatment modalities may not be effective. In these extreme cases, the treatment may involve esophagectomy (surgical removal of the esophagus) and/or feeding tube placement. These measures are rarely necessary for most patients with achalasia.

What is a heller myotomy?

Heller myotomy is a well-established surgical procedure to treat achalasia that is usually performed laparoscopically (a few small incisions in the abdomen). The surgeon finds the GEJ and cuts the abnormal muscle spanning part of the upper stomach, the LES, and the lower esophagus. This is often accompanied with an antireflux procedure to partially reinforce the valve that has been disrupted at the GEJ. In most parts of the US, this surgery is considered the standard treatment of achalasia.

What is POEM and how is it performed?

POEM stands for "Per-oral endoscopic myotomy" and means cutting the muscle through the mouth with an endoscope. It is an incision-less endoscopic procedure that aims to recreate the Heller myotomy in a less invasive way. It follows similar surgical principles but is able to accomplish the myotomy less invasively. POEM was first described in 2010 in Japan and has since expanded worldwide to be performed in thousands of patients with excellent efficacy and safety.

The procedure depends on recognition and utilization of the layers of the esophagus. These layers can be separated from each other like the layers of an onion. The inner layer is called the mucosa (the layer that touches the food). The outer layer is the muscle layer and is the target layer for the myotomy. The layer between the mucosa and muscle is the submucosa, which is a thin layer of connective tissue that is expanded with injection of a fluid to form a working space (aka "submucosal tunnel").

The procedure is performed under general anesthesia in the hospital using a standard upper endoscope. After examination and cleansing of the esophagus and determining the appropriate measurements and landmarks, a point in the esophagus is selected and injected with a fluid solution to expand the submucosa. An incision (about 2 centimeters or 1 inch long) is made in the mucosa to serve as the entry point and the endoscope is maneuvered into the submucosal layer. Further injection of fluid in the submucosa followed by careful cutting of the submucosal fibers (dissection) allows for stepwise tunneling of the endoscope down the esophagus within the submucosal layer. This is continued through the GEJ and into the first few centimeters of the stomach. When this step is completed, a submucosal tunnel has been created that is bordered on one side by the intact mucosal layer and by the muscle layer on the other. The mucosal incision from the beginning of the procedure is the entry point to the submucosal tunnel. During the dissection, blood vessels are cauterized to prevent or treat bleeding as necessary (hemostasis). Once an adequate submucosal tunnel has been created, the first cuts of the muscle are performed. This myotomy is extended down the esophagus, the LES, and into the upper stomach (cardia). The typical length of myotomy is around 10 cm, though this may be shorter or longer as is necessary on a case-by-case basis. When the myotomy is deemed to be adequate (by a variety of methods), the mucosal incision that served as the entry point is sealed (with clips or sutures). In some cases, during the procedure, there is escape of gas into the abdominal cavity that requires decompression with a small caliber needle inserted through the abdominal wall to act as an escape mechanism for the gas that is insufflated during the procedure. This step is possibly necessary in up to 40% of cases. At the conclusion of the procedure, the needle is removed without consequence. The procedure is then completed and the patient is taken to recovery.

Watch video of the POEM procedure below.

Who is eligible for POEM?

In general, anyone who is eligible for a Heller myotomy is probably eligible for POEM. In some cases, POEM may be the preferred method over other treatment options. The indications for POEM include all types of achalasia. POEM may also be appropriate for other motility disorders of the esophagus (such as diffuse spasm, jackhammer esophagus, or other conditions). POEM may be offered for patients that have failed or have recurrent symptoms after Heller myotomy. Age is usually not an issue in the absence of major medical conditions; POEM has been performed in the pediatric population and in the elderly.

Some patients may not be eligible for POEM. These include patients with:

- Significant heart or lung conditions or other illnesses that make general anesthesia unsafe;

- Specific manifestations of liver disease or cirrhosis;

- Problems with normal clotting of blood - this may be due to medications (i.e. blood thinners that cannot be held), or may be due to an illness;

- Certain prior endoscopic therapies of the esophagus (for example ablation of Barrett's esophagus or resection of tumors);

- Radiation exposure to the esophagus or chest;

- Other conditions that may make POEM unsafe, ineffective or inadvisable that your doctor can discuss with you.

What are the advantages of POEM over other treatment options?

POEM is exciting for patients with achalasia and other motility disorders of the esophagus because it has potential significant advantages over other options.

For some disorders of the esophagus, POEM may be the best treatment option because it allows precise tailoring of the myotomy length in the esophagus as much as is needed to alleviate spasm and give a better chance at symptoms resolution. This is a distinct advantage over traditional laparoscopic surgery where the length of esophagus that can be cut in the chest is limited by the approach from the abdomen. Previously, this was overcome by a thoracic (chest surgery) approach to the myotomy, but this is felt to be more invasive and carry more potential side effects. Specific diseases that are probably best treated with POEM include type III achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, nutcracker esophagus, and jackhammer esophagus. In these disorders, the esophageal myotomy length can be tailored to treat the spastic segment as determined by high-resolution manometry.

POEM has a special advantage in cases of prior Heller myotomy. A minority of patients with achalasia will have either a failure of improvement or a recurrence of symptoms after Heller myotomy. Repeat surgical (Heller) myotomy is considered more difficult and higher risk, but POEM appears to offer an alternative to salvage these cases with a favorable efficacy and safety profile.

Besides these special disease entities, POEM appears to be equivalent or slightly better than traditional Heller myotomy for type I and II achalasia. There are currently no published head-to-head studies comparing POEM to Heller myotomy, but anecdotal and indirect evidence appears to show that POEM offers shorter hospital stay, less pain, and quicker return to usual activities. In some patients with difficult anatomy (such as obese or prior surgeries), POEM may be easier and safer to perform.

What are the potential adverse events or complications?

It is estimated that adverse events happen in less than 1-2% of patients undergoing POEM. These complications vary in severity and are similar to the types of complications that can happen with surgery. They include bleeding, infection, leaks or perforation, arrhythmias or other heart problems, fluid or air trapped in or around the heart or lungs, aspiration pneumonia, and reactions or problems with anesthesia. These complications may be mild or severe and result in longer or additional hospital stay and/or additional procedures or surgeries to address the problem. In general, these complications are very rare and POEM has an excellent safety record. There may be minor throat, chest, or abdominal pain after the procedure that can be expected but is usually easily controlled and lasts only a few days.

What about reflux after POEM?

The major new symptom after any myotomy, including POEM, is potential reflux (GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease). The normal LES acts as part of the body's normal anti-reflux mechanism. When the LES and surrounding muscles are cut to treat achalasia, reflux can result. The incidence of reflux after myotomy is up to 30-40% if reflux is defined by measurement of abnormal acid exposure by a pH probe; roughly one-half of these patients (15-20% of total patients) will have symptoms of reflux and the other half will have silent reflux. Most patients (60-70%) will not have detectable or significant reflux. Though controversial, it appears that the total rate of reflux is the same for POEM and Heller myotomy. Whether symptoms are present or not, reflux should be treated, usually with medications (proton pump inhibitors, PPI). Our protocol is to discharge all patients after POEM on PPI for a few months. After the esophagus has had a chance to heal and you are back to usual activity and diet, testing is performed to determine if PPI can be discontinued. It is important that everyone continue PPI during this initial period after POEM whether or not they feel reflux or heartburn.

What is the preparation before the POEM procedure?

- After your doctor has diagnosed achalasia and determined that you are eligible for POEM, a preoperative evaluation may be recommended. This will allow a doctor (such as an internist, cardiologist, pulmonologist, or anesthesiologist) to determine that it is safe for you to undergo general anesthesia or if additional testing (such as stress testing to detect silent heart disease) is needed.

- A list of your medications (including prescription, over the counter, and herbals or supplements) will be reviewed and medications that need to be stopped or temporarily held (such as blood thinners) will be advised.

- You will be asked to restrict your diet to liquids only for 72 hours prior to the procedure.

- You will be asked to take nothing by mouth after midnight the night before your procedure.

- You may be prescribed a liquid antifungal medication (such as nystatin) as a preventative measure to be taken for 5 days prior to the procedure.

What happens after the POEM procedure?

After the procedure you are taken to the recovery room where you are monitored for post anesthesia care. When you are stable from anesthesia, you are admitted to an overnight observation bed. Typically, patients post-POEM can expect to spend the night in the hospital following the procedure and then go home the following afternoon. During the day and night immediately following the procedure you will be kept strictly nothing by mouth (NPO: this means no food, drink, pills, or anything!). You will be observed for any complications and given medications for nausea and pain as needed. You will be given certain standard medications: this includes intravenous fluids for hydration, preventative antibiotics, and around the clock (whether you think you need it or not) anti-nausea medications to prevent vomiting or retching that could disrupt the site of the POEM.

The next morning, if there are no concerns, an esophagram (x-ray of the esophagus taken after swallowing a special dye) is performed to exclude a leak. If the esophagram shows no leak, you are given liquids and then a soft diet and then discharged from the hospital if you are able to eat and drink without pain. You are discharged with a few days of antibiotics and a prescription for PPI to prevent acid exposure of the esophagus (whether you feel reflux or not).

Your diet is restricted to soft or blenderized food for two weeks after discharge. This basically includes all food that you can swallow with minimal or no chewing. These are foods with consistency similar to smoothies, milkshakes, mashed potatoes, pudding, ice cream, soup, pureed vegetables, etc. The purpose of this is to introduce food gently into the esophagus so that it has a chance to heal. There have been rare severe complications reported when patients have not complied with the dietary instructions. After two weeks, you can slowly introduce regular food to your diet as tolerated. Download post-POEM diet instructions and recipes.

What is the expected follow-up after recovery from POEM?

A few months after your procedure, the post-procedural evaluation will start with pH testing to determine if you have acid reflux. You will be asked to stop your PPI for seven days and then an upper endoscopy will be performed. The esophagus will be inspected for signs of reflux and a small pH-sensing capsule (Bravo probe) will be clipped to the esophagus to measure acid exposure and relay that information for 48 hours to a small recorder that you carry with you. The probe will pass through your system spontaneously and the recorded data will be analyzed to determine if you have significant reflux. If you have symptoms of reflux or if the pH study is positive for reflux, you will be asked to resume your PPI. Your doctor can then discuss treatment options for reflux as appropriate.

Often, high-resolution manometry and esophagram are also repeated a few months after POEM to evaluate the efficacy of the procedure objectively and to serve as reference point in the unlikely event that there are recurrent symptoms in the future.

Though there are no firm guidelines or rules for patients with achalasia, your doctor may discuss occasional upper endoscopy as a screening or monitoring tool over the years after your POEM.

What are the expected outcomes after POEM?

Current studies of POEM for achalasia have indicated a >90% favorable response with normalization or near normalization of swallowing symptoms (post-POEM Eckardt scores typically are 0-1). For patients with non-achalasia spastic disorders of the esophagus (such as diffuse spasm or jackhammer esophagus), the outcomes are slightly less favorable (~80% response) but are much better than other treatment options. Because this is a new procedure, there is limited long-term data to know what the durability of the response is, but existing data suggest that the vast majority (>80%) of patients will maintain their response at least after 2 years (probably longer than that, but we don't yet have data to know for sure). If there are recurrent or residual symptoms after POEM, esophageal testing may be performed to determine what the problem is, and potentially additional therapy may be offered.

Watch videos on achalasia

Is it heartburn, GERD, achalasia or something else?

Alireza Sedarat, MD

Diagnosis and management of achalasia: Perspectives from a surgeon and gastroenterologist

Jane Yanagawa, MD and Alireza Sedarat, MD